Finding additional details can make working with documents fascinating. Often it can help us understand relationships that structured the lives of persons further back in time.

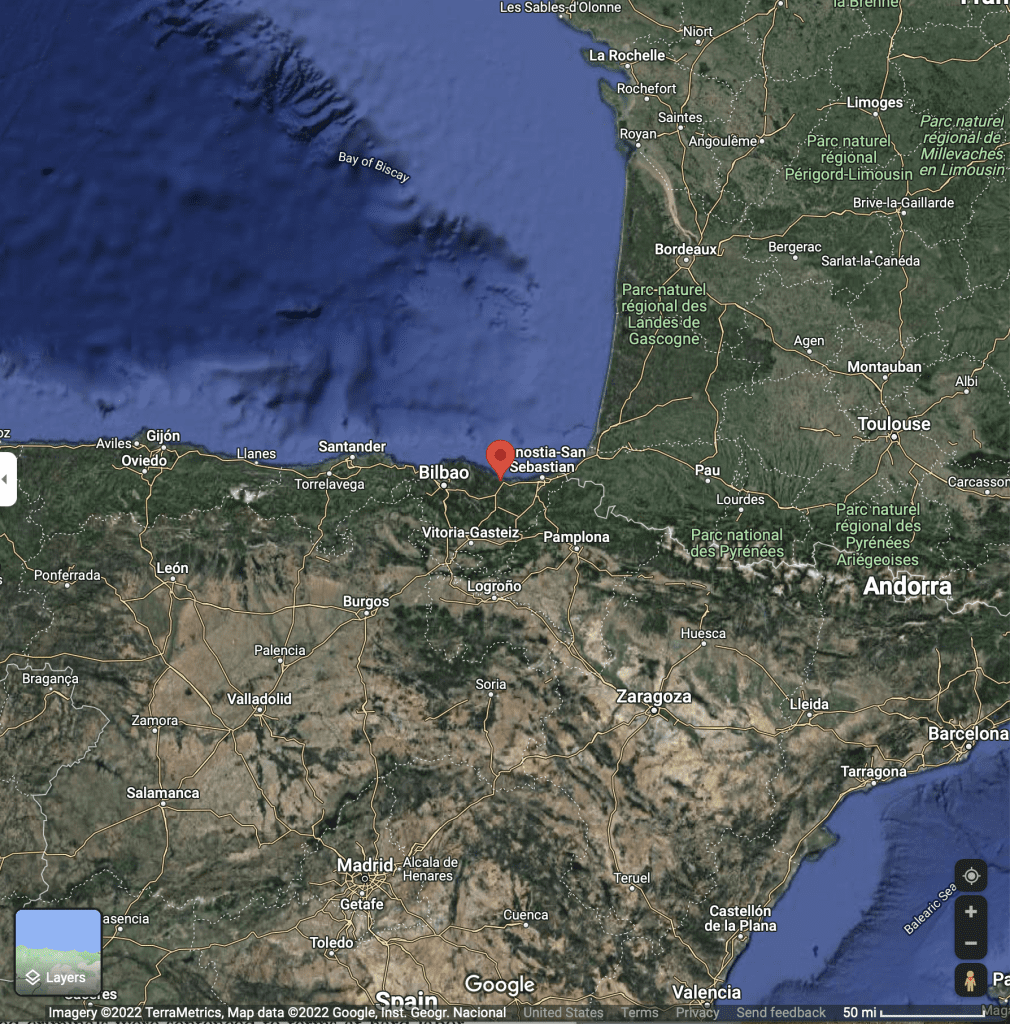

Some collateral lines have ancestors who came from sites in Spain, details that are often reduced to “Espana”. The Yturrinos (or Iturrinos) offer another connection to Basque country, and this family is from an old coastal port town, today called Mutriku (Motrico) in Guipuzcoa founded in 1209. Why come so far?

Of Whales, Fish & Indigenous People, De Balenas, Pescados y Gente Indigena

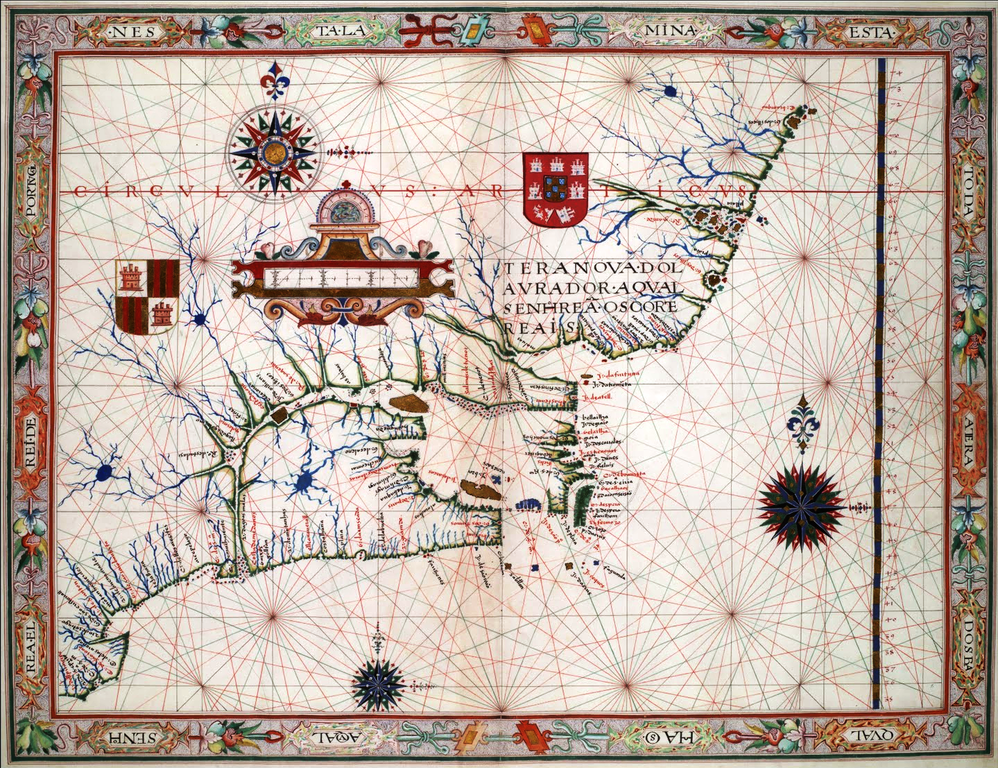

People have sailed out of Mutriku for centuries. Historian Birgit Sonneson writes that since the Middle Ages in Basque country ports, the activities of fishing and maritime traffic were the economic base for the region. In fact, Basque whalers and fishermen went to Canada yearly to fish whale and cod, an interaction that had the fishermen learning Indigenous words from the local groups.

Champlain’s journals contain Basque words. There were no permanent Basque settlements, but camps along the coast were occupied by the fishermen from April to September when they departed for home. [1] By 1541, several Iroquoian groups already had Basque names by the time the French arrived in Labrador. The industry lasted until 1579 when the English attacked Basque whalers. This created a crisis that ended their whaling in the Strait of Belle Isle . [2]

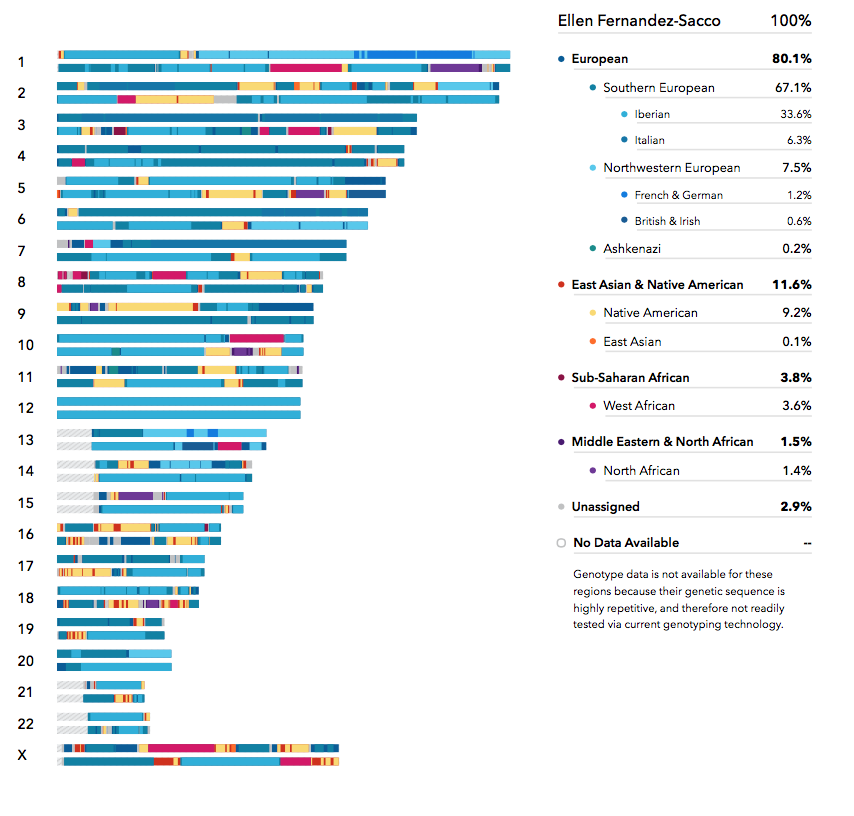

That may have ended whaling as an industry, but the Basque regrouped and focused on fishing, sealed and traded with Indigenous peoples and sedentary fishing communities. They laid claim to more than 100 ports throughout western and southern Newfoundland, Cape Breton Island, Chaleur Bay, and the St. Lawrence Estuary. Historian Brad Lowen writes: “An indirect indicator of these partnerships is the historical incidence of Basque names among Inuit, Mi’kmaw, and Métis families in southern Labrador, Cape Breton Island, and parts of Gaspésie. ” Basques also forged ties with the Inuit around the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. [3] I imagine there are blended ancestries reflected in DNA, another set of unexpected connections facilitated by colonialism.

Salt Cod

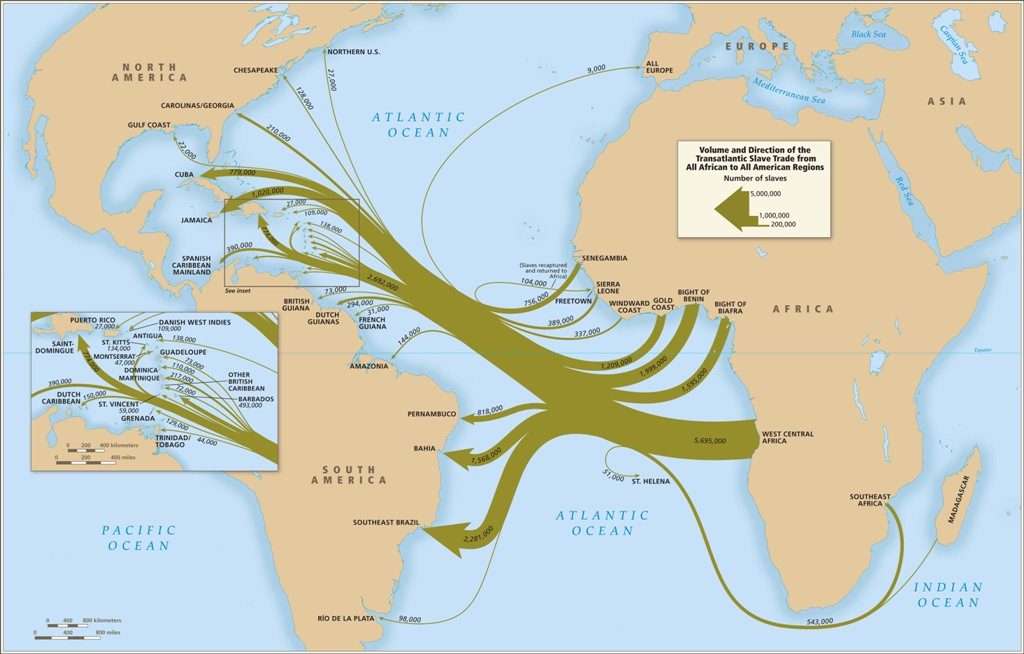

When John Cabot rediscovered Newfoundland in 1497, he saw the profit to be made from the fish in these cold Atlantic waters. Slices of cod were packed between layers of salt, and the water content dropped to 60%; with further drying, it went down to 40%. Now, this was a product that could last over the course of a long voyage, and without refrigeration. Demand on the Iberian peninsula and in European markets was high. By 1660, production increased, but what really drove demand in the late 17th century was the rise of sugar.

The increase in enslaved West Africans as labor for the production of sugar cane in the Caribbean made bacalao attractive to plantation owners that relied on cost-cutting solutions to make their profit. They bought cheap salt cod rather than devote large portions of land for growing crops or raising animals to feed the enslaved.[4] Those who prepared the small salt cod sold in the Caribbean were caught in a cycle of debt and credit. “El negocio del azucar es para Puerto Rico, lo que el bacalao es para Terranova.” [ 5]

The Yturrinos

I delved into this history of commerce in an attempt to get some clarity on what kind of ‘Comerciante‘ this Basque family member was part of. There were limits – as Mutriku is a port city, agriculture wasn’t an option to enter into, so it was either trade or fishing. With inheritance, only one son could inherit an estate, leaving the rest to fend for themselves.[6] As I have no correspondence or documentation on the first Yturrino to reach Puerto Rico beyond marriage and children, it’s difficult to say what precipitated the move across the Atlantic to the Caribbean. But as an island whose economy was then based on slavery, there are ties to this in some way.

The earliest known Yturrino in Puerto Rico is Juan Antonio Yturrino born in 1751 in Mutriku, Guipuzcoa. He is definitely on the island by 1780, when his son Pedro Joseph Yturrino Velez was born. Juan Antonio Yturrino married Rosalia Beles [Velez] Camacho, and she dies a widow by the time of her death on 13 Nov 1804, in Mayaguez.[7] They had five children, two of which have known descendants, Pedro Joseph born 28 Jun 1780 and Benito Iturrino Velez, born about 1792.[8]

Pedro Joseph Iturrino Velez married Ysidra Arzua Crespo of Bayamon. As far as is known they had one son, Felipe Iturrino Arzua. His brother, Benito Iturrino Velez was married twice, to Ysidra Morales Crespo on January 1814 in Anasco, and after her death, he married Catalina Martinez. [9]

Felipe Iturrino Arzua

On the morning of 16 March 1894, Felipe Yturrino Arzua died of fever at the age of 83. [10 ] His death record reveals a long life, with three marriages and children from each relationship, and substantial land purchases in Moca and San Sebastian. Born in Bayamon, he died in Barrio Corcobada, Anasco, and his family tree branches into several municipalities. Where it connects to my tree is through the Babilonia. Both his generation and those of the Babilonia Quinones were the grandchildren of at least one grandparent born in Spain, most often a grandfather.

These were marriages of equal social stature, that rested on an economy based on slavery, dependent on the labor of a highly admixed, African descended and Afro-Indigenous enslaved population. By the 1870s, this population transitioned to freedom about the time Felipe Iturrino began to have children. The plantations eventually became farms and after the Spanish American War were mostly dedicated to corporate sugar cultivation.

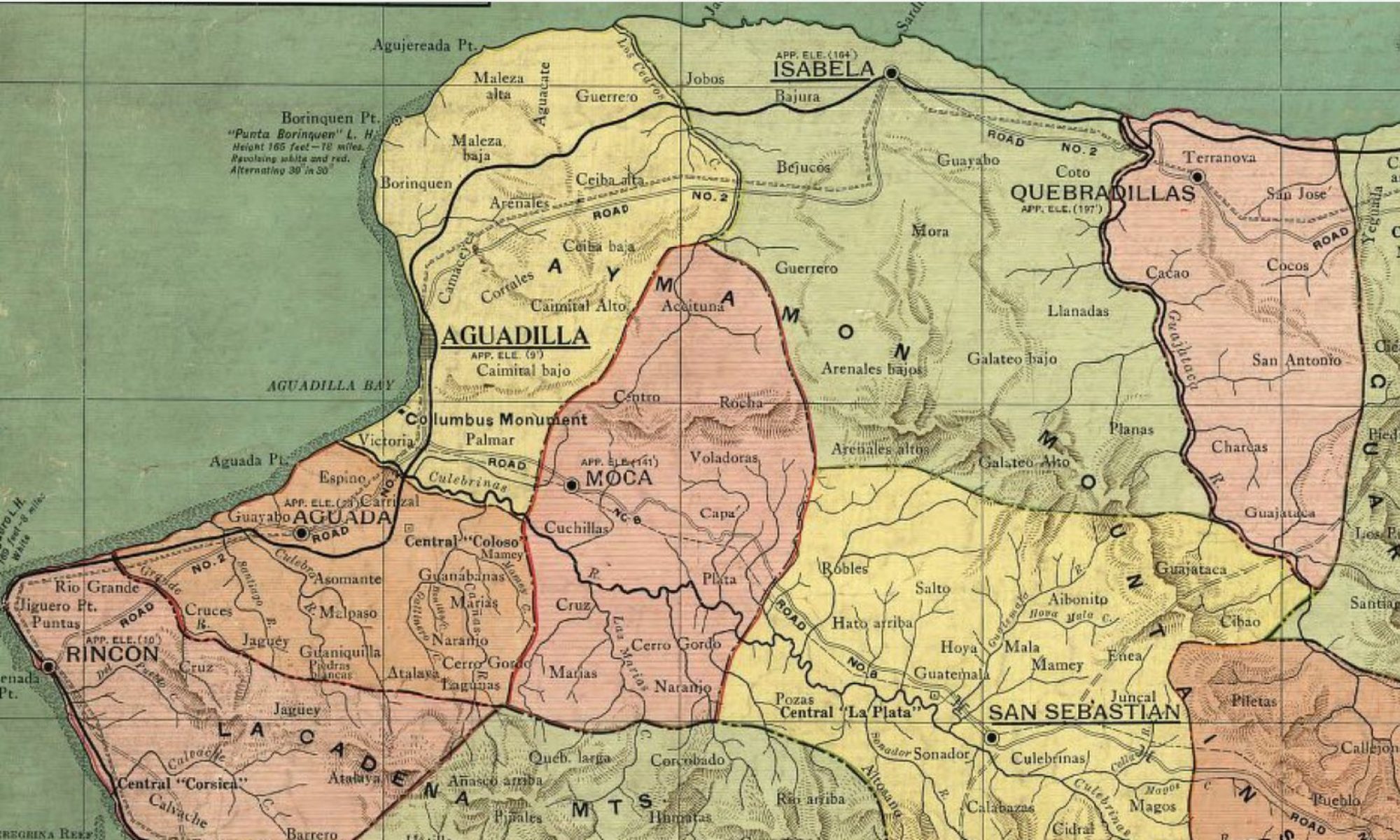

Land acquisition in Moca, 1864

In the 1860s, Felipe began purchasing land in Moca. In March 1864, he purchased over 23 acres of land that included coffee and coconut palm farms in Barrio Plata Moca from Jose Dolores Nunez. He received 386 pesos for it at the 1864 sale. This lot bordered property owned by Ramon Rivera on the south, Antonio Ramos on the east, and Flora Arocho on the north side. On the west side, his border was land embargoed by Nunez in lieu of payment. Nunez purchased the land over twenty years earlier from Cristobal Soto. [11]

Next, in August 1864, widow Florencia Acevedo of Moca went before the notary Eusebio de Arze in Aguadilla to register the sale of another adjoining piece of property in Barrio Plata to Felipe Yturrino. This property comprised over 21 acres in two lots, including pasture and brush (pasto y maleza) that bordered the previous purchase on the east side, and the embargoed land from Jose Dolores Nunez on the south. The smaller seven-acre lot ran along the land of Ramon de Rivera on the east, Manuel [illegible] on the west, and Manuel Hernandez to the south.

The plat’s borders were living– borders that extended from a variety of flowering trees and plants— guava, maguey, jobo, mamey, and moca, along with fresh water springs at different points. Florencia Acevedo Perez inherited this land from her parents Chrisosomos Acevedo and Antonia Perez, and sold it for 184 pesos. [12]

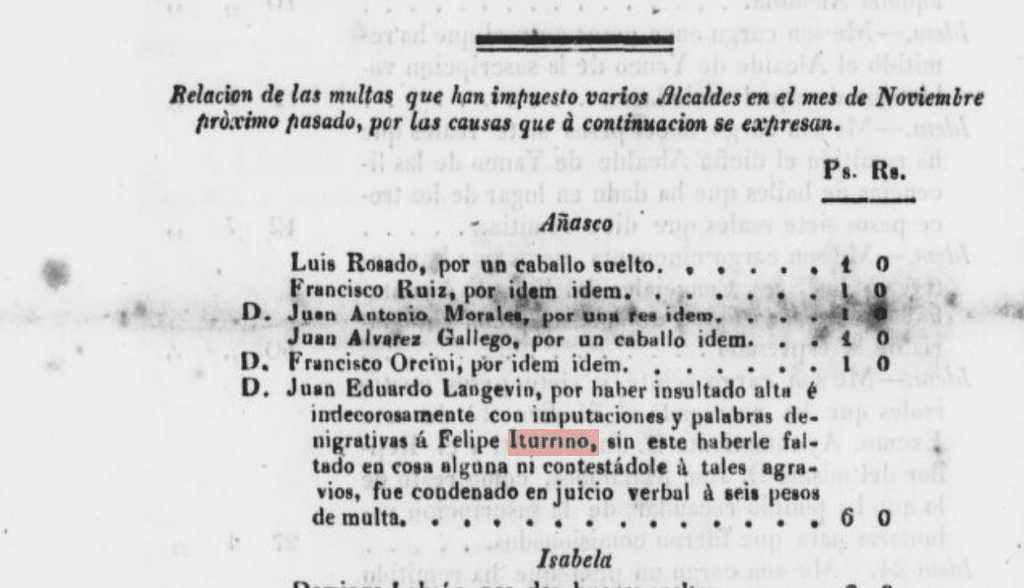

What kind of person was he? Felipe Yturrino didn’t take insults lightly, as this list of fines from January 1842 from La Gaceta shows. “D. Juan Eduardo Langevin for having loudly insulted with imputations and denigrating words to Felipe Iturrino, without him having lacked in anything or answering such grievances, was condemned in an oral hearing for a fine of 6 pesos .” [13]

The Marriages of Felipe Iturrino

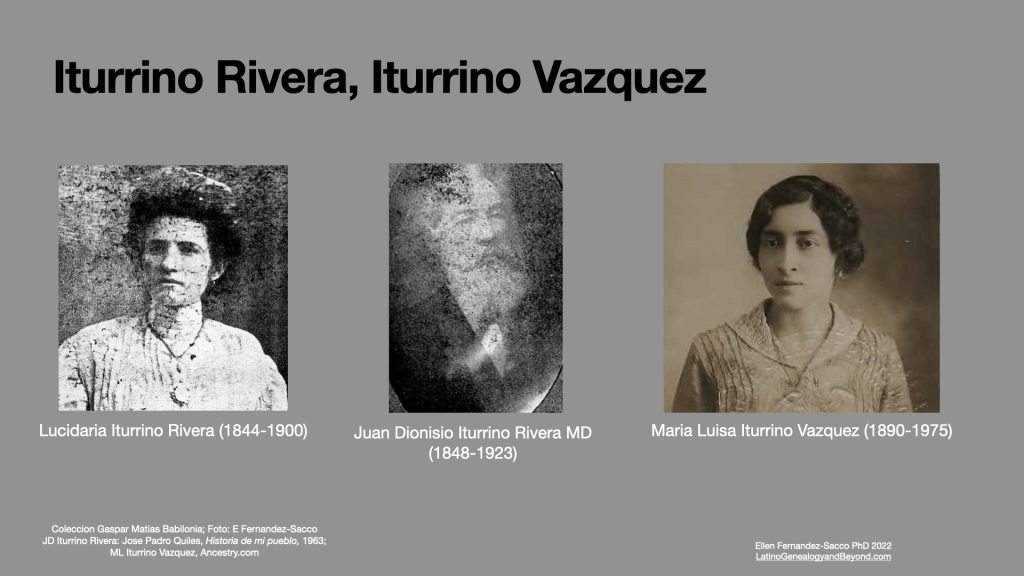

Felipe Iturrino married three times and had children from each marriage. His first marriage was to Teresa de Jesus Salome de Rivera Ortiz, daughter of Felipe Rivera and Juana Bautista Ortiz on 22 January 1844 in Anasco. With her, he had three children, Juan Dionisio, Lucidaria, and Eulogia Yturrino Rivera. [14] As adults, Juan Dionisio was a medical doctor, and Eulogia was a teacher appointed by Spain in Quebradillas.

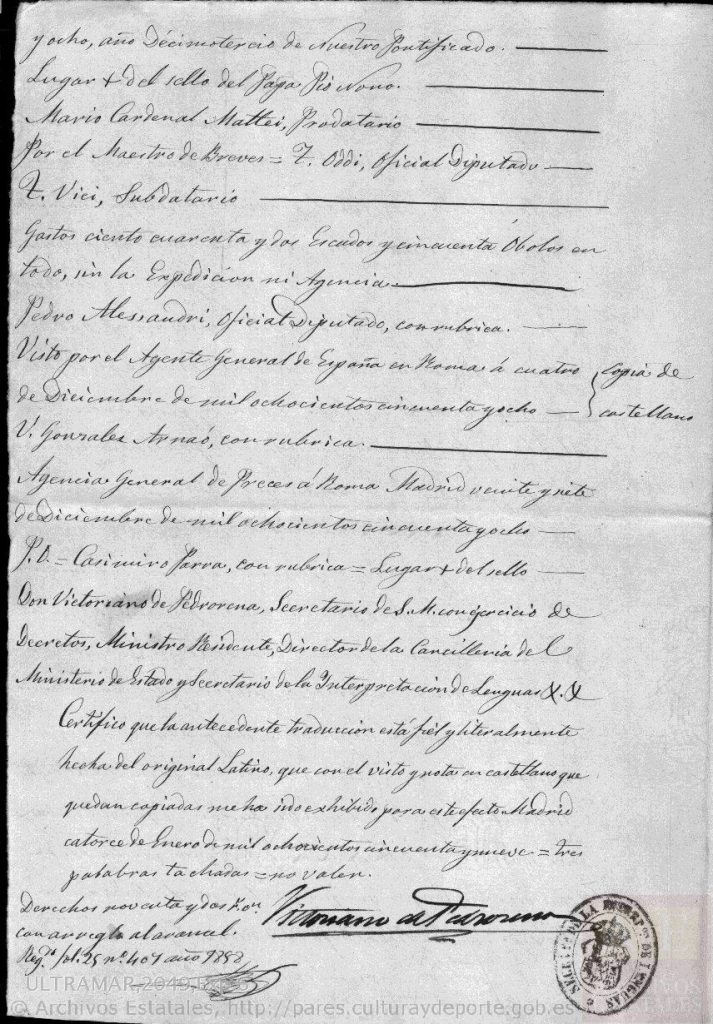

His second marriage was to Teresa’s sister, Maria Gregoria de Rivera Ortiz on 27 June 1859 in Anasco. On PARES, there are documents for an 1859 dispensation from Spain that was granted in order for the couple to marry despite the ‘primer grado de afinidad‘ (first degree of affinity) that indicates a sibling is involved. The process took about a year. [15]

What is remarkable is the number of people who had to sign off on the permission, with each stage likely having fees well beyond those for consanguinity on the island. Felipe and Maria Gregoria also had three children, Carmen, Adolfo Sinforiano and Julian Aristides Yturrino Rivera. His last marriage was also in Anasco.

On 12 May 1892 Felipe married for the third and last time, to Francisca Vazquez Ayala. [16] He had nine children with her: Carlota, Ysabel, Rogelio, Jose Roque, Jesus Maria, Elisa, Maria Carlota, Catalina and Mariana Yturrino Vazquez, born in Barrio Corcobada Rural, Anasco.

Lucidaria Iturrino Rivera married Adolfo Emeterio Babilonia Quinones (1841-1884) about 1868. An educator, agriculturalist, and musician, he was nominated to the post of Inspector General of Public Education for Puerto Rico by Governor La Torre in 1872, a post later given to a Peninsular with the political changes brought by Governor Primo de Rivera. Because of that he fled to the Dominican Republic for a short time and then returned to teaching in San Sebastian and Aguadilla. He died shortly after being notified by the new Governor Marquez de la Vega that he was given the post of Inspector General of Public Education in 1884. [17]

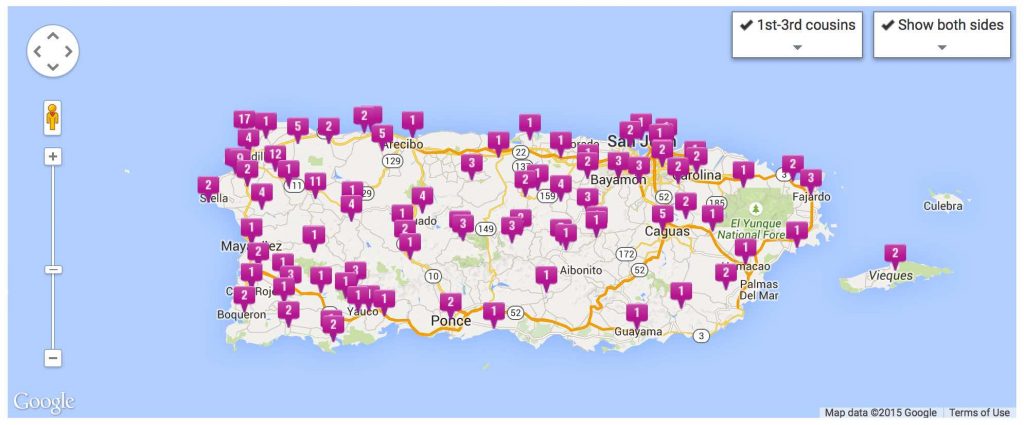

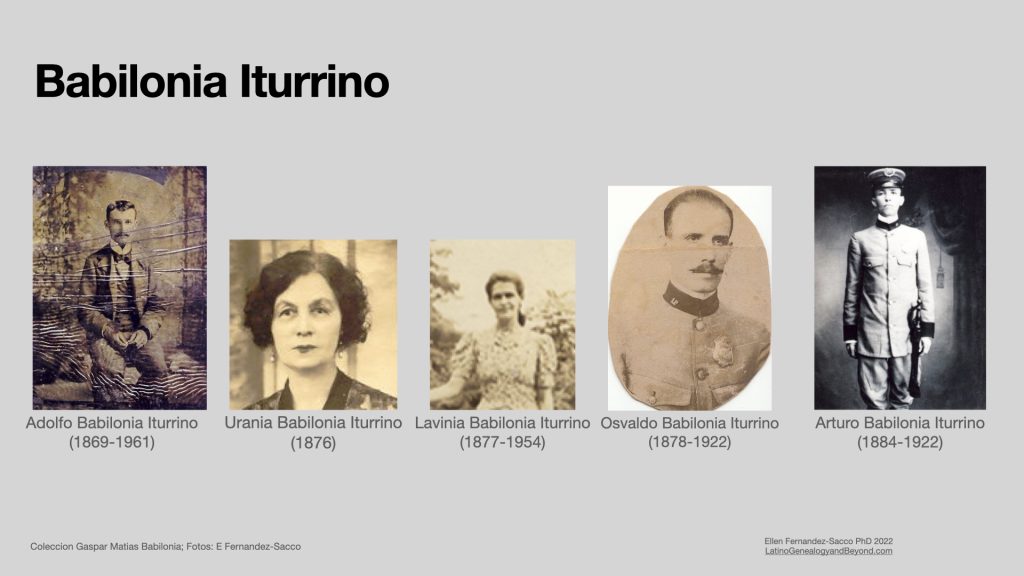

Adolfo Babilonia and Lucidaria Iturrino had 12 children: Adolfo Melquiades, Enriqueta, Olivia, Urania, Lavinia, Osvaldo, Alfonso, Amelia, Jorge, Viola, Arturo Carmelo and Simon Fidel Babilonia Iturrino. Here are photographs of five of them, taken in the early 20th century. They lived in Anasco, Moca, Isabela, San Sebastian, Arecibo and New York.

As a child, my mother remembered seeing Adolfo Melquiades Babilonia Iturrino astride a white horse, wearing a white linen suit and pith helmet as he went from location to location as Colector de Rentas Internas (Collector of Internal Revenue). Adolfo owned a coffee farm in barrio Cruz, Hacienda Laura, where his grandson, Gaspar Matias Babilonia spent part of his childhood. Osvaldo Babilonia Iturrino became Jefe del Policia Insular, Head of Insular Police; given his uniform, his brother Arturo also served in the Insular Police.

Threading these fragments of details back in time offers some sense of how one Basque emigre came to Puerto Rico, and left generations of descendants. Perhaps more details about them in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries will soon come to light. The larger context of this history still has much to provide about the connections to enslavement, politics and education of that era.

References

[1] Miren Egana Goya, Presencia de los pescadores vascos en Canada s. XVII. Testimonio de las obras de Samuel de Champlain (1603-1633).

[2] Brad Lowen, Intertwined Enigmas: Basques and St Lawrence Iroquoians in the Sixteenth Century. C3, 57-75.

[3] Brad Lowen,”Introduction to the Basque Papers.” Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 33:1, 2018, 1719-1726, 7-19, 7, 14.

[4] “Salt Cod, Chicken, Slavery and Yams.” 28 Nov 2014 https://elvalleinformation.wordpress.com/salt-cod-slavery/

[5] Manuel Valdes Pizzini, La imperiosa necesidad del bacalao: Puerto Rico y Terranova en la Ecología-Mundo. Relaciones Internacionales, No. 47, Jun-Sep 2021, 163- 179; 171.

[6] Birgit Sonneson, Vascos en la diaspora: La emigration de La Guaira a Puerto Rico, 1799-1830. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Sevilla, 2008.

[7] Acta defuncion, Rosalia Beles Camacho, 13 Nov 1804, San Jose de Mayaguez, Libro 2 Defunciones, Folio 136. Rosalía Vélez Camacho, administradora, viuda de Don Antonio Yturrini. Dejó por hijos a Juan, Bentura, José, Antonio, Candelaria y Benita. Oficios de entierro doble en tramo de 8 reales. Email, Iris Santiago, 17 Dec 2007.

[8] Acta nacimiento, Pedro Juan Yturrino Velez, 17 Jul 1780 [22 Jun 1780] San Jose de Mayaguez, Libro 3 Bautismos, Folio 22v. Email, Iris Santiago, 23 March 2008. “L3B F 22vuelto 17 jul 1780 Pedro Joseph, de 19 días, h.l. Don Antonio Iturrino y Da. Rosalía Vélez. Padrinos: Don Agustín Fernandino y Da. María Felicia de Mathos. “

[9] Benito Iturrino Velez + Ysidra Morales Crespo, 16 Jan 1814 Anasco. His daughter Eleuteria Iturrino Morales lived to age 103. She died in Barrio Zanja, Camuy in 1928.

[10] Acta defuncion, Felipe Yturrino Arzua, Registro Civil, Anasco, 17 Marzo 1894. F72-73 #75 Image # 7-8, Historical Records Collection, Puerto Rico, FamilySearch.org

[11] Carlos Encarnacion Navarro, AGPR, Fondo de Protocolos Notariales, Serie Aguadilla, Pueblo Aguadilla, Caja 1434, Escribanos otros funcionarios, 1852-1878, 10 Mar 1864 (Folio no numerado), p.67. The identity of Cristobal Soto in Barrio Plata, Moca remains to be established.

[12] Carlos Encarnacion Navarro, AGPR, Fondo de Protocolos Notariales, Serie Aguadilla, Pueblo Aguadilla, Caja 1434, Escribanos otros funcionarios, 1852-1878, 4 Ago 1864 (Folio no numerado), p. 71.

[13] “Anasco. Relaciones de las multas que ha impuesto varios Alcaldes en el mes de Noviembre proximo pasado por las causas que a continuacion se expresan.” Gazeta de Puerto-Rico. [volume] ([San Juan, P.R.), 11 Jan. 1842. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2013201074/1842-01-11/ed-1/seq-4/>

[14] Acta de matrimonio, Felipe Yturrino Crespo + Teresa de Jesus Salo Rivera, 22 Jan 1844, Libro 12, Folio 139, Anasco. Email, Wilfredo Quintana, 2008. His mother’s maternal surname appears instead of Arzua.

[15] Sobre dispensa matrimonial de Sr. Iturrino y Srta. Rivera. 1858-1859. PARES | Spanish Archives ES.28079. AHN/16//ULTRAMAR,2049,Exp.6, September 1858. PARES.mcu.org

[16] Acta de matrimonio, Felipe Yturrino Crespo + Maria Gregoria Rivera, Libro 12 Folio 217v, Anasco. Email, Wilfredo Quintana, 2008.

[17] Angel M. San Antonio, Hojas Historicas de Moca. Moca: Emprearte EB, 2004, 160-161.