Come with me as I go through various documents in search of information on ancestors of Mr. Orlando Williams– his paternal Great-Great Grandparents. Several details led to new information and complications while looking for ancestral paths across several states: South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia and Florida.

I began this part of my search for more information on Anderson Williams with the 1880 census. Williams was born about 1830 in South Carolina; however his wife, Nellie (Nelly) Jones Williams was in the household for a Caleb Williams, a white farmer with several workers housed at his home. Nellie Williams worked as a domestic servant in the household, just doors away from the home of her husband, Anderson Williams, who worked as a servant for Herbert Lee, his wife and sister in law Clorsey Williams, a black family.

Just a decade earlier in 1870, they lived in the same household with their recently born daughter, Henrietta Williams. By 1880, Henrietta is not at home, and whether she was still alive, living with kin or succumbed to childhood illness is unknown at present. The earliest records for him so far are the 1866 Colored Census, his 1867 voting record and the couple’s 1869 marriage record, both for Marengo County, Alabama.

Caleb Williams (b.1850): Who dat?

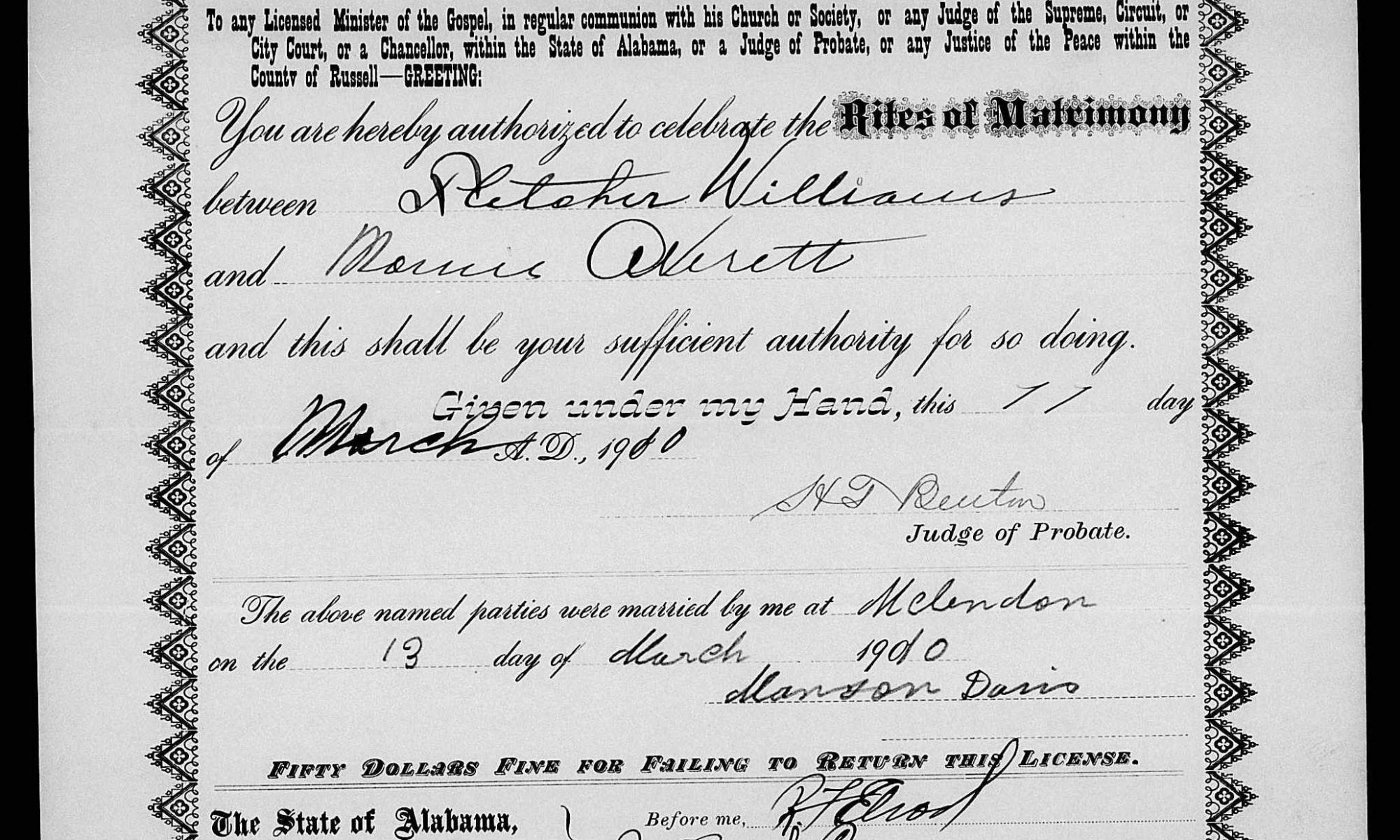

To find more on Caleb Williams I searched trees on ancestry.com and learned he was the son of Ashley and Elizabeth Williams; Ashley Williams was a planter born in Darlington, South Carolina. In the hopes of finding more about Anderson and Nellie Williams before 1866- when the first independent documentation of their lives as free people began, searching this family line made sense.

What one notes is the rapidity with which most of the information on the slave owner’s tree could be put together, unlike the families I’m researching. Instead, Anderson & Nelly William’s kin and community may be embedded in legal documents such as wills, inventories and writs of partition, and perhaps, newspaper advertisements, or other extant documents in courthouses or special collections.

There is no one path or one collection of documents that will answer all the questions, even the most basic. This is a process of constant cross referencing, and of developing a system to handle the archival items, be able to reference those resources. A spreadsheet becomes a key organizational tool, (especially if you use it).

Since this Caleb was too young to run his own farm in 1865, I began looking for his father’s estate papers in the Call County Courthouse in Marengo County, Alabama- these records were microfilmed on FamilySearch.org. I went through them, looking for Ashley Williams’ probate papers and inventories, however, these documents were elusive.

There were lots of delays in the process because of the Civil War- Ashley Williams served in the Confederacy and died in 1865. Whether he took one of the enslaved men as a servant in the field is unknown at this time. His wife, Elizabeth Davis Williams continued to shepherd the probate through the courts for years after the war, but the inventories that would list the people he enslaved seemed elusive with each postponement of the case .

At last, in Volume K, I found this entry dated 7 Nov 1867: on p 701, it reads: “This day RH Clarke Admin. filed inventory ordered same be reconsidered same be recorded” … But… the additional paperwork for this wasn’t present, and Emancipation was a couple of years earlier. Now what?

Strategies to go back to a different place & time

My next tactic, if those prior papers were no longer extant, was to go back a generation. Basically, find who Ashley Williams’ parents were, and then look for any probate papers for them. One possibility was that Anderson and Nellie may have been part of an estate subdivision by an inheritance from his father. Maybe they’d be mentioned somewhere in them.

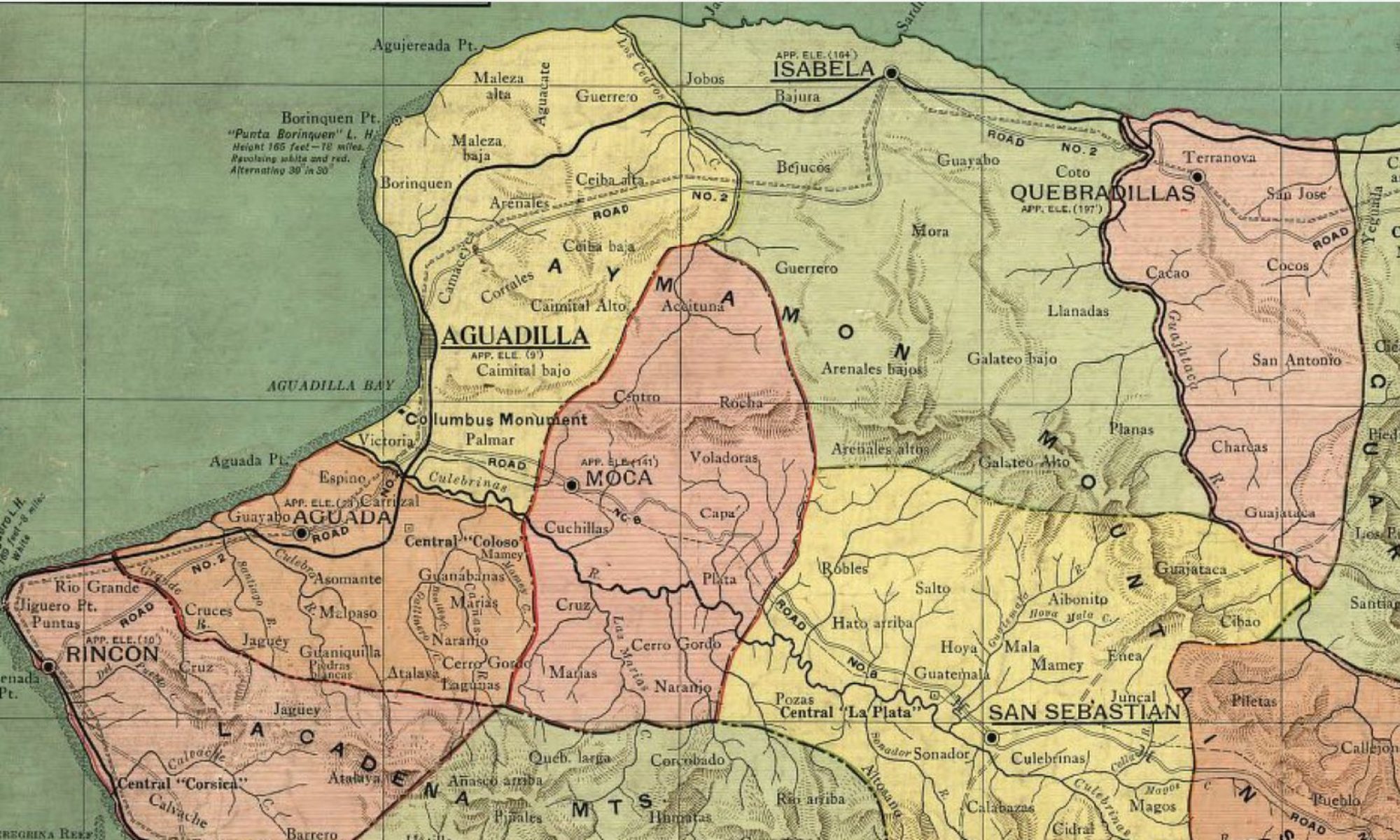

This meant the search moved north from Demopolis, Jefferson, Marengo County, Alabama to the place where Ashley Williams was born, Darlington South Carolina. Both Anderson and Nellie Williams’s census records record SC (and later, incorrectly as NC) as their original place of birth, so fingers crossed.

So, I began to search for previous inventories and appraisals for enslaved people held by William Williams (1754 – 22 Mar 1829) & Selah Fort (b. 1761) of Darlington South Carolina in anticipation that some subdivision of his estate occurred after his death and that those documents are extant. This may help solve the origin of relatives who are descendants of the enslaved that were forcibly marched or transported from South Carolina to Alabama in the early nineteenth century. As the family lines for the descendants of the enslaved also extend to Jackson County, Florida, the hope is that more clusters of relatives can be connected.

Subdividing the Estate, Subdividing Families & Kin

Among the beneficiaries of the Williams estate would be his wife and children. William Williams & Selah Fort’s son Ashley C Williams (1816-1865) was their third and last child born in Darlington, SC. After 1848, Ashley Williams moved south to Marengo County, AL after the birth of his first child, Amanda Jane. In 1853 he was named Justice of the Peace for Marengo County, Alabama. He died in 1865 while serving in the Confederate troops, leaving his wife Elizabeth and 6 young children.

Another of William & Selah’s children, Catherine Harriett Williams (1787-1821) died in Montgomery AL on 21 July 1821. Their son, David Williams (1784-1850) died in Darlington on 30 Oct 1850.

By building out a basic tree for the enslavers, I could then follow the marriages to see how enslaved families were subdivided, and follow their path southwards. But it doesn’t happen on its own, just because of family ties. There are larger forces at work that enable the situation.

Underpinning this activity is national expansion and Native dispossession, as during the first decades of 1800s, the US government instituted a policy of forcible removal of Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw and their enslaved people out of the Alabama, Georgia and Florida territories, known as the Trail of Tears. Parcels were drawn up, the land subdivided and sold off. Like many families from the Middle Atlantic states of Virginia, North and South Carolina, members of the Williams family were early investors in the expansion of cotton plantations in the deep South, and arrived in Alabama in the early 1820s.

Darlington, South Carolina

I called the Call County Courthouse in Marengo, and they were surprised to learn of the films on FamilySearch. They mentioned a volume of inventories existed. From other Black ProGen members, I learned these films were not necessarily comprehensive. The clerk at the courthouse suggested I contact the Darlington County Historical & Genealogical Commission, as they had some of the older court papers there. This was a game changer.

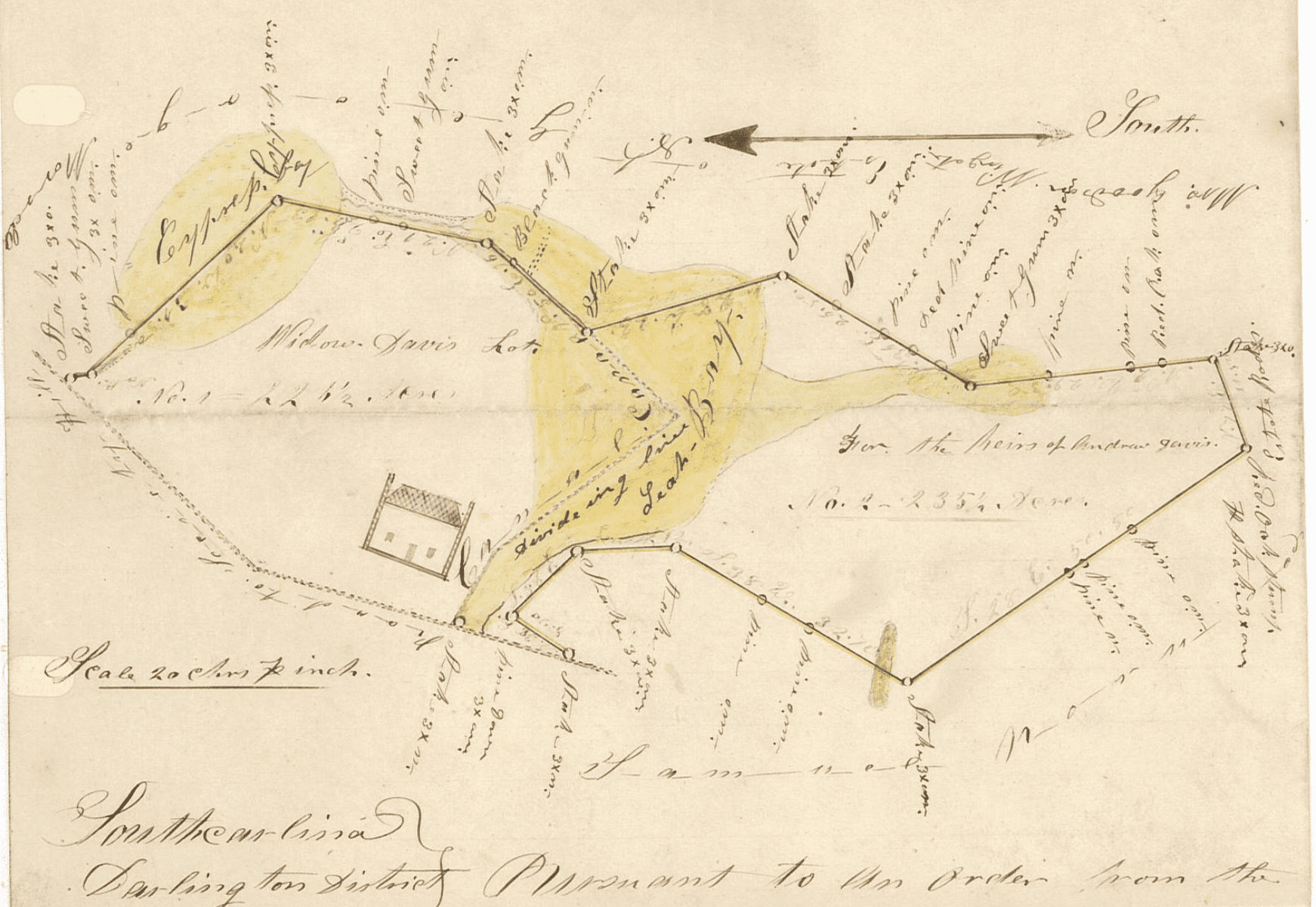

There was indeed a packet of estate papers for William Williams, who died intestate. Ms. Anne Chapman, the Assistant Director searched and located the documents. What was interesting was the early subdivision of human and material property by Davis in-laws in the Equity Packets dated 1849. There are some 60 pages in two packets. About 4 pages includes the names of men, women and children apportioned to family members.

What I learned from one document was that the Andrew Davis of these pages with the recently widowed Martha Davis, were the parents of at least three Davis sisters– Elizabeth Davis Williams, wife of Ashley Williams being one of them. This family was not one researched broadly nor in any Ancestry trees, with Elizabeth’s 1829 birth date added without any parents listed. Also, a quick search reveals nothing about the family in local histories, making tracing them a bit more difficult. Just one probate document made these family relationships clear, showing just how important court documents can be for reconstructing family ties.

Enslavement as a Familial Affair: Understanding patterns of subdivision and generational trauma

One page I transcribed listed several people, and included was a Writ of Partition dated 13 July 1860 that names Elizabeth Davis Williams’ two sisters, Martha Davis Dalrymple and Susana Davis. There was also a separate page for “An Inventory and Appraisement of the Goods & Chattel” belonging to the Estate of Andrew Davis, dated 4 Nov 1845.

Negro Ned 475

“ Jim 500

“ Mackey 250.00

“ Elvey —

“ Lanie — 600.00 [3 together]

“ Sam —

“ Pat 365.00

“ Ann 425.00

“ Bill 350.00

“ Ben 250.00

“ Anthony 150.00

“ Jinery 325.00

“ Charlotte & 500.00 [2 together]

“ Mariah —

Mules 5000

Equity Packet No. 166 p. 8, Courtesy Darlington Historical & Genealogical Commission, Darlington, SC.

These documents show that slavery was very much a family affair, a familial process along which one family gains income from the lives of people deemed other. The valuation of the enslaved is coolly noted, and provides a trail to follow for where they wound up next.

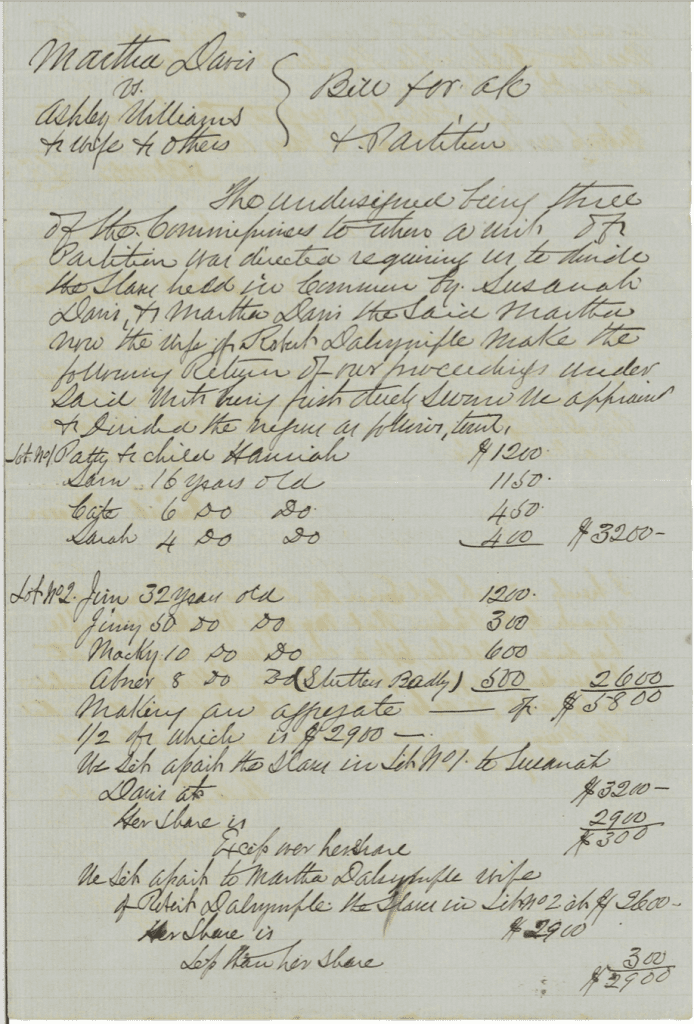

Writ of Partition

Martha Davis

vs – Bill for o/c & Partition

Ashley Williams

& wife & others

The undersigned being three or the Commplices to where a writ of Partition was directed requiring in to divide the Slaves held in common by Susanah Davis & Martha Davis the Said Martha now the wife of Robert Dalrymple Make the following return of our proceedings under said with being first duel Swore the appraised & divided the Negroes as follows, to wit,

Lot no 1/ Patty & child Hannah $1200

Sam 16 years old 1150

Cate 6 Do. Do. 450

Sarah 4 Do. Do, 400 $3200

Lot No.2/ Jim 32 years old 1200

Jiney 50 Do. Do. 300

Macky 10 Do. Do. 600

Abner 8 Do. Do. (Stutters badly) 500 $2600

Making an aggregate —— of $5800

½ of which is $2900 —

We set apart the Slaves in Lot No 1 to Susanna

Davis at $3200

Her share is 2900

Except her share $ 300

We set apart to Martha Darywimple wife

of Robert Darywimple the Slaves in Lot No 2 at $2600

Her share is 2900

Less than her share 300

$2900

Although you can read this document, it will not tell you of the emotional weight and profound stress of an impending split brought on by a Writ of Partition that subdivides family into Lots. There’s a contrast between the economic abstraction and what Daina Ramey Berry called ‘soul value’ that enslaved people held onto despite the dehumanizing conditions. For the sales, Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul: Life in the Antebellum Slave Market offers a glimpse into the process of selling the enslaved at auctions.

These two Davis inventories were recorded over several years– the first taken in November 1845, the second in January 1860- fifteen years apart. It provides some key information- ages that will help in searching for them. While Anderson and Nelly do not appear here, there are the names of people who lived with Elizabeth Davis’ mother and sister. It will take time, and I’ll continue posting transcriptions as I wend my way through the documentation.

These weren’t the only persons involved. On p.42 of the Will Book vol 8-10 on Ancestry’s South Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1670-1980 [database on-line] , for Andrew Davis’s estate in 1848, an order for the sale of Ned, household property, animals and crop was set for that December. Ned appears first on the list for the Writ of Partition of 1845, and next the offer of sale. What happened to Ned after December 1848?

I’m still in the process of piecing together the remainder of documents that overlap, some from the Darlington County Historical and Genealogical Commission, others from the Will Books on FamilySearch and Ancestry. While I didn’t find Anderson or Nellie Williams, what was gained is a better sense of the community of people split asunder by what we can read today as another family’s sense of white privilege, economic gain and a fundamental blindness to equality.

To be continued…