Context of a transcription: African Ancestors in the first book of deaths

Back in 2006, while researching mundillo (lacemaking) in Moca, I was also learning more about a shared family history that ultimately led me to explore enslaved ancestors, African and Indigenous ancestors. Their strength and perseverance in the face of difficult situations inspires. As Daina Ramey Berry so eloquently writes in The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation (Beacon Press, 2017), we can recognize their soul value, and this goes beyond the missing surnames and identities that enslavement sought to steal away.

That September, I was able to transcribe some church entries from Nuestra Señora de la Monserrate for a small group of cousins and myself that coalesced into Sociedad Ancestros Mocanos. Sociedad Ancestros Mocanos, which I established on Yahoo! Groups, was where we asked each other questions and shared research findings and transcriptions. This process goes much faster today.

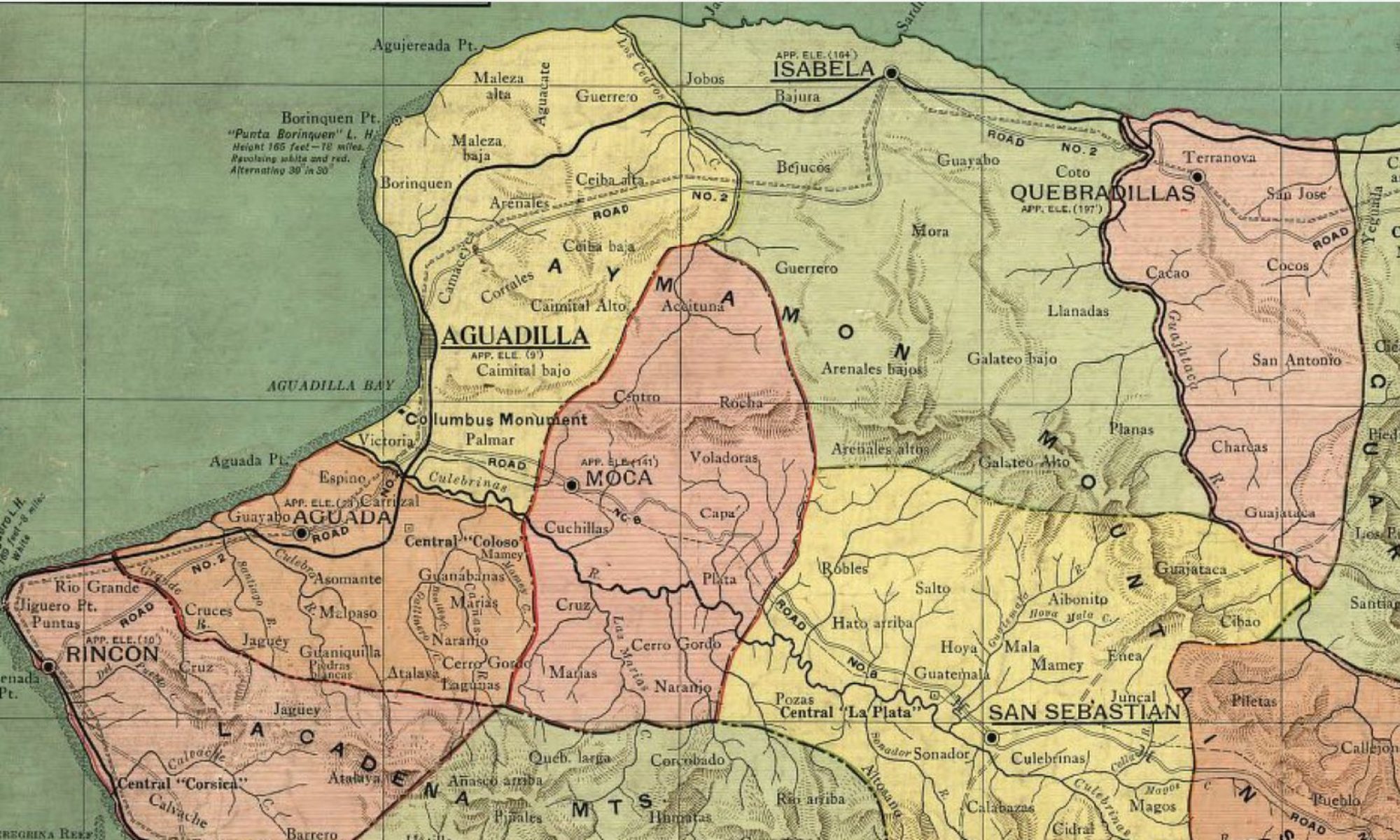

Initially, the census records and civil registration on microfilm were available at the local Family History Center, and we began to piece together trees that overlapped, merged and diverged across NW Puerto Rico and beyond. However, records from Moca such as the Libros de Bautismos, Defunciones y Matrimonios, like some parishes on the island, were not part of the LDS’ microfilm project of the 1980s-1990s. Because of that, any transcriptions obtained during trips were particularly of interest, and often held clues for moving another generation back in time. One of the things that we began to notice were the interconnections our families had, the oral histories, the fact of how an economy based on sugar also tied us to Africa, to the earlier history of colonization and Indian slavery, interrupted by myriad degrees of freedom both before and after slavery ended.

In Moca, I was fortunate to stay within the Pueblo, just blocks away from the building that dominates the center of town, Iglesia de Nuestra Senora de la Monserrate, built in 1853. The church had volumes of parish records in a small office building at the rear of the church, built atop a hillock at the center of Barrio Pueblo, occupying one side of the rectangular plaza.

Between 1 and 4 in the afternoon the office was open, and I brought my letter of approval from the Arzobispado de Mayaguez granting me permission to consult the volumes for genealogical research. I requested the first volume of Defunciones that begins in November 1852 and took the oversized book to a pupils seat, balanced it on the tiny desk and began to copy entries onto paper with a pencil.

Time was short, and I rapidly transcribed entries from surnames familiar from my research and shared with members of SAMocanos. I also noticed names of the enslaved among my entries and included them on my list, hoping to find connections later on. Now with DNA there is more chance to link to these ancestors, and hopefully, break down some brick walls.

A brief list of deaths, 1852-1859: Say Their Names

What follows are records for twelve people who were enslaved and who died between 1852-1859. Also listed are the names of an additional six persons who were their parents, along with several enslavers. These bits of secondary evidence, based on original records remain precious over time, as they both tie us to the place and to the ancestors in them. In some cases they are the only record available, some not digitized even into the present, so that the reliance on a transcription becomes almost a point of faith, yet can contain errors. In some cases, a transcription is often all that remains, and questions about who and what was in the original record are moot when these are no longer extant.

Among the names are Maria de las Nieves and Juana, who both survived the Middle Passage only to die age 48 and 53 during years of epidemics that took many lives. However, the parish record does not say why they passed. There may be accounts elsewhere listing those taken by epidemics. Also in the records is Juana Cristiana, a two year old child who was enslaved, as was her mother, and parish records reveal her parents married in the Catholic church. This did not change the fact they were in bondage, subject to sale or if they were able, to self purchase and thereby gain freedom before 1873. A very real fear was being sold or taken to another plantation in Cuba, where the scale of enslavement and sugar processing was ten times that of Puerto Rico, and slavery did not end until 1886.

Beyond those named, i’ve compiled a list of the parents mentioned largely mothers, whose names may appear in other additional documentary sources, such as notarial documents or for instance, be mentioned in the 1849 Censo de Altas y Bajas for Moca (in Hereditas and on the PReb.com site), or perhaps in other SPG publications, the 1830 Censo de Isabela or 1874 Censo de Lares among others. Another short list below is for the enslavers, under whose names the information on those listed, was entered into parish and municipal documents.

After freedom, surnames can follow those of the initial enslaver, or take on different surnames as relationships change or are revealed upon death or marriage. Please feel free to contact me should you find a connection.

The List of Ancestors

Discover more from Latino Genealogy & Beyond

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excellent post, Ellen! The Ancestors thank you!

Renate

Thanks so much Renate! I hope they do!

Ellen

I think those are my family. On my grandfathers genealogy information. We have Acevedo & Nieves from Moca Puerto Rico. The names matched my grandfathers information. Thank you so much I’m in awe. Thank you 🙏🏽

So glad you found the information! Thanks for reading Lisa!

Se le erizan los pelos y nos abre la mente…gracias.

I know many people,friends of mine, with Lazalles and Pellot’s last names in Moca,. But also Balaguer, Laguerre, Buldong, Abrew, all african slaves descendants,Their ancestors adopted their owners last name when they gained their freedom in 1873. But I don’t see those last name in your list. ,

..

Thanks for your comment Ariel, i’ve only transcribed a certain number of the cedulas de esclavos as v3 of the Registro de Esclavos is missing. I have come across Laguerre and Abreu in my transcriptions. I plan to submit the article to Hereditas later this month.

not only am i looking into my ancestors but march 25 is my birthday <3

Hola, Thank you for such rich information about PR’s past. My great-great grandmother Dominga Lasalle was born in Moca and according to Ancestry.com her mother was a slave there her name was Maria Juana Lasalle. How did you get permission to view the records at the Moca church? What other information have you found? Thank you so much. I appreciate what you are doing.👍👍

Hola Eirisa, thanks so much!! You’re so welcome. Which record did you happen to find? I’m not sure what the situation is with obtaining records after the storm. I was at the church’s archive way back in 2006, when I transcribed whatever I could from a couple of volumes. I hope they will be digitized eventually. The other information is an article on the missing volume of the 1872 Slave Register for the NW, and I transcribed Caja 4 of the original cedulas, which would have gone into the 1872 volume; this I hope to finally get to the SPG for an upcoming issue of Hereditas. Please let me know what years and location you have for Maria Juana Lassalle and her daughter, your GGM, Dominga Lassalle, I can check the transcription.

You’re so welcome Eirisa! I’m about to publish a list of people from the cedulas of 1870 on this blog, and have an article submitted on the context and history of the missing volume of the Registro de Esclavos. Perhaps your ancestor is in there. In order to get information from the archives of the Iglesia Monserrate, you need to ask for permission from the Arzobispado de Mayaguez. Notary records are the other resource that contain information on ancestors.

My grandparents were from Moca. Lasalle and Sanchez. My grandfather was very dark and grandmother was pale white. They moved to Aguadilla in the early to mid 1900’s.

Faustino,

Would they happen to be Isaac Lassalle Ramos (1893-1979) and Maria Sanchez Gonzalez? I’ve traced out parts of the Lassalle tree, am happy to share more information if you don’t already have it.

Ellen

This is very interesting to me. My family are LaSalles from Quebradillas. My great grandfather was dark skinned named Juan. Are they any other resources I can study or get my hands on. This has been very helpful. Thank you so much for posting this.

You’re welcome Daniel! Was your GGF Juan Lasalle (1891-1939) of Barrio Cocos? If so, I have traced his line back, but have not yet seen mention of enslavement. Understanding the local history helps, such as the books in the Notas de su historia series from 1983. The surviving records for each municipality can vary and some of these earlier documents are on FamilySearch, and the ADNPR.net. Before 1823, Quebradillas was part of Camuy.

Thank you for sharing.. we found out through ancestry.com about our GGM Juana Pellot. She was born to a slave named Florentina Pellot, my GGGM.

I wish I could find out more about them.

Sad to know our family were once slaves.. yet as bittersweet as it is, I’ve found a sense of clarity knowing where we came from. Knowing our roots, helped me understand why my siblings and I all had different features although we had the same parents. Some of us had very curly hair and olive skin. Then some of us had straight hair just a little wavy and light skin. Yet we all have some strong features. Beautiful as we all are different. I always scratched my head trying to find out why we look different. I hope I can find out more about them. Definitely greatful for your post. Is it possible, you might of came across the name Florentina Pellot? Or Juana Pellot?

You’re so welcome Lizzette – there is more information on the Pellots in my article, The Missing Registro de Esclavos for NW PR. also know that you have family, because Florentina had ten children, and there are many descendants . The 1870 cedulas for her and for Juana are on on FamilySearch:

Florentina’s cedula is here: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSK3-Z3SP-R?i=502&cat=612874

There’s Juana Gracia: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSK3-Z3D8-X?i=483&cat=612874

So many histories to excavate and tell

Thank you!! That was so helpful. I am very greatful for the information you’ve shared. I excitingly look forward to sharing with my family. Can’t imagine living life and not speaking of them or acknowledging their existence, When I and mine, are a magnificent part of them. Thank you so very much for what you do and have done.

It is said; “know where you come from, so you know where you are going”.

This has given me a reason to search my dads side of the family as well. To have facts v speculative stories from our family ( who mean well ) clarifies a lot. Thanks a million!

Hi there! Do you have any more information about Maria de las Nieves? I’ve traced my family back to the Nieves and Acevedos in that region at that time and would love to know more (I’m prepared for stories that are not flattering to my ancestors but hope to honor Maria by learning the story anyway!). Either way thank you for this it was incredible to find.

Thanks Christina! Ok, which Maria de las Nieves? There are a few of them, as with the Acevedo- so the where and when is key- in order to find the branches that connect. Given the endogamy (i.e. cousin marriages) of these families, you may wind up matching me as well! I have a Facebook group, Sociedad Ancestros Mocanos, which you can feel free to join and ask questions.

I have been able to find via internet info regarding distant Moca relatives, Manuel and Maria Andrea, who appear as slaves owned by Isabel Tellado and Juan Gonzalez de la Cruz in the 1826 “ relación de esclavos” de Moca. These slaves were married apparently in 1810 in Moca, and I presume Manuel adopted Tellado surname from lady owner Isabel. Have been unable to secure further info. Any advice appreciated. Thanks

Hi Miguel, thanks for writing. Manuel & Maria Andrea actually appear in Antonio Nieves Mendez’ Moca (2008) Tabla VIII. Esclavos y esclavistas de Moca entre 1810-1824 on page 362.

Juan González e Isabel Tellado were the enslavers of Manuel & Maria Andrea who had the following children: María Concepción, María Andrea.

The couple also held Pedro & Dorotea, parents of Manuel, and another woman, Lorenza. It’s possible there was some relationship among them.

Given the 1810-1824 dates, Manuel and Maria Andrea have had two daughters by this time, so at the very least, we can estimate that Maria Andrea was born between 1790-1796, between ages 14-20.

The marriage record is listed in Nieves Mendez also: 1810 Manuel y María Andrea de Juan González de la Cruz. So their first child, Maria Concepcion [Gonzalez de la Cruz] is born about 1810.

So that would make them Gonzalez rather than Tellado if they used the enslaver’s surname.

So far from what I am reviewing there are only a couple of Tellado families about 1800 in Moca, Valerio Tellado + Josefa Vazquez, who may also be the parents of Isabel; they may have lived in Barrio Plata or surrounding barrios.

Note that they are not listed in the 1826 Relation de esclavos in Table XIII. Can I ask how you worked back to them? They may be mentioned in any wills or bills of sale; a few were able to purchase their freedom. Ysabel could have inherited Manuel or the couple is actually separately owned by husband and wife– note there are no surnames here for Manuel and Maria Andrea, only first names. You need additional documents to show what happened to them, if they were able to gain freedom or are entered in a different parish; their enslavers could have moved to San Sebastian or another municipality. You may find them in census among the Municipal Document series on the ADNPR.net- and while the Cajas are not indexed, perhaps you can search them using AI.

At present, there’s a Concepcion Tellado of Bo. de la Torre, Lares in the 1870 cedulas in Caja 2 of the Registro de Esclavos series, with a daughter Dolores & she was buying her freedom for 300 escudos: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSK3-C3WY-C?cat=612874

Hope this helps,

Ellen

Thank you for your very informative response. I actually found Maria Andrea’s death certificate of 1889 ( who apparently lived until age 97) and she is listed as daughter of Dorotea ( natural de Africa) and her deceased spouse as Manuel Tellado. That is puzzling because if Manuel’s mother is also Dorotea that would make them siblings. They had a child around 1819 named Damian Tellado, which is where I descend from . Damian is my father’s great grandfather. Manuel and Maria Andrea show up as being married as slaves in 1810 in Moca and apparently had a daughter few years afterwards named Concepcion Tellado who might be the slave listed in 1870 , which was liberated by a slave-owner named Felipe Arana in Lares ( I also found the proclamation by the Spanish king congratulating slave holders who liberated their slaves ( 1872)

Hi again Miguel,

There’s an error in the death record for Andrea Perez’ death certificate– Damian did indeed go to report the death and was recorded as tio instead of hermano.As Damian couldn’t read or write at that point, he may not know what the document said.

I believe he may be the same person in the 1910 census- Ramon D. Tellado, N, 80 agricultor in Lares and he was able to purchase his land. See here: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYBD-5Y?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AVWKK-D89&action=view

Andrea Perez’s children with Manuel Tellado were Concepcion, Pablo, Francisco, Juan, Bonifacio, Damian, Socorro, Placida y Lorenzo– definitely look them all up for additional details- you can see Bonifacio listed among her children here. I added them to the tree on FamilySearch. Her death record says Manuel Tellado was born in Moca and that she is the daughter of Dorotea Perez natural de Africa. There are several different enslavers involved in the family, which moved away from Aguadilla/Moca to Lares after their freedom. Also the numbers for persons released by their enslavers is quite small in comparison to the thousands going through emancipation, and sometimes involved their own families.

There’s more to discover, however you’ll have to go through different kinds of documentation to see if you can locate something else– his land records, which means he probably had a will, so the notary documents and municipal documents may have more on them. I think they may have obtained their freedom before 1868-1870, otherwise they’d show up in the records under PR Slave Records on FS. Let me know how it goes, Best, Ellen