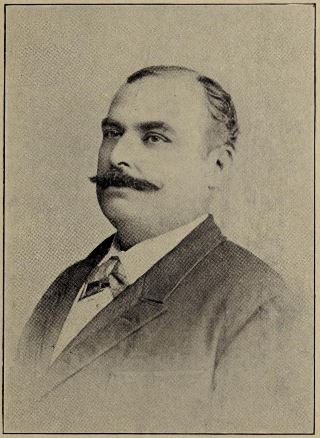

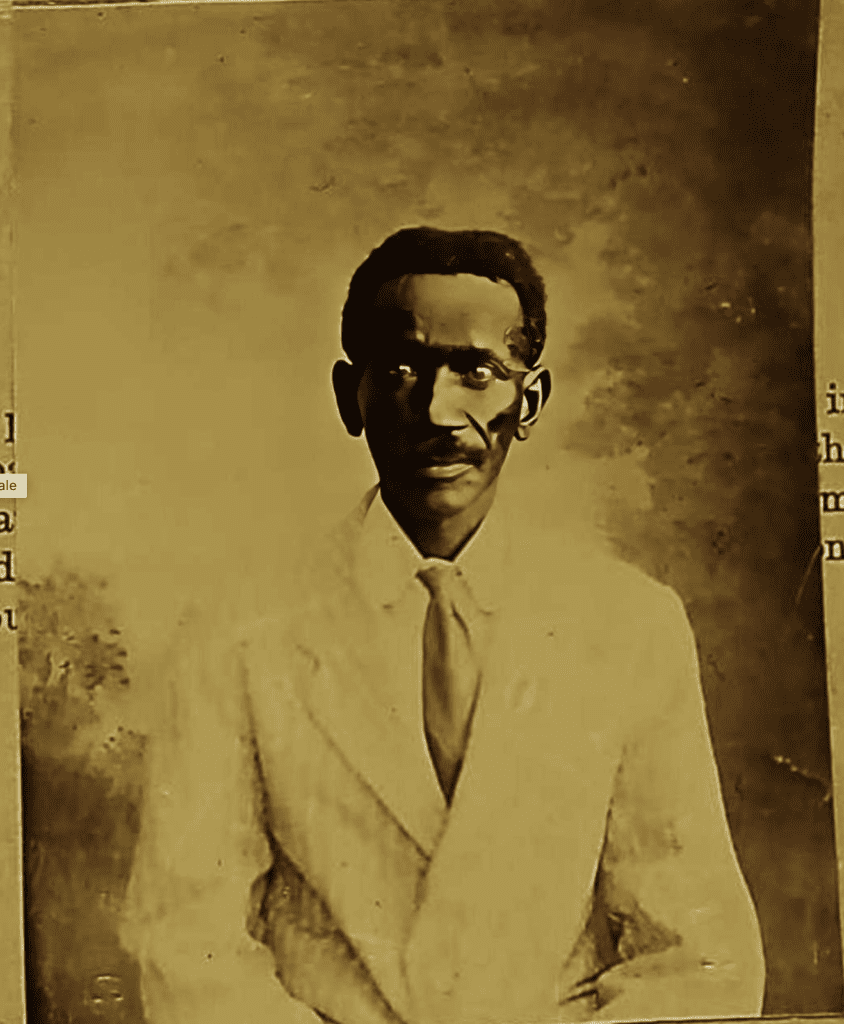

A few weeks ago, I saw a hint on my Ancestry family tree for Estevan Vale Caban. To my great surprise, it included a photograph! Could it be my great uncle?

After finally locating the origin of a foto for Estevan Vale in Ancestry’s Passports database, I was struck by how much of a desire there is for an image of an ancestor. For some apparently, this desire was so strong, it overrode taking a closer look at the pages for the record the photograph came from. Yet I learned more about another branch of my family by searching for more on him.

Estevan Vale: dapper & traveling

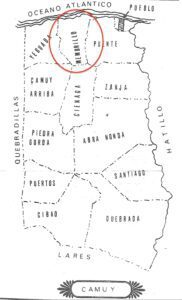

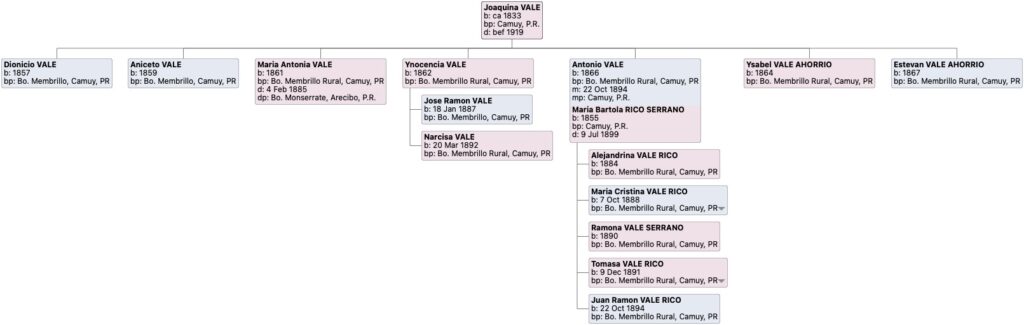

Estevan Vale was born on Christmas Day, 1867, in Barrio Membrillo, Camuy, the son of Joaquina Vale. She is alive around 1892, when his brother’s grandchildren were born. Her death record remains unlocated,. It seems as though she evaded the pages of the Registro Civil, yet by chance, she is mentioned in her children’s records.

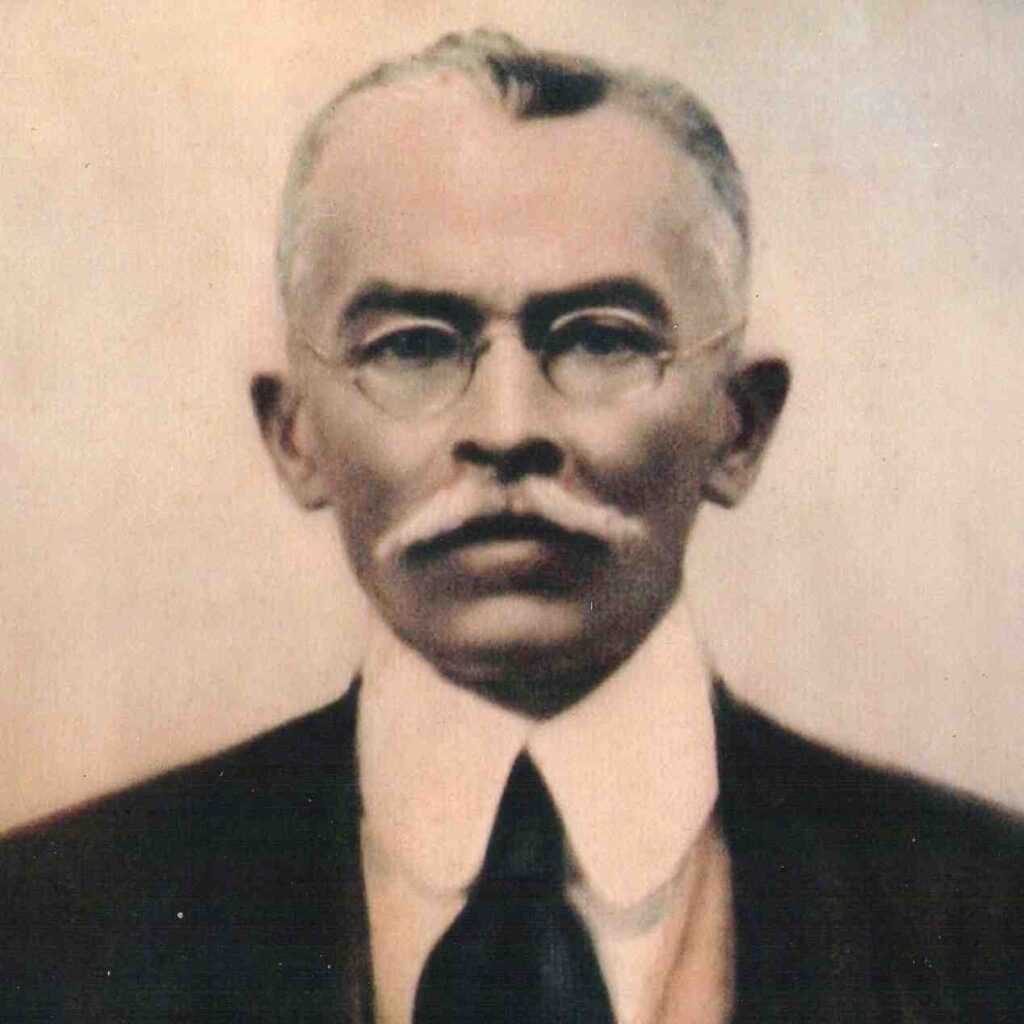

The photograph shows a seated dark skinned man with tight hair in a white shirt, light striped double breasted jacket and contrasting satin tie. The fact of his style and the tie dates the photograph to the early decades of the 1900s. His eyes are unusual. He appears to be staring because of the flash bulb used to take the photo, as his eye color is listed as black. His gaze takes in every detail as he moves between nations. He planned to go under an agricultural permit to Cuba, sailing on the Santiago de Cuba out of Ponce sometime in October 1919. He signed the document with his mark on 27 September 1919.

In order to find out more, my search broadened timewise, and I began by looking for him and his mother, Joaquina Vale, who is mentioned in the document.

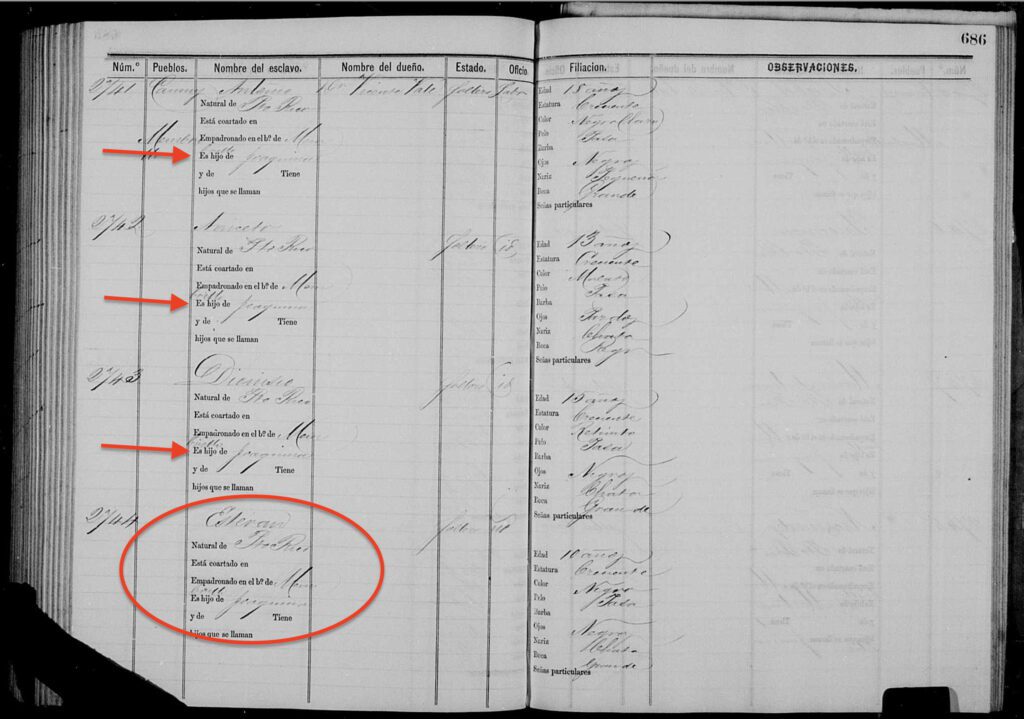

Joaquina’s children: Camuy, 1872

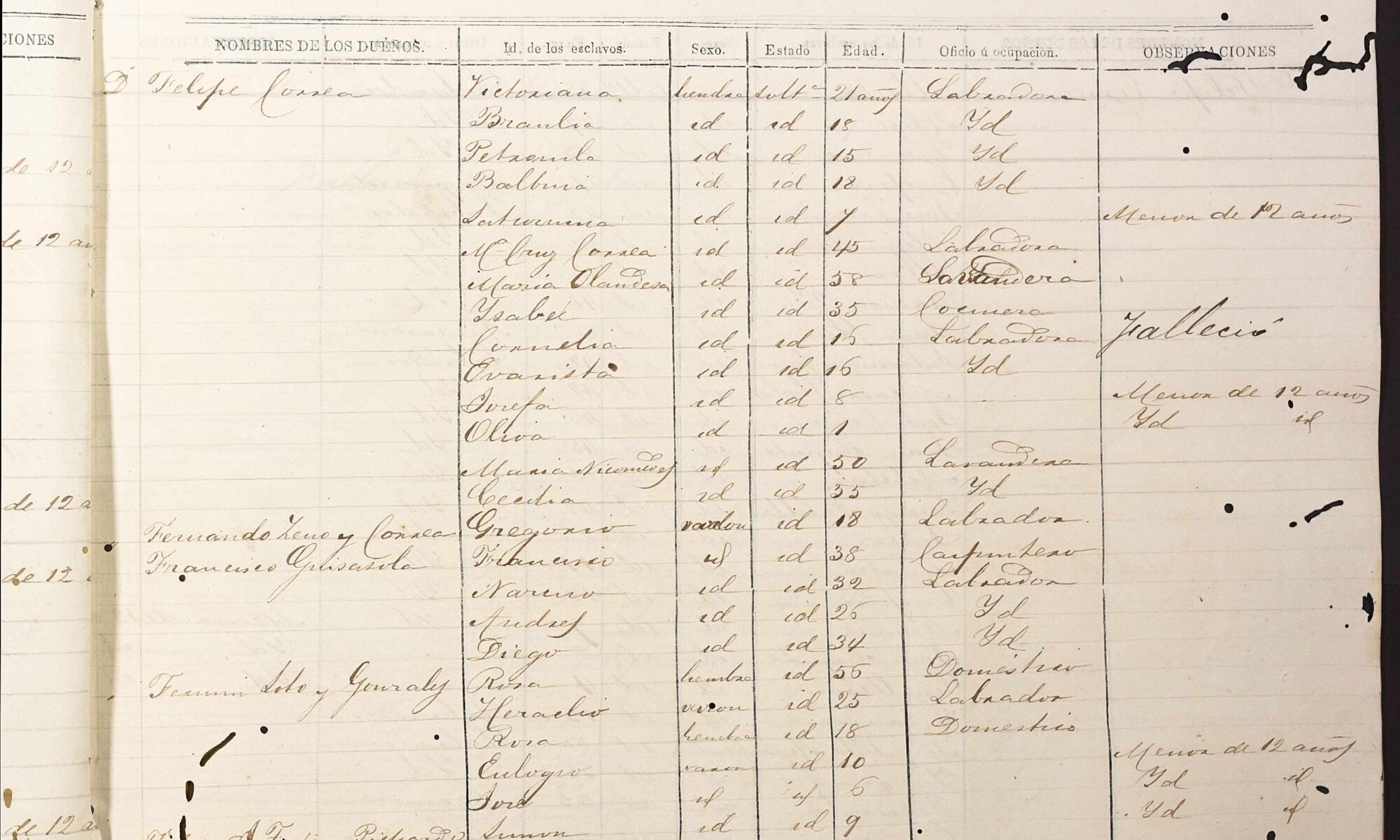

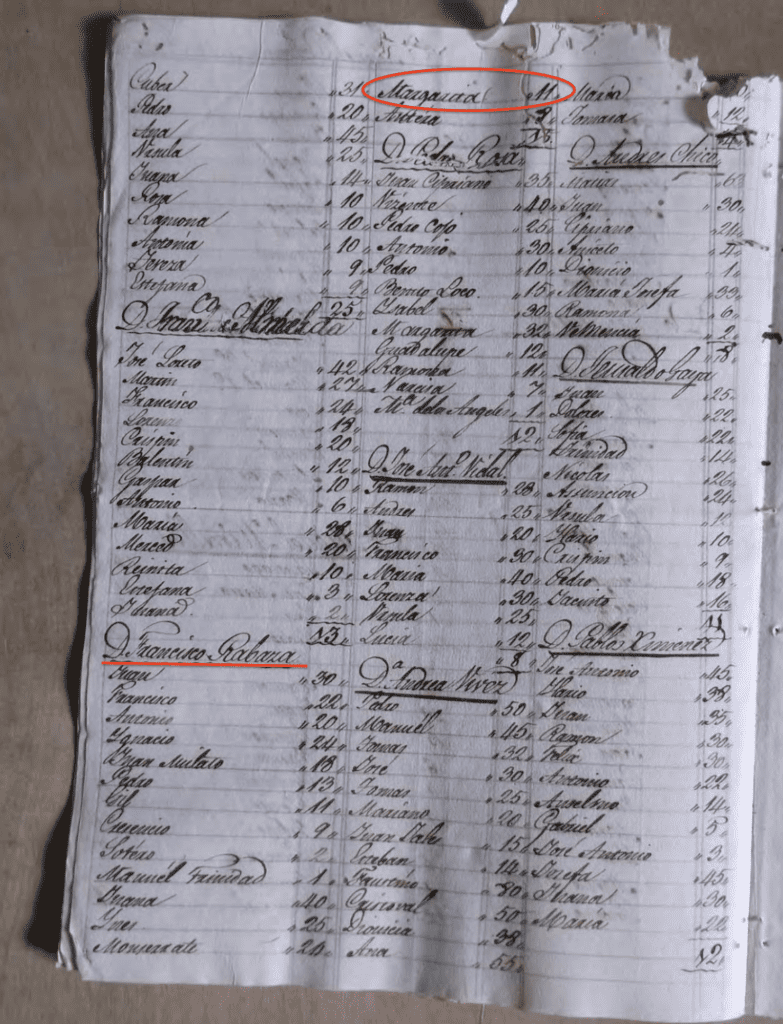

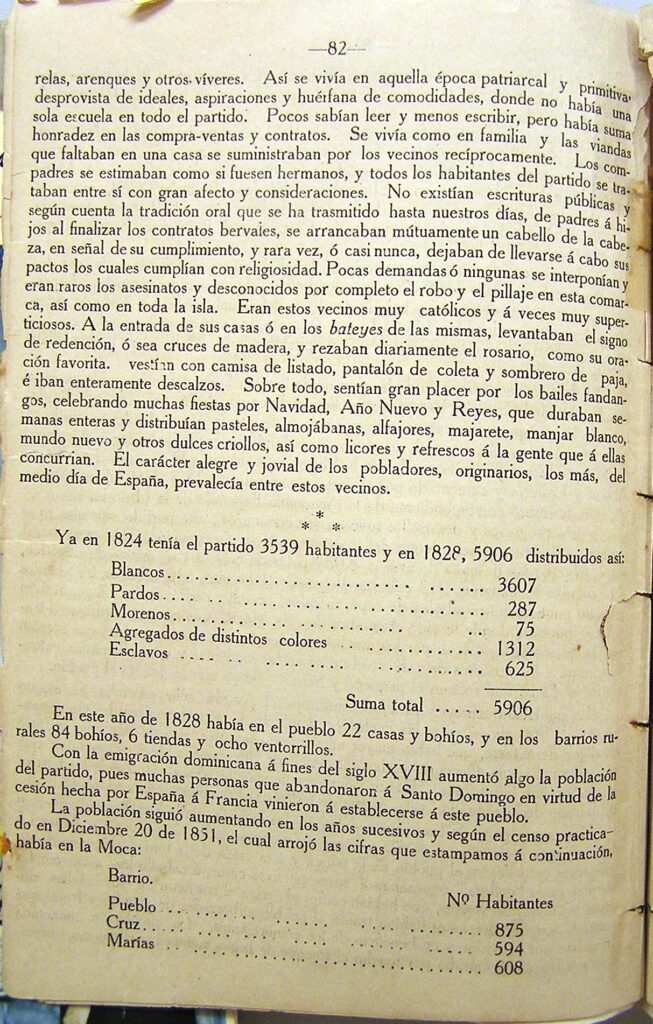

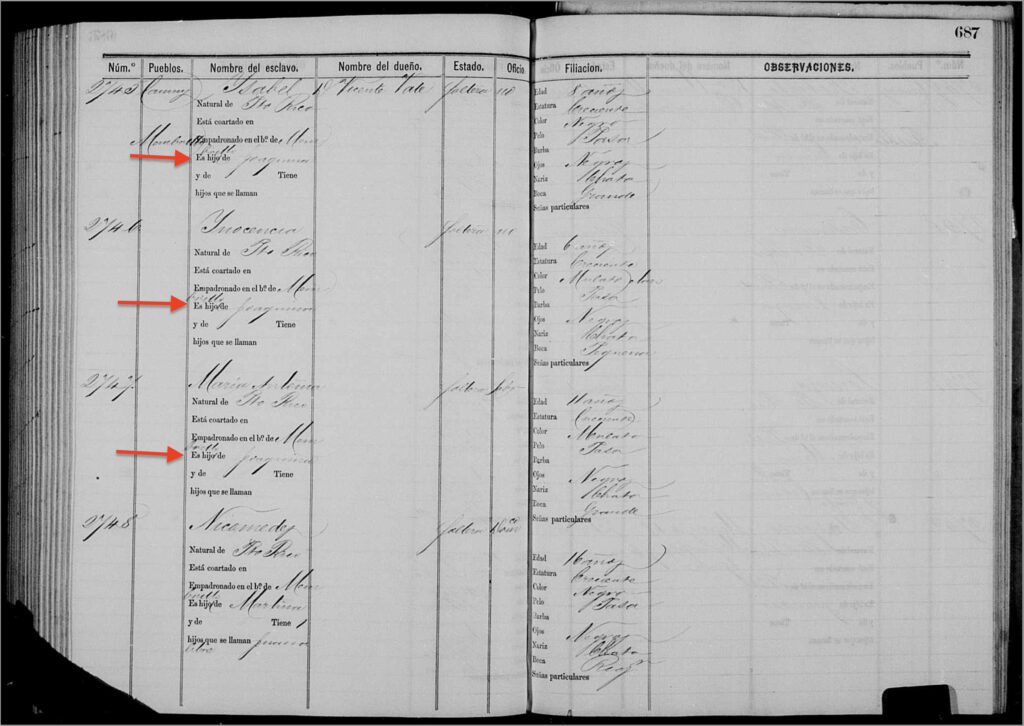

There, across two pages of the 1872 Registro Central de Esclavos for Camuy appear the seven children of Joaquina, all of them enslaved by Vincente Vale Caban (b. 1806, Moca-d. 1889 Camuy ) : Antonio 18, Aniceto 13, Dionicio 14, Ysabel 8, Ynocencia 6, Maria Antonia 11, and the last child on the first page– 10 year old Estevan. Aside from Joaquina’s children, there’s only 16 year old Nicomedes, the son of Martina who is also recorded as held by Vicente Vale in Barrio Membrillo, Camuy.

JOAQUINA’S CHILDREN: Ysabel, Ynoncencia, Maria Antonia, 1872 Registro de Esclavos, Camuy. FamilySearch

Vicente Vale Caban, Barrio Membrillo

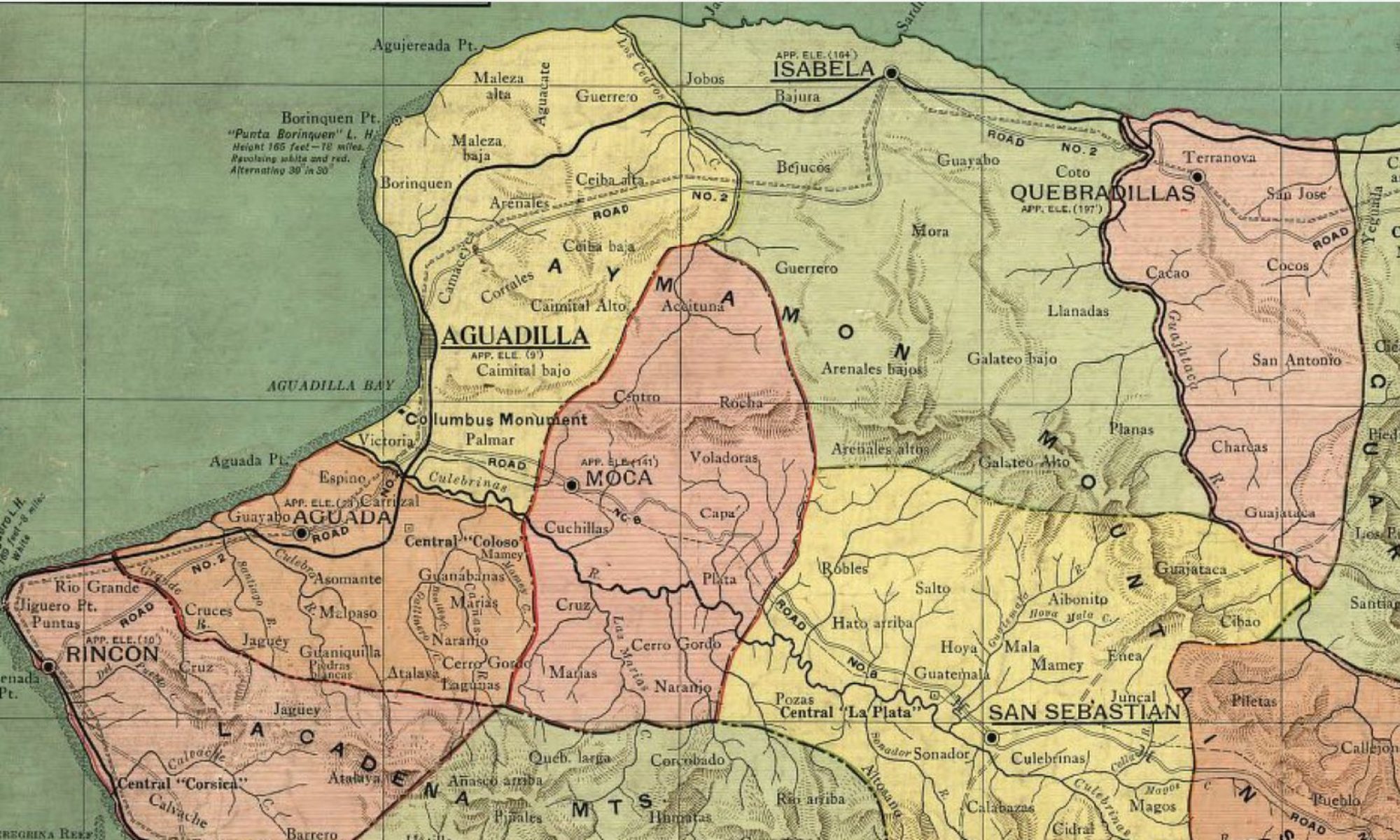

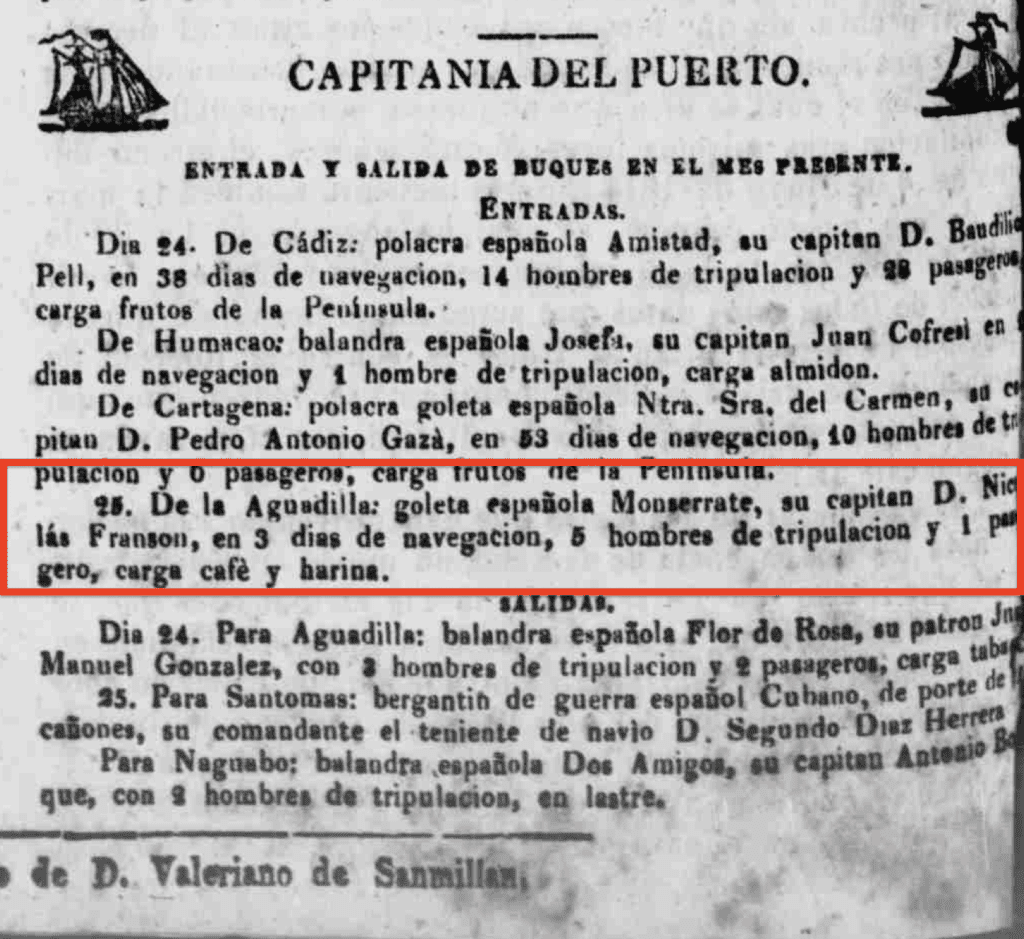

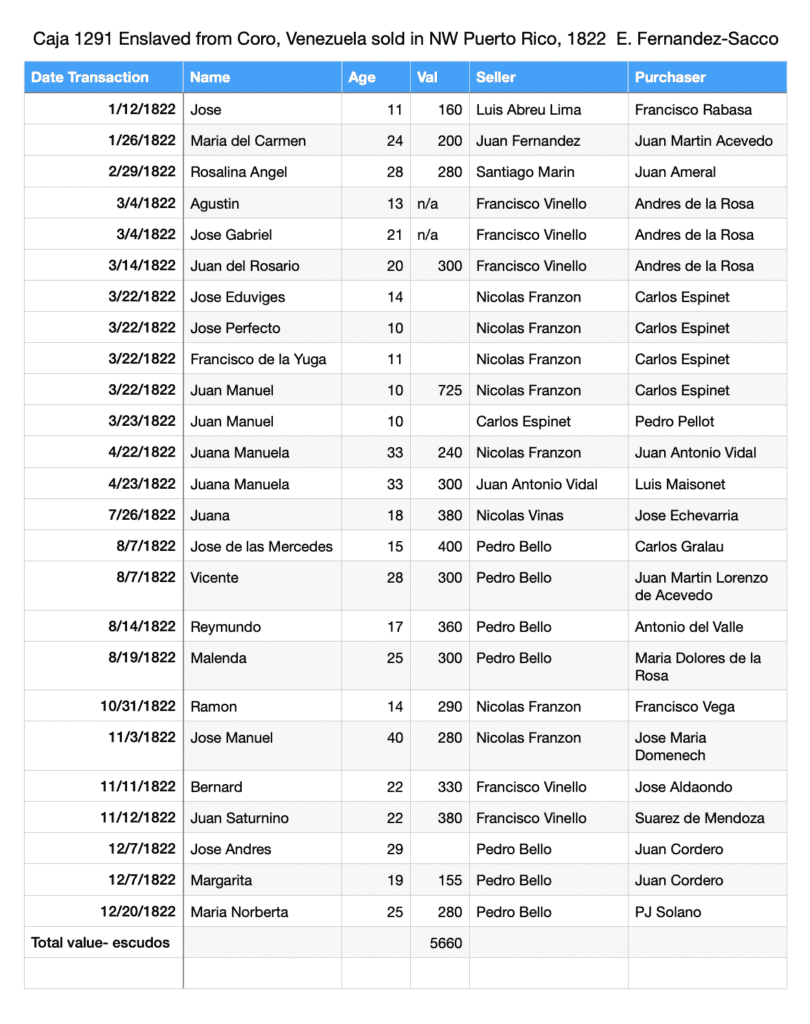

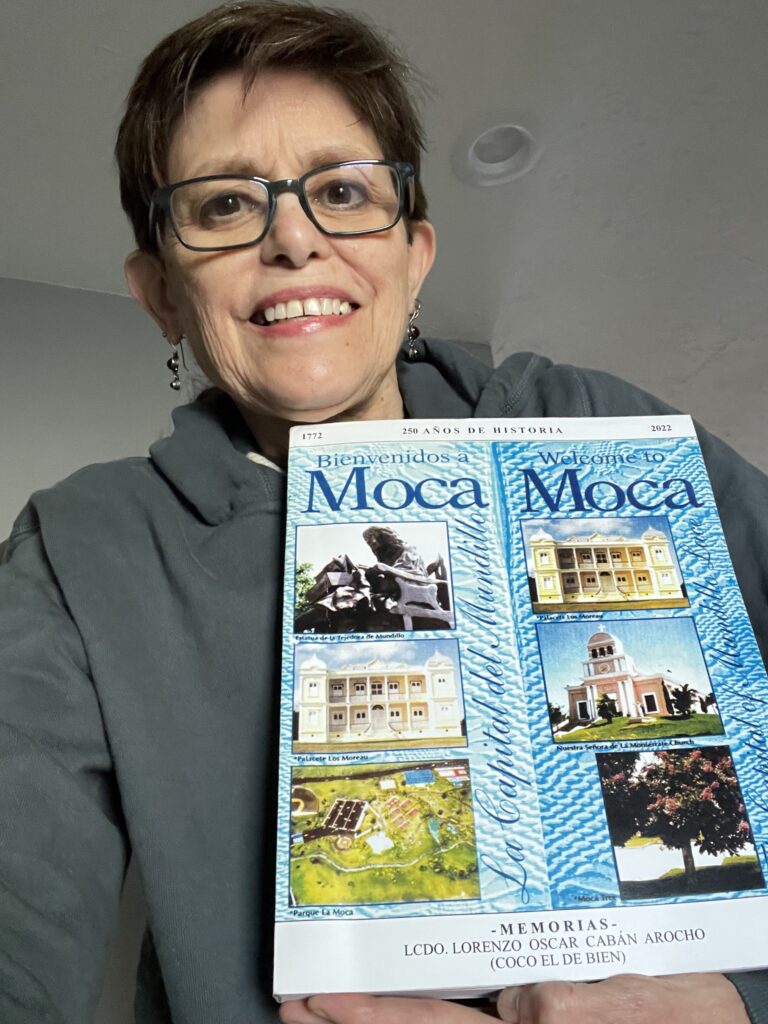

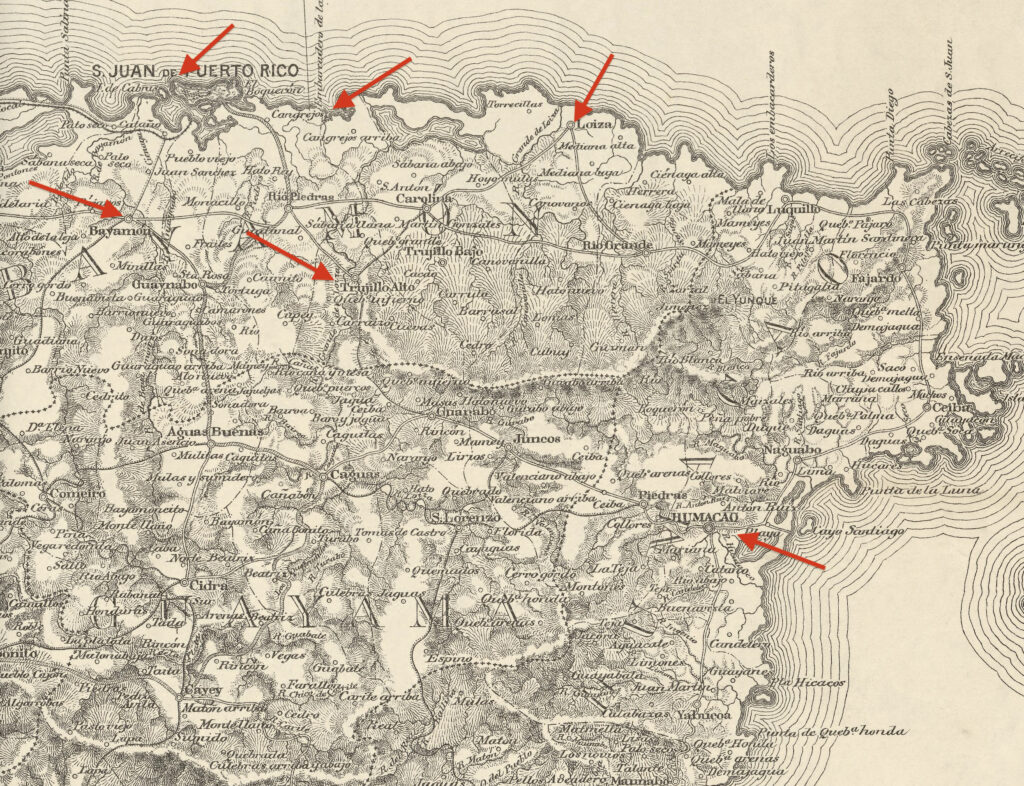

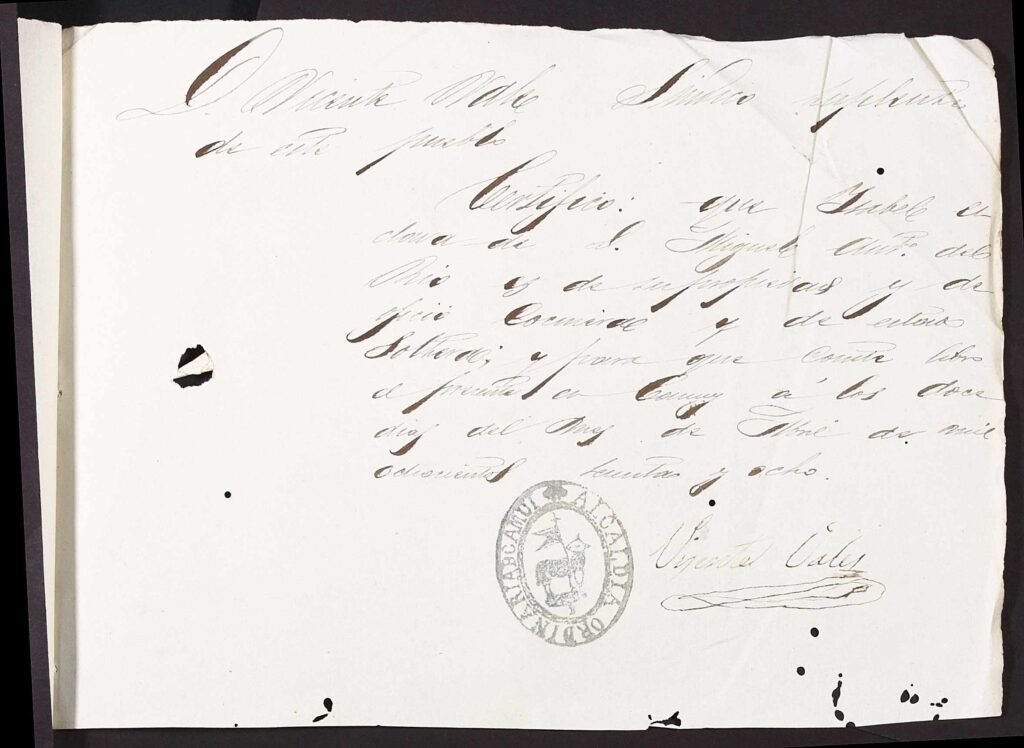

Vicente Vale Caban is my second great grand uncle, and I was unaware of enslavers on the Vale line until now. In part, that was because he lived not where most Vale lived, in Moca or Aguadilla, but in Camuy’s Barrio Membrillo, a different district. How he wound up there doesn’t have a concrete answer at the moment, however, there was an exodus out of many municipalities during the 1820s and again by 1849, due to drought and other conditions. These Vale may appear on municipal documents or notarial documents that lend more details about their lives. Vicente Vale was an enslaver, and after the Moret Law and the administrative development of the Registro Central de Esclavos, Vale became a local official.

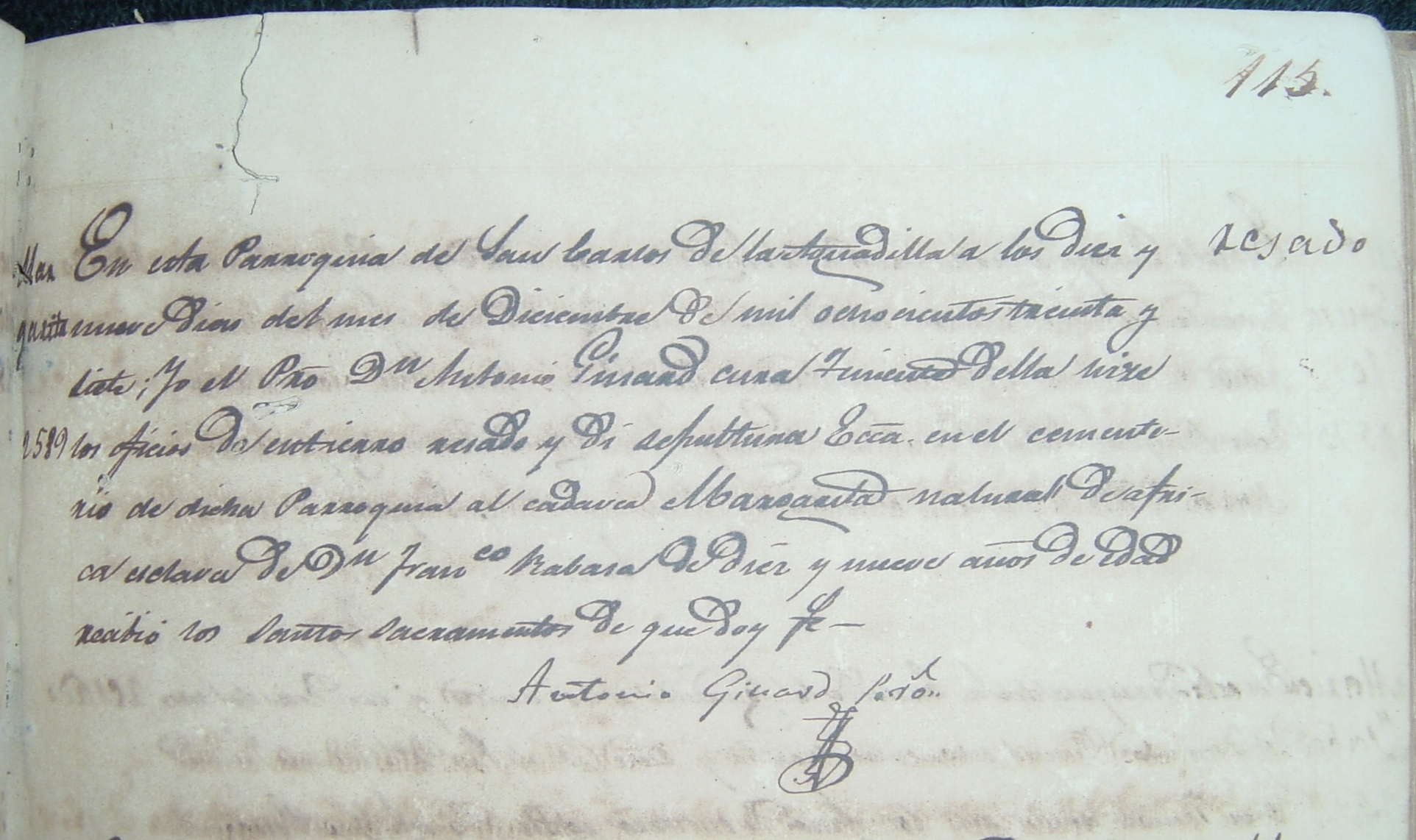

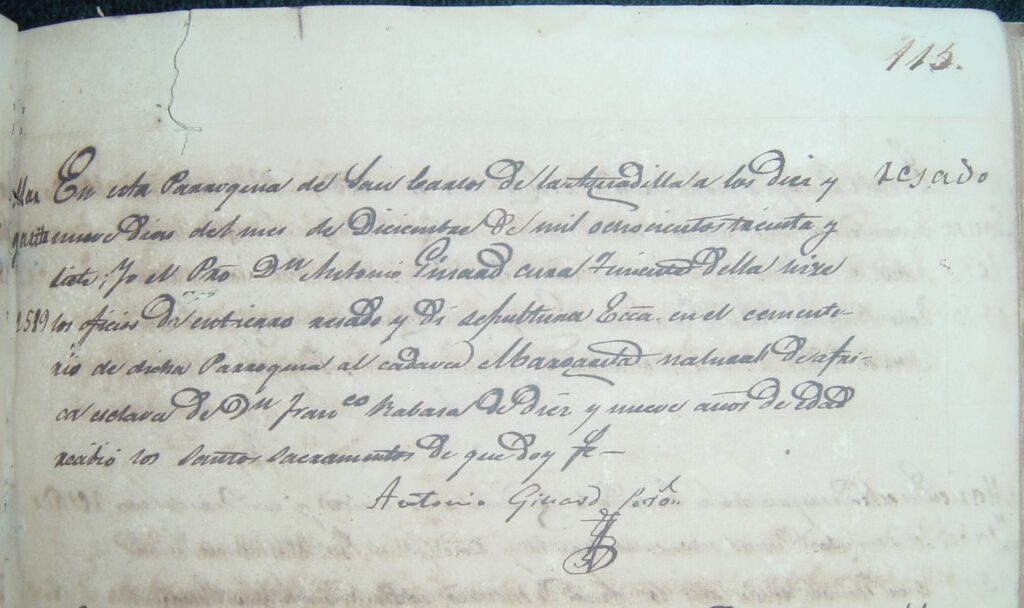

In the recent cluster of 865 sets of documents under the Gobierno de Puerto Rico that were uploaded to FamilySearch are four slips from 1868 signed and stamped by Vicente Vale as sindico suplente (substitute officer) of Camuy, verifying the identity and ownership of enslaved persons belonging to other enslavers. These documents supplemented the creation of cedulas (registration papers) for each person. Vale then, was employed by the Mayor’s office that sent documents to the Registro Central de Esclavos. I’m currently looking for more information about that post.

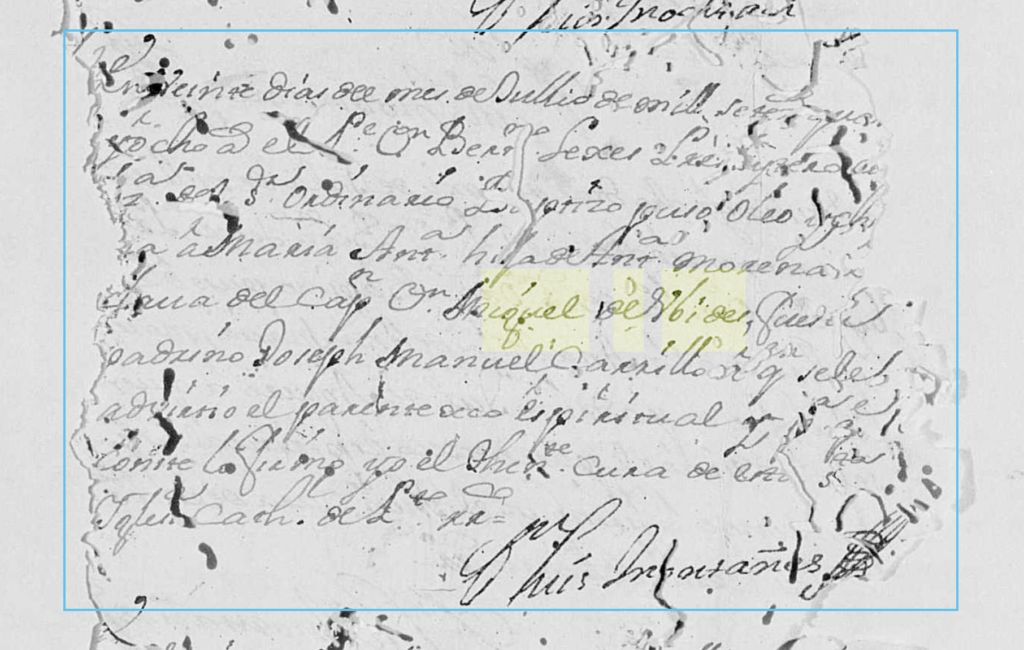

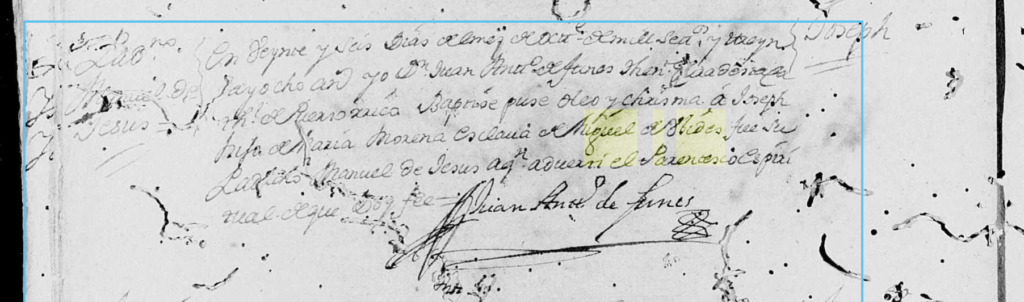

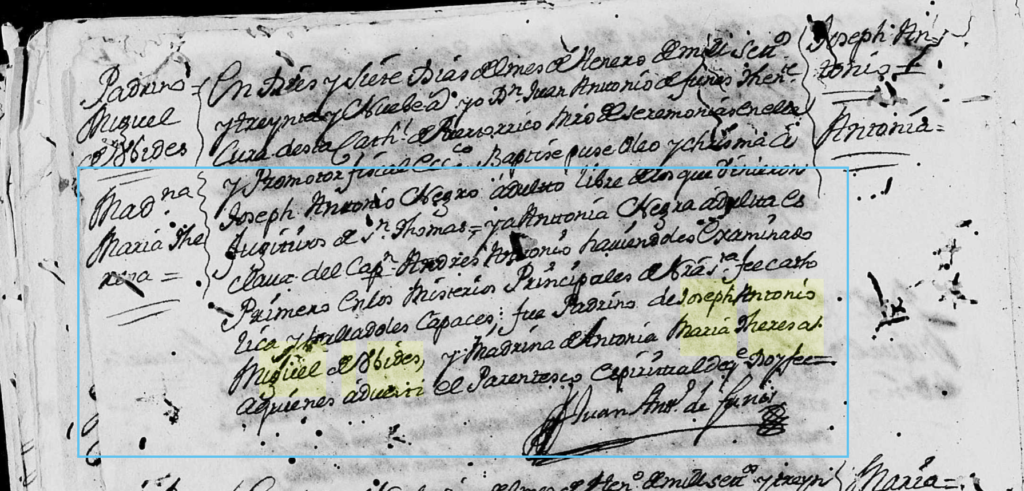

Vicente Vale Sindico suplente de este pueblo. Certifico que Ysabel, esclava de D. Miguel del Rio y de su propiedad y de oficio cocinera, y de estado soltera, y para que consta libro el presente en Camuy a los doce días de Abril de mil ochocientos sesenta y ocho. [Firma] Vicente Vales, Alcaldía Ordinaria, Camuy. FamilySearch https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-WQ1C-43PY-B?view=explore

What’s odd is that while Vale family appears in the 1872 Registro Central de Esclavos volume that includes Anasco, they are not among the individual 1868 cedulas for Anasco- apparently the set of cedulas are incomplete.

We know that Joaquina is criolla, born into enslavement on Puerto Rico. So far, Joaquina’s children decided to take on the Vale surname after emancipation. Where exactly they labored in Vale’s farm or home, isn’t specified beyond a barrio, and will need more research to locate.

The Vale Family in Census Records

By 1930, Esteban’s sister Tomasa Vale lived next door to her sister Maria Antonia Vale Rico; both women left Barrio Membrillo and moved to the San Juan area to increase their chances for work. Tomasa Vale supported her household by working as a lavandera on calle Martin Pena Chanel in Santurce. Cristina lives with her second husband, Felix Ortiz Ortiz. Also with the couple are her three children. She worked as a planchadora, an ironer, so it’s possible the sisters shared a business, or worked independently in the service industry.

In the 1940 US Federal Census for Camuy, Estevan, now 80 years old and his sister Ysabel Vale are in the household of Pedro Maldonado y Camacho and Emilia Gonzalez. They are listed as ‘tio‘ and ‘tia‘ respectively. The siblings appear with the maternal surname of Ahorrio, which may be a strategy to acknowledge their paternal lineage, safely used decades after their birth. Often this use comes up long after a father made his transition, so there is no familial repercussion.

The detail that tells us something about Joaquina is in the relationship to the head of household listed– Estevan and Ysabel are aunt and uncle to Pedro Maldonado Camacho. This suggests that Joaquina used Camacho, or perhaps had a partner with the surname. when looking at Pedro’s half sister, Ynocencia Vale Camacho, her death record has her father as Ramon Vales (bca 1827) and mother as Joaquina Camacho. Yet no records for Ramon beyond this entry turns up- or was he actually Ramon Camacho? This Ynocencia is may or may not be the same Ynocencia that appears on the pages of the 1872 Registro, with listed as the daughter of Joaquina. Another death record for Leon Camacho (1853-1923) of Camuy lists only his mother, Joaquina Camacho.

At the very least, Joaquina had seven children between 1857 and 1867; she herself appears on no cedulas, suggesting that she may have already obtained her freedom. In her grandson’s birth certificate she is referenced as ‘Joaquina Vale Liberta’, as is her son, ‘Antonio Vale liberto sin segundo apellido’. Yet by appending liberto, the municipal government calls out a status that supposedly ended in 1876, when the emancipated also became full citizens. Maria Cristina Vale Rico’s Acta de Nacimiento was filed in October 1888.

May we learn more about the struggle & resilience of these ancestors.

References

Esteban Vale, No. 5330, 7 Oct 1919. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: U.S. Passport Applications, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Philippines, 1907-1925; Volume #: Volume 24: Passport Applications- Puerto Rico. Ancestry.com. U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2007. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1174/records/2314650?tid=&pid=&queryId=135e671f-c092-46ae-9f31-787481ca2bca&_phsrc=rHz1&_phstart=successSource

Children of Joaquina, “Puerto Rico records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSV2-K76P-8?view=index : Mar 20, 2025), image 114 of 130;

Ysabel, “Arecibo, Puerto Rico records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-WQ1C-43PY-B?view=explore : Mar 20, 2025), image 11 of 147; .

“Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2002”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJ4-ZRFL : Tue Mar 11 20:12:35 UTC 2025), Entry for Inocencia Vales Camacho and Ramon Vales, 26 Jul 1938.

“Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2002”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJ4-Z34R : Tue Mar 11 14:13:47 UTC 2025), Entry for León Camacho and Joaquina Camacho, 13 4 1923.

“Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2002”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJ7-HK7X : Tue Mar 11 03:27:36 UTC 2025), Entry for Maria Cristina Vale y Rico and Antonio Valez Liberto.