Mary Turner’s life ended 19 May 1918 in Lowndes County, Georgia at the hands of a lynch mob, as a result of vowing to hold those responsible for killing her husband, Hazel Turner. She was arrested once she spoke for justice, and the town leaders retaliated. Mary Turner declared that Hazel Turner’s killing “..was unjust and if she knew the names of the persons who were in the mob who lynched her husband, she would have warrants sworn out against them and have them punished in the courts. This news determined the mob to “teach her a lesson”…” [Walter F White,“The Work of a Mob.” The Crisis, NAACP, Sept 1918, 221-223’]

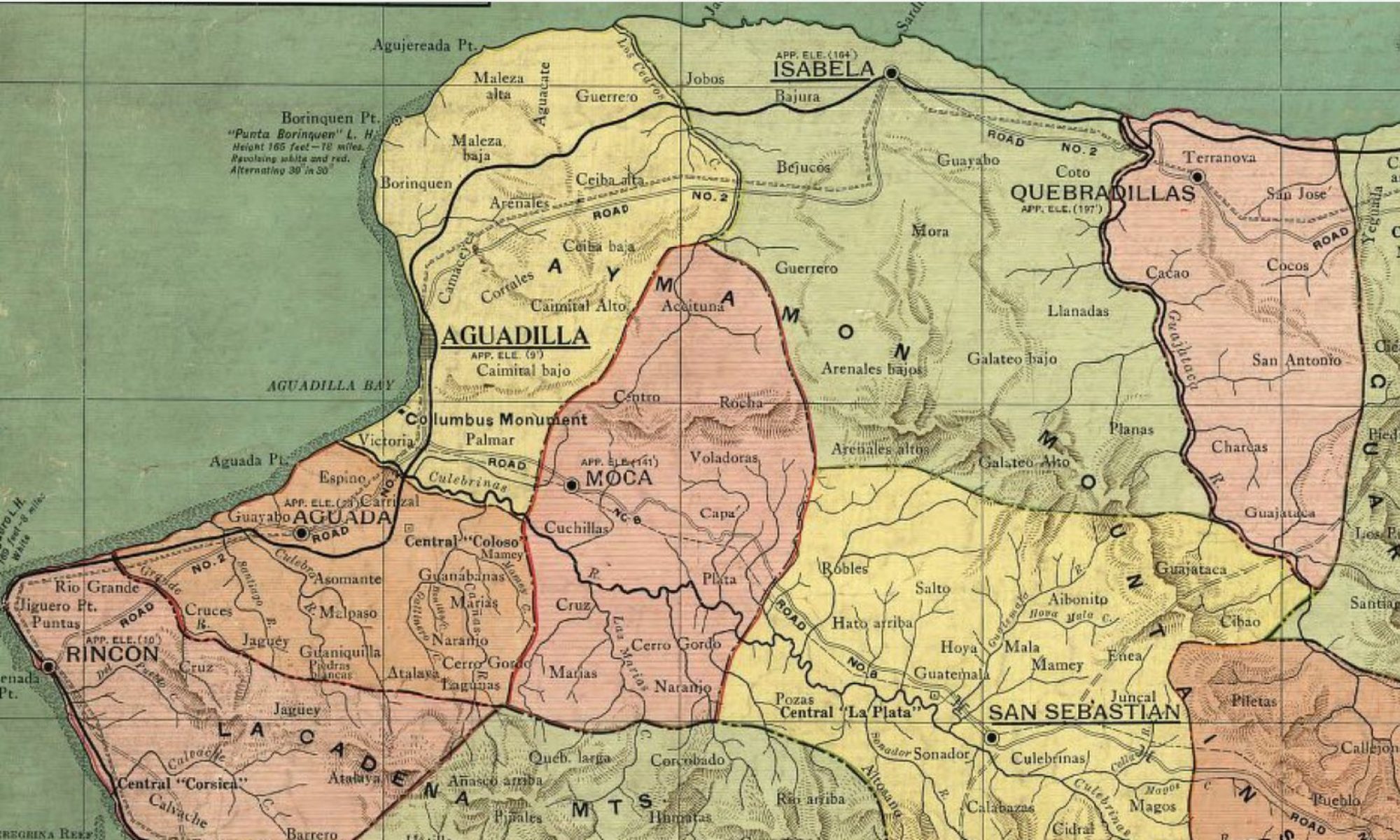

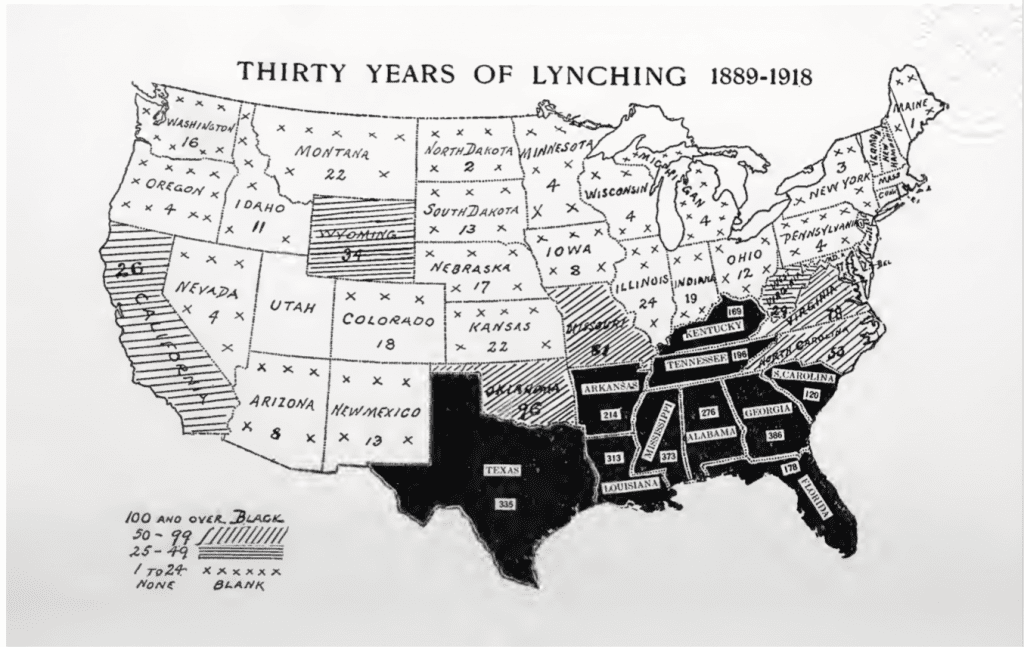

What followed was her lynching and that of her unborn child on the Folsom Bridge that connects Brooks and Lowndes Counties. Its important to know that the area wasn’t immune from violence. Some twenty-four years earlier, in Christmas 1894, five African American men were lynched by local whites in what was called the ‘Brooks County Race War’.

Also lost in May 1918 were the lives of 16 other persons, including her husband, Hayes Turner, who died the day before. That she and her unborn child were executed was held up as some kind of boundary violation, obscures the fact that three times the number of enslaved Black women were executed in antebellum slavery as in colonial slavery. While far fewer women were executed during Reconstruction, mostly in the South, terrorizing communities was a means of control used in many locations across the US after the Civil War. [ Meyers 2006, p5] Ten women were lynched in Georgia between 1880-1930 [Meyers 2006 224]

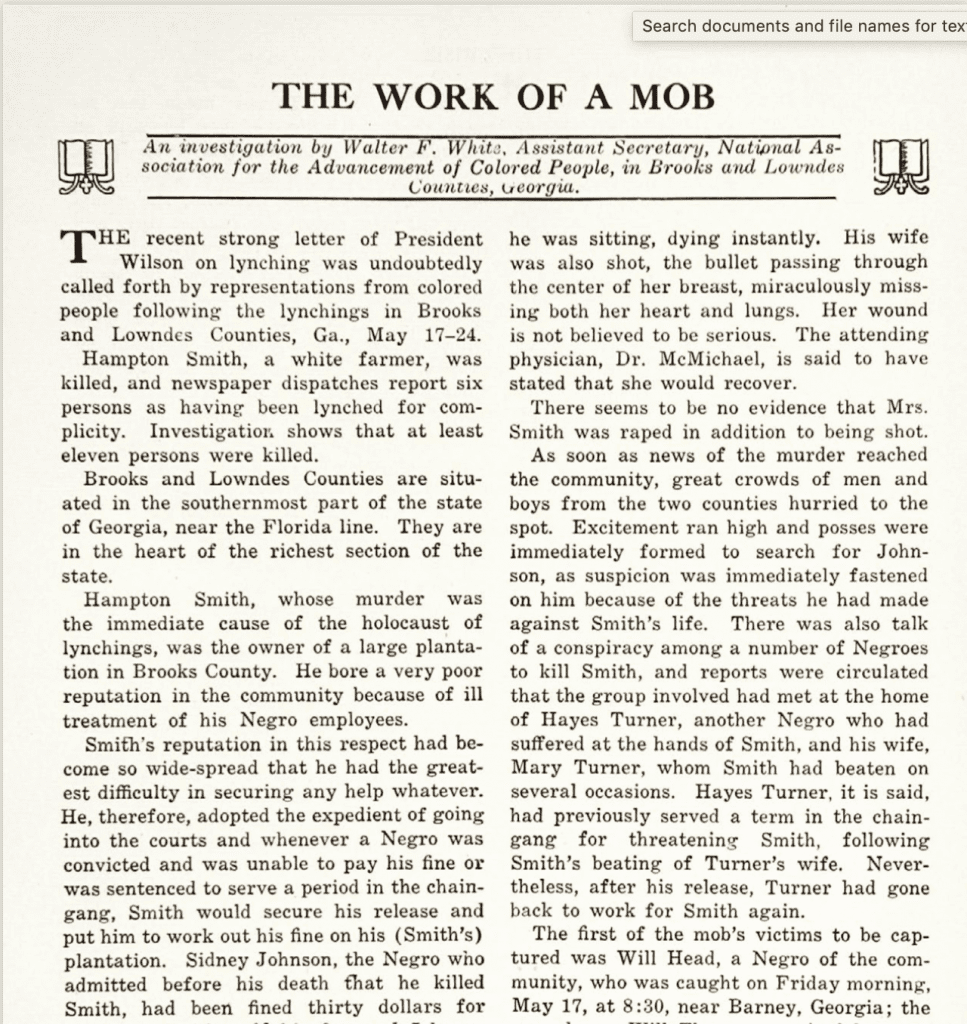

What is notable is the participation of the white business community and law enforcement in these series of murders. According to a witness, those who participated in the mob were led by Samuel E McGowan, an undertaker and William Whipple, a cotton broker and merchandise dealer, both of Quitman. Ordley Yates, post office clerk, Frank Purvis, employee of Griffin Furniture Company, Fulton DeVane, agent for Standard Oil Company, Brown Sherill, worked for Whipple, George B Vann, barber from Quitman, the farmers Chalmers, Lee Sherrill, Richard DeVane, Ross DeVane, Jim Dickson, Dixon Smith (father of Hampton Smith) Will Smith (brother of Hampton Smith) and two other brothers of the victims all participated. [Meyers 2006 221; Walter F White, 1918]

Their names are known because of the investigation undertaken by Walter F White, on behalf of the NAACP, and the testimony of George U. Spratling, an African American man who was an assistant to the undertaker McGowan. Spratling was forced by McGowan to go to the lynching, where none wore masks to evade identification.

Eighteen people total died between that Friday and Saturday. Hayes Turner was caught on Saturday, captured and taken to the Brooks County Jail in Quitman, then transported to Moultrie, where Sheriff Wade and Roland Knight, clerk of the county court were waylaid. Turner was taken by the mob and murdered.

NAACP: Intervention, Investigation & Recommendations

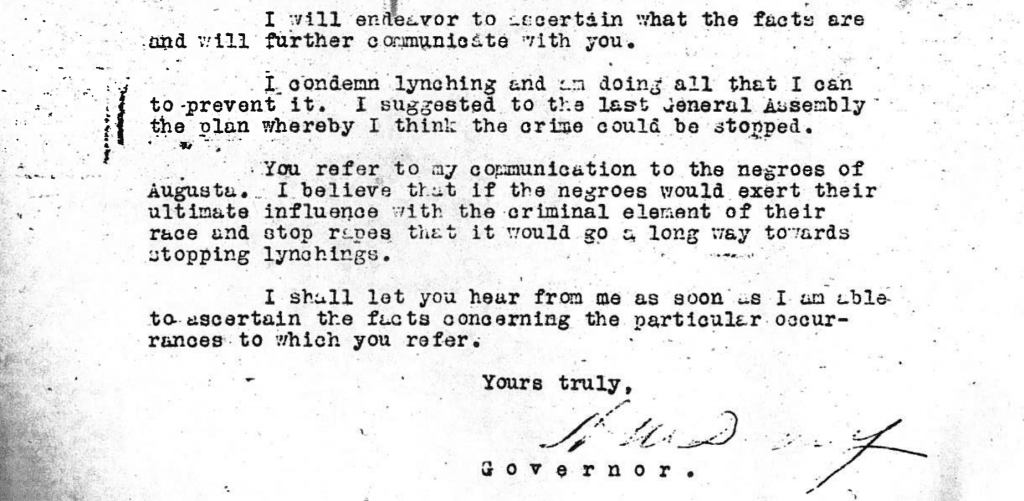

Governor Dorsey ordered militia troops to the area, but it was too little, too late. He questioned his authority to arrest those involved. However, aware that the African American migration out of the state had begun with some 500 people departing Lowndes County shortly after the mass lynching occurred, the state was set to lose workers as the Great Migration intensified. Among those able to leave the state were members of the Turner family.

Dorsey’s reply to the NAACP letter notifying him of the events in Lowdnes is reprehensible. He basically blames Black people for the lynching rampage: “I believe that if the negroes would assert their ultimate influence with the original element of their race and stop rapes that it would go a long way towards stopping lynchings.”

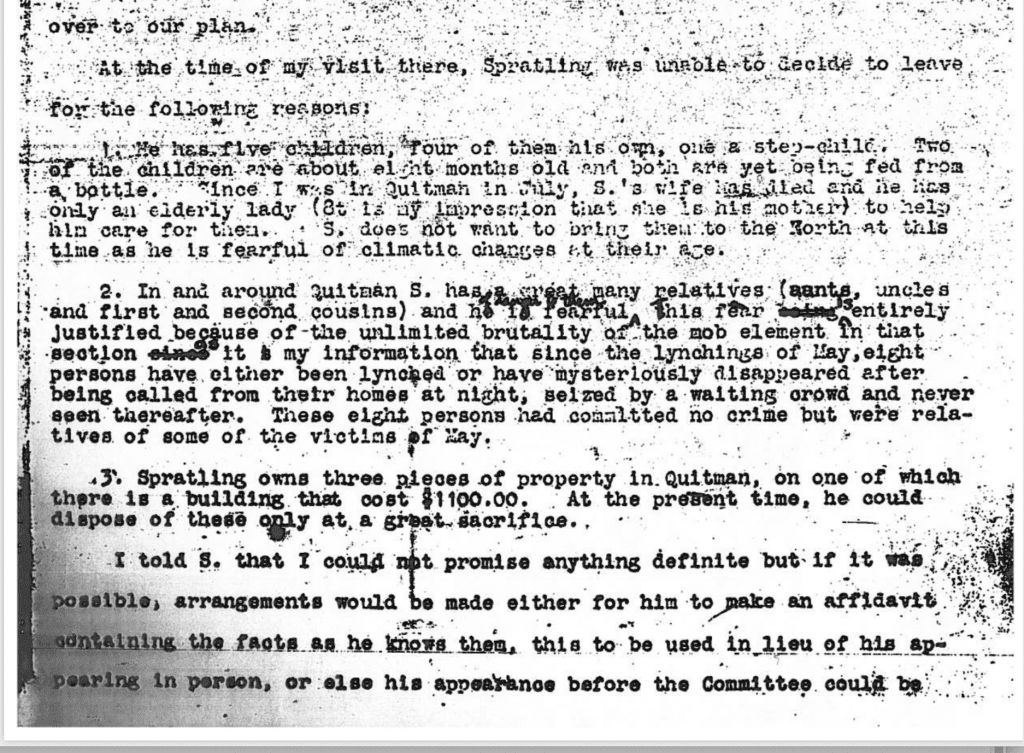

The NAACP made the Turner case a central concern and pursued investigating the event soon after. They made an offer to assist George Spratling with relocating to the North, help with gaining employment there and support him until the hearing was completed and he was able to go to work. But he couldn’t just leave- he had 5 young children to care for along with a wife and an elderly lady, and ‘a great many relatives (aunts uncles and first and second cousins)’ in and around Quitman. [Letter from Walter White to NAACP Secretary concerning lynching witness George Spratling, November 12, 1918 (from NAACP Papers Collection)

White notes that “since May eight people were either lynched or went missing; they committed no crime but were relatives of some of the victims of May.” Clearly, racial terrorism was a tool that the NAACP focused on dismantling or at the least, ameliorating its spread by revealing its inner workings and demystifying the feeble excuses offered by local and federal government to a broader public through its publications and newspaper articles.

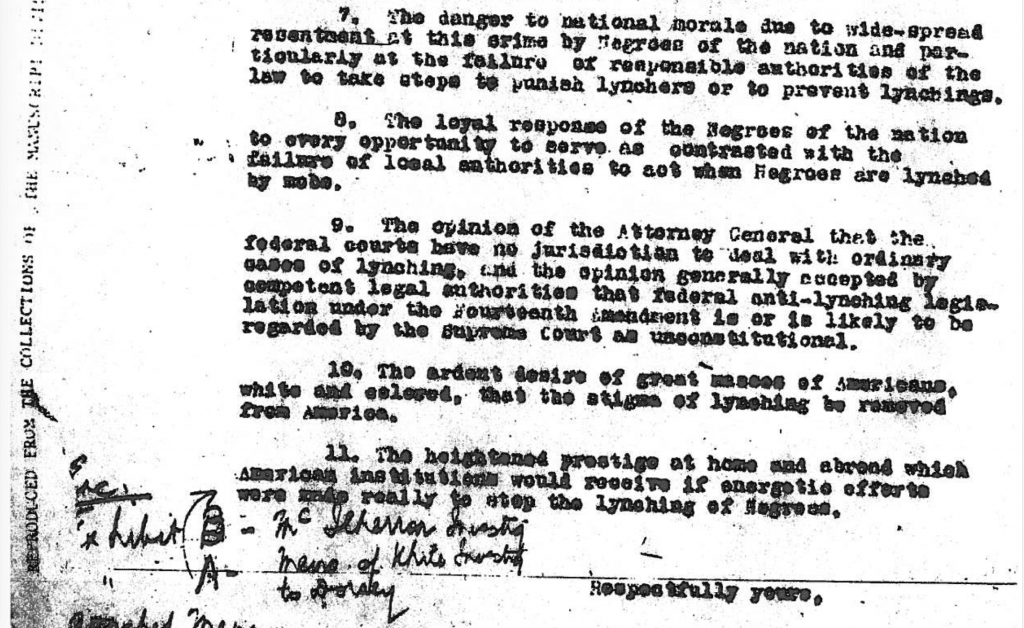

The organization wrote to President Woodrow Wilson to urge him to act and spelled out why this should be a concern:

“8. The loyal response of the Negroes of the nation to every opportunity to serve as contrasted with the failure of local authorities to act when Negroes are lynched by mob.

9. The opinion of the Attorney General that the federal courts have no jurisdiction to deal with ordinary cases of lynching, and he opinion generally accepted by competent legal authorities that federal anti-lynching legislation under the Fourteenth Amendment is or is likely to be regarded by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional.

10. The ardent desire of great masses of Americans white and colored, that the stigma of lynching be removed from America.

11. The heightened prestige at home and abroad which American institutions would receive if energetic efforts were made really to stop the lynching of Negroes. “

What is interesting is the insistence that this event and other incidents of terrorism is not America- ‘this is not who we are’. Essentiality it is a failure to live up to the expectations by citizens and the world, right after participating in the first World War.

White sent the investigation on to President Wilson, who basically did nothing to stop the perpetrators.

After the lynching of Claude Neal in Florida in 1934 [Ep. 83], the NAACP circulated the story of Mary Turner, complete with an illustration of the lynching, in the NY Amsterdam News and Philadelphia Inquirer.

Economics, Kin, Networks

The Turners labored incessantly and suffered beatings as part of being in a debt peonage system. Hampton Smith (whose death marked the start of what was called a ‘holocaust of lynchings), was the owner of the large plantation in Brooks County that they and others worked on, had a terrible reputation for violence and terrorizing his workers. As a result, he had difficulty securing workers, and went to the courts and whenever a Black man “was convicted and unable to pay his fine or was sentenced to serve a period on the chain gang, Smith would secure his release” and put them to work on his plantation, until the amount in question was paid off. [White, “The Work of a Mob.,” 1918, 1] Apparently workers never made enough to satisfy the debt and according to accounts suffered beatings at his hands, and one young man resisted and decided to kill him.

The issue of debt peonage was never addressed, and was a huge problem across sites in Georgia, Florida and Alabama.

The disruptive effects of this mass lynching impacted the future of the families. If they could, they moved to other counties or across the state line to start over.

Aside from this, each family had female headed households that helped their children survive the transition from enslavement to emancipation. By design, there were insufficient resources to keep people laboring rather than able to pursue their own path, and sadly, some family members were unable to escape the trap of debt peonage and the prison convict system.

Mary Turner- Mary Hattie Graham (1884-1918)

Mary Turner’s full maiden name was Mary Hattie Graham, daughter of Perry W. Graham and Betty Johnson (1872).

Her story inspired artist Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller to create Mary Turner: A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence. This is an early anti-lynching memorial, which also incorporates genteel standards of womanhood of the time. Still, this is a figure beset by trouble, her face almost hidden and body that tries to keep to itself. Hands appear on the lower third, with a face sunk into the crowd, which suggests more horror as one spends time with the work.

Mary Hattie Graham was born in Quitman, Brooks County in Dec 1884 to Perry Graham and Betty Johnson Graham. Her father’s mother was born in Virginia, according to the 1910 census. By that time Perry Graham and Betty Johnson Graham were married for 29 years; they married in Lowndes County on 18 Nov 1880.

By 1910, her brother, Perry J Graham had set up his own household alongside their parents in Briggs, Brooks County, GA. With Dora Stoker, he had 16 children. By 1930, both generations lived together in Briggs. As their family was large, mobility was limited, and the next generation would migrate out of the state. I haven’t yet found them in the 1920 census, which may mean they avoided the enumerator or changed names to stay safe.

By 1940 at least one son of Perry and Dora, Melvin J Briggs b. 1908 had moved to Miami, Dade County, Florida from Valdosta after 1935. He worked as a bell hop in a hotel, rooming with a group of people who also came from Georgia. While he may not have traveled north, he was part of a larger migration out of state by African Americans who sought self determination.

Betsey or Betty Johnson

Turner’s mother, Betsey or Betty Johnson b. 18 first appears in the 1880 census, in the home of her mother, Phoebe Briggs, b. 1848. At that time Ms. Johnson is working as a servant, and has a daughter, Viola Washington. She is 21, older than listed in later census, born about 1859. If the dates are correct, Phoebe had her very young- she is 31 while her daughter is 21. The household comprises three generations.

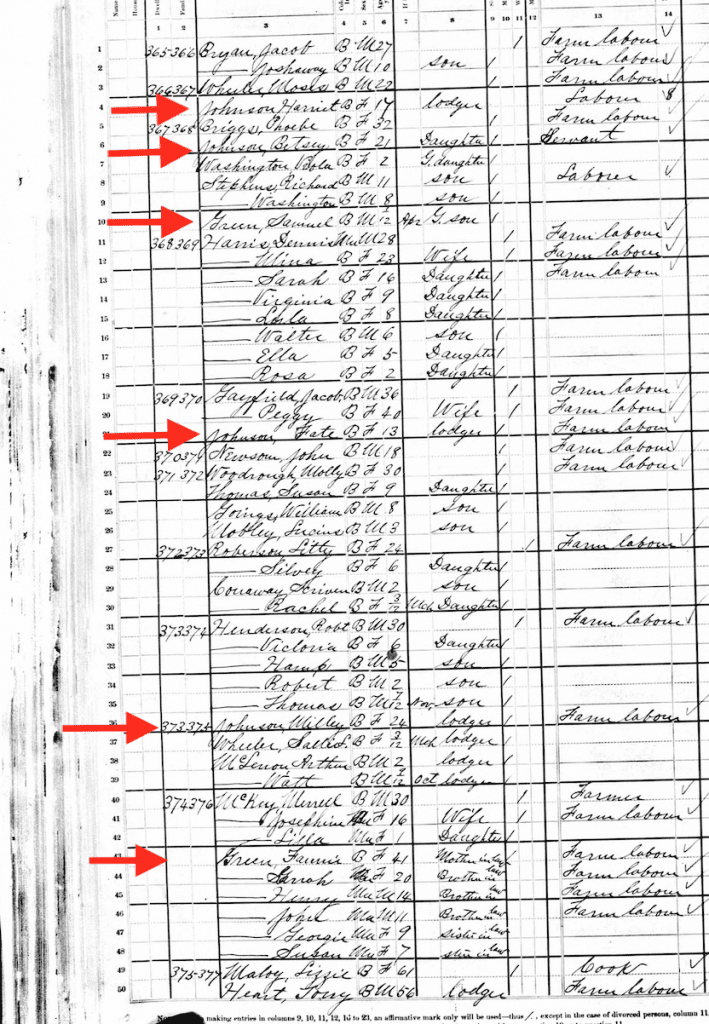

In 1880 Phoebe Briggs works as a farm laborer, and one of her young sons, Richard Stephens works as a laborer at 11 years of age; there is no occupation listed for his brother Washington Stephens age 8. Different states are listed for their fathers, which raises questions about the difficulties of Briggs’ situation with her partners post-Reconstruction 1869-1872 in the Valdosta district of Lowndes, Georgia. Also in the household is her 2 year old granddaughter from Betsey, Viola Washington and her grandson, Samuel Green, just a month old.

What is important to note, are the other Johnson females who live in adjacent homes— Harriet age 17 [Line 4] a lodger in the next house to Phoebe Briggs, and two doors down, Fate Johnson 13 [Line 21], lodger. There’s a Millie Johnson 24 [Line 36], and a Fannie Green 41, b.VA [Line 43], Mother in law to the McKays (in fact much of her family is lodging in the home of her daughter Josephine’s husband). It seems reasonable that the month old son may be tied to this family. They work as farm laborers, and some are close enough in age to be Betsey Johnson’s sisters, if not kin. This raises a few questions as to their relationship to Phoebe Briggs and her daughter, Betsey Johnson, and whether they are kin or blood relatives from the same community in this area of Valdosta. Just a few months later, in November 1880, Betsey Johnson married Perry Graham.

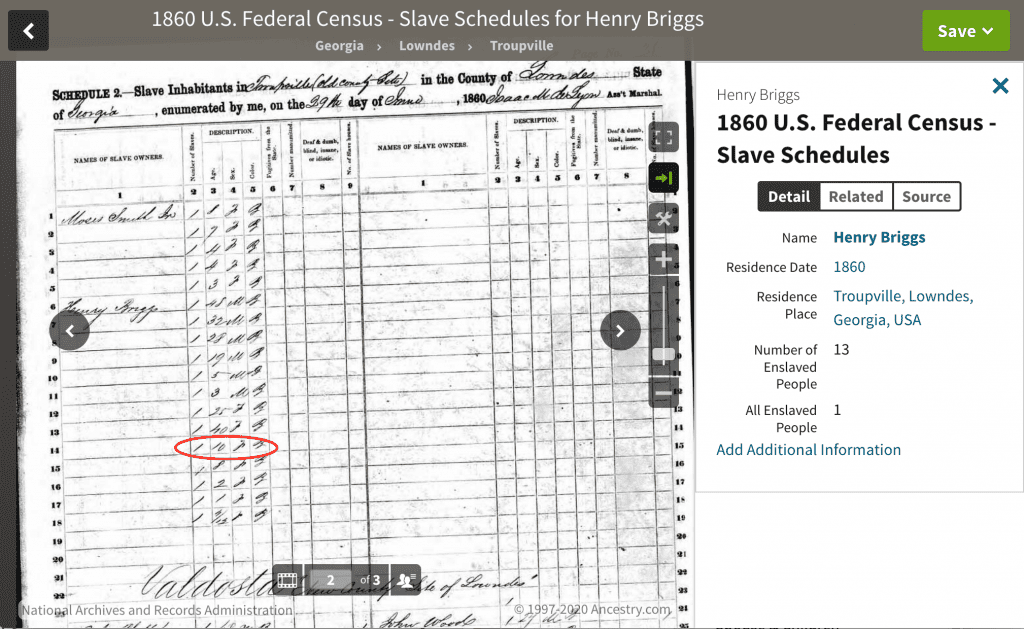

I was unable to locate Phoebe Briggs in the 1870 census. However, the 1860 Federal Population Census and Slave Schedule for Lowndes, GA- right at the start of Valdosta, shows a Henry Briggs with 13 enslaved people, including a 10 year old female, who could potentially be Phoebe Briggs.

The location of his plantation was at the end of Troupville, and Valdosta is the next town that starts just a few lines down. Additional probate and insurance documents can help identify the people he held in bondage, and confirm whether this number, is indeed Phoebe Briggs.

A page on the early history of Troupville also reveals a history of a settlement that begins with bloodshed as the new arrivals sought to displace the Creeks from their territory. Native peoples had lived in the region for 11,000 years, and during the early 1800s, many were farmers, and among the ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ depended on enslaved labor before displacement in a series of Indian wars that culminated in the Trail of Tears. A Dr. Henry Briggs was among the early settlers of the town, which benefited from its location on the border with Florida. This was historically part of a Native American trade network that extended north to present day Savannah. Settler colonialism is an important part of the larger context of this history.

Conclusion

It’s over a century since the deaths of Mary Turner, her husband Hazel Turner and 16 others. Extrajudicial murders continue with 20,000 dying at the hands of the police in the last two decades. The EJI notes that the dehumanizing myth of racial bias needs to be confronted, and reveals it as part of a continuum: “This belief in racial hierarchy survived slavery’s abolition, fueled racial terror lynchings, demanded legally codified segregation, and spawned our mass incarceration crisis.” https://eji.org/racial-justice/ This is incredibly toxic stuff.

Lynching shaped the geographic, political, social, and economic conditions that African Americans experience today. Critically, racial terror lynching reinforced the belief that Black people are inherently guilty and dangerous. That belief underlies the racial inequality in our criminal justice system today. Mass incarceration, racially biased capital punishment, excessive and disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were shaped by the terror era.

What stood out most was the continued disruption of lives because of racist terror, and the way the system worked to extract as much value from these people without acknowledging their humanity and a right to access justice, fairness and the ability to live without attack. They were forced to repeatedly start over, and their survival is a testimony to their resilience. To get beyond the narratives of their deaths to their family histories isn’t easy.

Since the 2000s, there has been a sustained effort by the community to shed light on these events, to come to a reckoning so that this terrorism can end. The Mary Turner Project succeeded in placing a historic marker that names the victims, maintains a website that continues to pull together newspaper articles past and present that documents a long process of healing.

Restoring the visibility of these families helps in understanding the dynamics that sought to constrain the lives of millions, all hidden beneath a thin veneer of American exceptionalism.

Update: 11 September 2020. The Mary Turner Project had to remove the historical marker because of the damage it sustained from being repeatedly shot to the point the metal was stressed so much it cracked. Regardless of this vandalism, that still doesn’t change the need to remember this event as part of our national history.

Read more:

https://www.wtoc.com/2020/10/11/mary-turner-lynching-marker-removed-after-recent-vandalism/

I want to express deep gratitude for The Mary Turner Project’s efforts on keeping this history current, providing resources on events and for their work on racial justice and healing on both a local and national level. And thanks to Nicka Smith for the opportunity to participate in Ep 121 of History Unscripted: Profiles in Racial Justice, Part 1.

References

The Mary Turner Project, http://www.maryturner.org/mtp.htm

The Mary Turner Project, Documents http://www.maryturner.org/documents.htm

Kerry Seagrave, Lynchings of Women in the US: the Recorded Cases 1851-1946. McFarland & Co, 2010.

Walter F. White, “The Work of a Mob.” The Crisis, NAACP. 221-223

Christopher C Meyer, ”Killing Them by the Wholesale”: A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 90:2 (Summer 2006) 214-235.

Letter to President Woodrow Wilson, July 25, 1918. NAACP http://www.maryturner.org/images/WhiteHouseLetter.pdf

“Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller”, Wikipedia. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Meta_Vaux_Warrick_Fuller

NAACP, “History of Lynchings.” https://www.naacp.org/history-of-lynchings/

EJI, Racial Justice. https://eji.org/racial-justice/