My career has differed materially from that of most women; and some things that I have done have shocked persons for whom I have every respect, however much my ideas of propriety may differ from theirs. Loreta Janeta Velazquez, (1876) The Woman in Battle.

On our recent Black ProGen episode on Civil War Pension files had me wondering about Caribbean ties to the Civil War. As I learned, there were some 3500 soldiers and officers in the Civil War who were Latino, 2500 of them served the Union, while 1000 served the Confederacy with the number rising to 10,000 by war’s end.

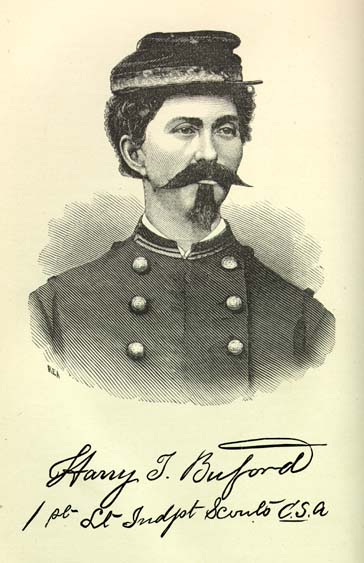

I came across a Puerto Rican born Union officer, and a Cuban born woman with a remarkable story… and a mustache and goatee.

My aim here is not to do a Civil War blow by blow of her military service, but to weigh in on genealogical details concerning her identity based on what I could find in various archival databases. I also want to express my thanks to Nicka Smith, Bernice Bennett, Shelley Murphy and Teresa Vega for discussions about the Civil War, pension files and the great city of New Orleans. This is excerpted from a longer work.

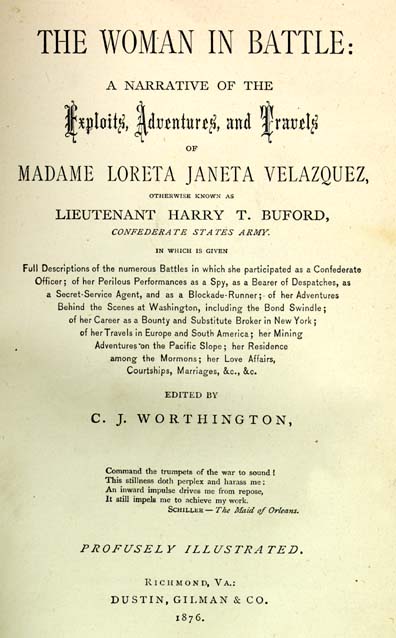

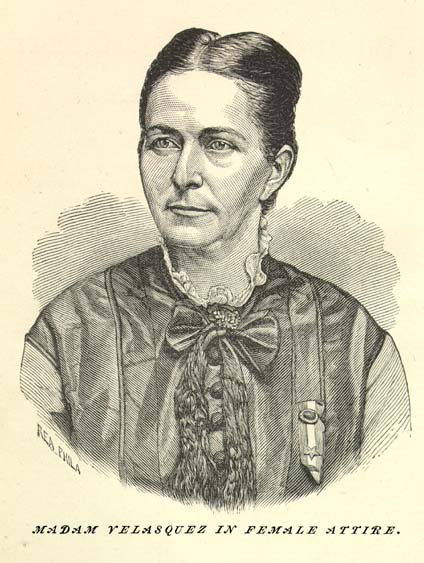

Loreta Janeta Velazquez published her exploits in her 1876 memoir, The Woman in Battle. She was known for crossing many lines, ultimately serving the Confederacy as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford. The book’s title page and frontispiece are designed to first assure the reader that the author is indeed a female, while luring the reader with the excitement and experiences reserved for white men across the country and two continents. There is innuendo, as suggested by where she lived and who she loved by the end of the 118 word title. It has everything packed into it for 1876- spying, violence, money, and sex.

The full title reads like a film summary:

THE WOMAN IN BATTLE: A NARRATIVE OF THE Exploits, Adventures, and Travels OF MADAME LORETA JANETA VELAZQUEZ, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS LIEUTENANT HARRY T. BUFORD, CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY. IN WHICH IS GIVEN Full Descriptions of the numerous Battles in which she participated as a Confederate Officer; of her Perilous Performances as a Spy, as a Bearer of Despatches, as a Secret-Service Agent, and as a Blockade-Runner; of her Adventures Behind the Scenes at Washington, including the Bond Swindle; of her Career as a Bounty and Substitute Broker in New York; of her Travels in Europe and South America; her Mining Adventures on the Pacific Slope; her Residence among the Mormons; her Love Affairs, Courtships, Marriages, &c., &c.

EDITED BY

C. J. WORTHINGTON,

The dedication lets you know right away what side she was rooting for:

TO MY

Comrades of the Confederate Armies,

WHO, ALTHOUGH THEY FOUGHT IN A LOSING CAUSE,

SUCCEEDED BY THEIR VALOR IN WINNING

THE ADMIRATION OF THE WORLD,

THIS NARRATIVE

OF MY ADVENTURES AS A SOLDIER, A SPY,

AND A SECRET-SERVICE AGENT,

Is Dedicated,

WITH ALL HONOR, RESPECT, AND GOOD WILL.

Velazquez is very much the rolling stone, moving from one location to another across the United States, Caribbean and Europe between the time she was born throughout her adulthood. I’m working on a longer version of this essay, and wanted to share some of the aspects of her story that go well beyond oral histories and memoir. What’s also fascinating is that she is a self made woman who basically studied men; whose genealogical presence failed to produce a tree with descendants, but instead gives us an opportunity to weigh what it means to tell and retell her story in different contexts.

Narrative, genealogy and hidden stories

Reading this text as a genealogist, there’s a big red flag at the outset of Velazquez’ memoirs— the loss of notes paired with a pressing need for income (emphasis added) for a book 376 pages long:

“… The loss of my notes has compelled me to rely entirely upon my memory; and memory is apt to be very treacherous, especially when, after a number of years, one endeavors to relate in their proper sequence a long series of complicated transactions. Besides, I have been compelled to write hurriedly, and in the intervals of pressing business, the necessities I have been under of earning my daily bread being such as could not be disregarded, even for the purpose of winning the laurels of authorship. To speak plainly, however, I care little for laurels of any kind just now, and am much more anxious for the money that I hope this book will bring in to me than I am for the praises of either critics or public. The money I want badly, while praise, although it will not be ungratifying, I am sufficiently philosophical to get along very comfortably without.” [WIB 6]

She worked with an editor, CJ Worthington,, a Naval veteran, who ‘although during the war was on the other side… has shown a remarkable skill in detecting and correcting errors into which I had inadvertently fallen.”

For Worthington, however, the importance of the book is not her gender crossing but spy craft:

In the opinion of the editor, however, the most important part of the book is that in which a revelation is made, now for the first time, of the exact manner in which the Confederate secret-service system at the North was managed. There is no feature of the civil war that more needs to have light thrown on it than this; and, as the story which the heroine of the adventures herein set down recites, is an exceedingly curious one, it is deserving of the special consideration of the public, both North and South.

The South was mistaken, but one couldn’t ‘doubt their sincerity or honesty of purpose.’ [10] He calls Velazquez ‘a typical Southern woman of the war period’. Oh, right.

Worthington says of the manuscript (emphasis added):

“The manuscript, when it was placed in his hands, was found to be very minute and particular in some places, and rather meagre in others, where particularity seemed desirable. Having undertaken to get this material into proper shape, correspondence was opened with Madame Velazquez, and a number of interviews with her were had. A general plan having been agreed upon, it was left entirely to the judgment of the editor what to omit or what to insert,–Madame Velazquez agreeing to supply such information as was needed to make the story complete, in a style suitable for publication. From her correspondence, and from notes of her conversations, a variety of very interesting details, not in the original manuscript, were obtained and incorporated in the narrative. The editor, also, in several places has corrected palpable errors of time and place, and has added a few facts not supplied by the author.” [11]

“Owing to the loss of her diary, Madame Velazquez was compelled to write her narrative entirely from memory, which will account for the errors to which allusion has been made. Indeed, considering the multiplicity of events, it is very remarkable that she has been able to relate her story with any degree of accuracy. It is possible that, despite the pains that have been taken to make the narrative exact in every particular with regard to its facts, a few errors may have been permitted to remain uncorrected. These errors, however, are not material, and do not in any way impair the interest of the story.” [12]

Velazquez herself admits to generating ‘alternative facts’ as needed, which was frequent while she served as a spy or officer in drag and for excuses to the young ladies who find themselves drawn to the ambiguously gendered officer: [111] “… I made up a story that I thought was suited to the occasion and the auditor; and, among other things, told her that I was the son of a millionnaire, that I had joined the army for the fun of the thing, and that I was paying my own expenses.”

Later in the book she takes on blockade running, purchasing supplies, donating money and scamming funds for the Confederate cause during and after the Civil War. Still, her argument for the national fight is the win, not the economic structure that locked so many in, and built the structure of inequality based on race. One could argue that she is an example of working with family histories that present a particular point of view that can bring into question ideas of self fashioning with a basis in forms of systemic inequality. It is the polar opposite of Abolitionist writings.

Velazquez’ family

Velazquez’ book begins with two genealogies— one of women in war that culminates in her being the ideological heir of Joan of Arc, the other, is of a nobility clawed out of the Caribbean, belied by newspaper articles of mid-1863 that spoke of her exploits in the service.

According to her, she was born on 26th of June, 1842, the last of six children on Calle Vellagas, just outside the walls of Havana, Cuba, Loreta Janeta Velazquez states that her father was a Spanish Ambassador born in Cartagena, (implied) Spain, of noble descent. Her mother was from France, daughter of a French naval officer and an American heiress. Her mother’s only brother resided on St. Lucia, but this is not explained in more detail until much later in the book.

Her parents had three sons and two daughters born in Madrid before her birth in Cuba, but in between the time of his appointment to the time of her birth in 1842, the family moved across continents and oceans. Her father is an aristocrat, a learned ambassador who spoke at least three languages, and ultimately supported the Southern cause. The weight of his experience and wealth serve to anchor any charge regarding class in terms of Loreta’s social standing and wobbly gender identification in her memoir. She mentions her brother Josea and a family reunion in St Louis, but is careful not to name her parents in any detail beyond that of moral standing until 1891, when a New York newspaper article quotes her saying that father’s name is Joaquin Velazquez.

For her ancestral lineage, she invokes a conquistador of the New World, Diego Velazquez de Cuellar, (1465-d. 1524, Santiago de Cuba), an interesting choice: Velazquez led the conquest of Cuba with 300 men in 1511, noted for being a particularly brutal episode. Just as with Columbus, those Indigenous people that resisted, if not killed or maimed, were sold into slavery across the Atlantic and to Mexico, Central and South America to work the mines. It did not go as planned, so he authorized the importation of enslaved Africans in 1513, and an expedition to the Yucatan. He lost his governorship in 1521 for the misuse of indigenous labor, facts that never ruffle the lineage.

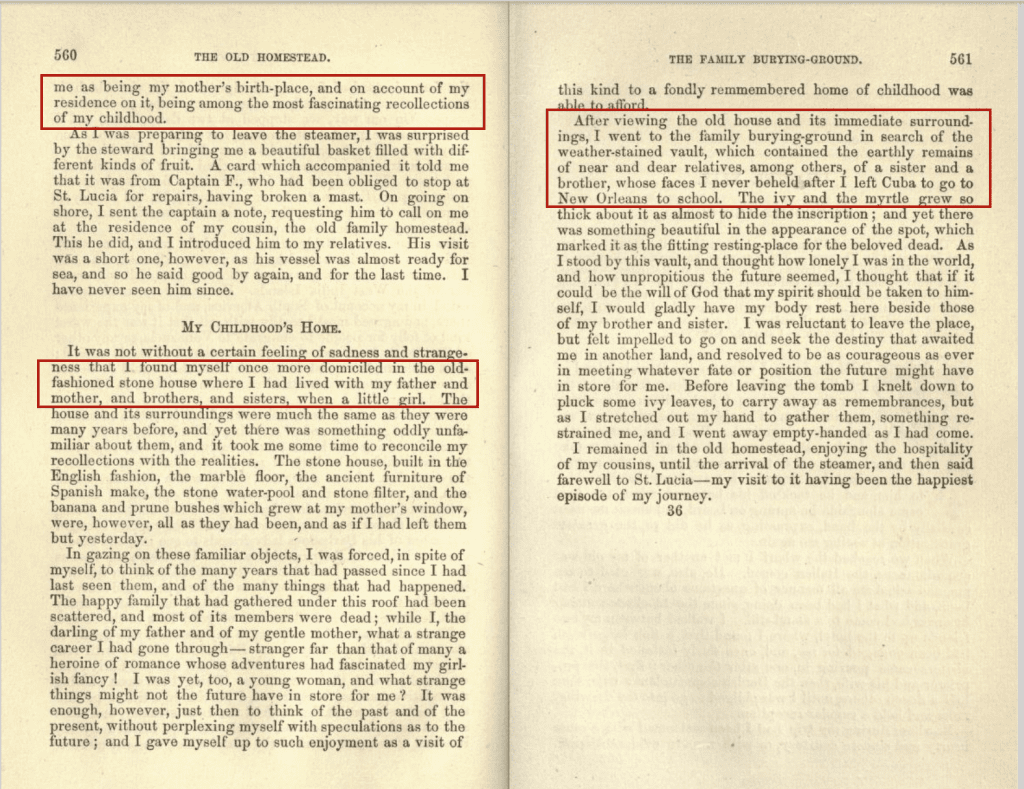

As mentioned, she describes visiting various Caribbean islands, and at Saint Lucia, states that this is where her mother was born:

The connection to Saint Lucia, with its family cemetery and vault, a stone cottage that she describes, now owned by her cousin. The house itself, like the family, is a hybrid site, ‘a stone house built in the English fashion’ with ‘ancient furniture of Spanish make.’ Both her unseen sister and brother are entombed in the family burying-ground, together with other relatives in St. Lucia. No further details regarding which port she entered, what parish the family once lived in, is given for locations she mentions before 1868. [WIB 566]

The Many Names of Lorena Janeta Velazquez

Another flag in the text and in newspaper accounts are the various aliases she used over four decades (if not longer). It’s an unusually long and overlapping set of identifiers:

Loreta Janeta Velazquez

Mrs. Alice Williams

Mrs. Alice Tennent

Mrs. ST Williams

Mrs Major De Caulp

Mrs Loretta De Caulp

Mrs DeCaulp Buford

Mrs Loretta J. Beard

Mrs Sue Battle

Lieutenant Roach

Lieutenant Bensford

Lieutenant HT Buford

She was married to:

ST Williams, army officer,

Major Jeruth DeCaulp

Major Wasson, confederate officer, married in New Orleans

‘Col.’ W Beard

Perhaps the person that can be confirmed in her account is DeCaulp. ‘Major’ Jeruth DeCaulp was born in Edinborough, arrived in 1857 with his brother, and they traveled the US until 1859, and signed up for the confederacy when the war broke out. “His father was of French descent, and his mother was a Derbyshirewoman. “He was very highly educated, having studied in England and France with the intention of becoming a physician. His fondness for roaming, however, induced him to abandon this design.. He was tall in stature, with a very imposing presence. His hair was auburn, and he had a large, full, dark, hazel eye.” It is unclear whether that referred to a pair, or the result of wartime injury.

His brother held the rank of Captain and died in Nashville at the close of the war; his wife died in New York. Despite the call to his standing, DeCaulp’s extant letters are full of spelling errors such as ‘cince’ for since, details that cast doubt on his education. Velazquez has elaborate backgrounds for her husbands and her parents, and if its too good to be true, it probably is.

Reviving Loreta Velazquez

Running into a historical figure like Velazquez is both exhilarating and troubling. There’s the fact of her intense, incredulous story that she tells and then there’s the reality of locating information. At first, I came across the image of the goateed Velazquez, and a broader history of the involvement of women in the military. Next, there is the documentary, Maria Angui Carter’s Rebel (2013) which establishes Velazquez’ existence, but does not really suss all the details regarding her ancestry. Instead, it’s presented as fact, because it was published, which has a circular, closed kind of reasoning. There’s no argument that Velazquez worked to further the aims of the Lost Cause. Then there is historian William C Davis’s book, Inventing Loreta Velasquez: Confederate Soldier impersonator, Media Celebrity and Con Artist. (SIU: 2016). Davis strains through newspaper accounts and establishes that it is likely you couldn’t trust what Velazquez has to say about family, lineage or history.

Whose side are you on?

One of the things I found disturbing was no real engagement with what it meant to identify with a supposedly light skinned Latina who fought for the Confederacy, without really unpacking the weight of that affiliation. What Loreta discovered was that her ‘possessive investment in whiteness’ had a pay off. People could deal with a Cuban better than say, a mixed race child from New Orleans or Mississippi, instead a Cuban with alleged ties to minor nobility and foreign governments was much more appealing. Ultimately, nostalgia is what Velazquez supplies, full of the dream of the South’s ‘hotel civilization’, where dirt, mess and disorder were disavowed and left for the enslaved help to deal with. What of 18 year old Bob, the young man she bought and enslaved to serve her in the field, who ultimately ran off to the North to claim his freedom? Why the silence on the enslaved help who would have served her family?

A reference

In case you’re wondering about ‘hotel civilization’: It’s a great term that Cornell West coined in the 1990s. “We live in a hotel civilization,” said West. “A hotel civilization is a civilization in which people are obsessed with comfort, contentment, and convenience, where the lights are always on. [We] don’t have time for questions. We don’t have time for such interrogations.”

Frankly, America always has been a hotel civilization. This is no joke. West continues: “To escape the pull of the American culture of denial, West urged individuals to examine and question America’s “night-side” – the dark under-belly of society. He added that part of this process of enlightenment is acknowledging real death and violence and also experiencing metaphorical death.

“We must come to terms with the forms of death in the midst of the American past and present. Education itself is a learning how to die. Every time you give up an assumption. it’s a form of death so you can mature,” said West.