While in Puerto Rico over a decade ago, I bought copies of old photographs at Tienda Cesto in Aguadilla. Part of the store was given over to tables with sets of binders, each containing photographs from different municipalities. There were a small number of images of Moca that I bought. Looking for items for the next Black ProGen Live (Ep.72 – join us!), I pulled my small binder of photographs as I remembered an image with a coffin. As I’d soon learn, my connections were closer than I could’ve imagined.

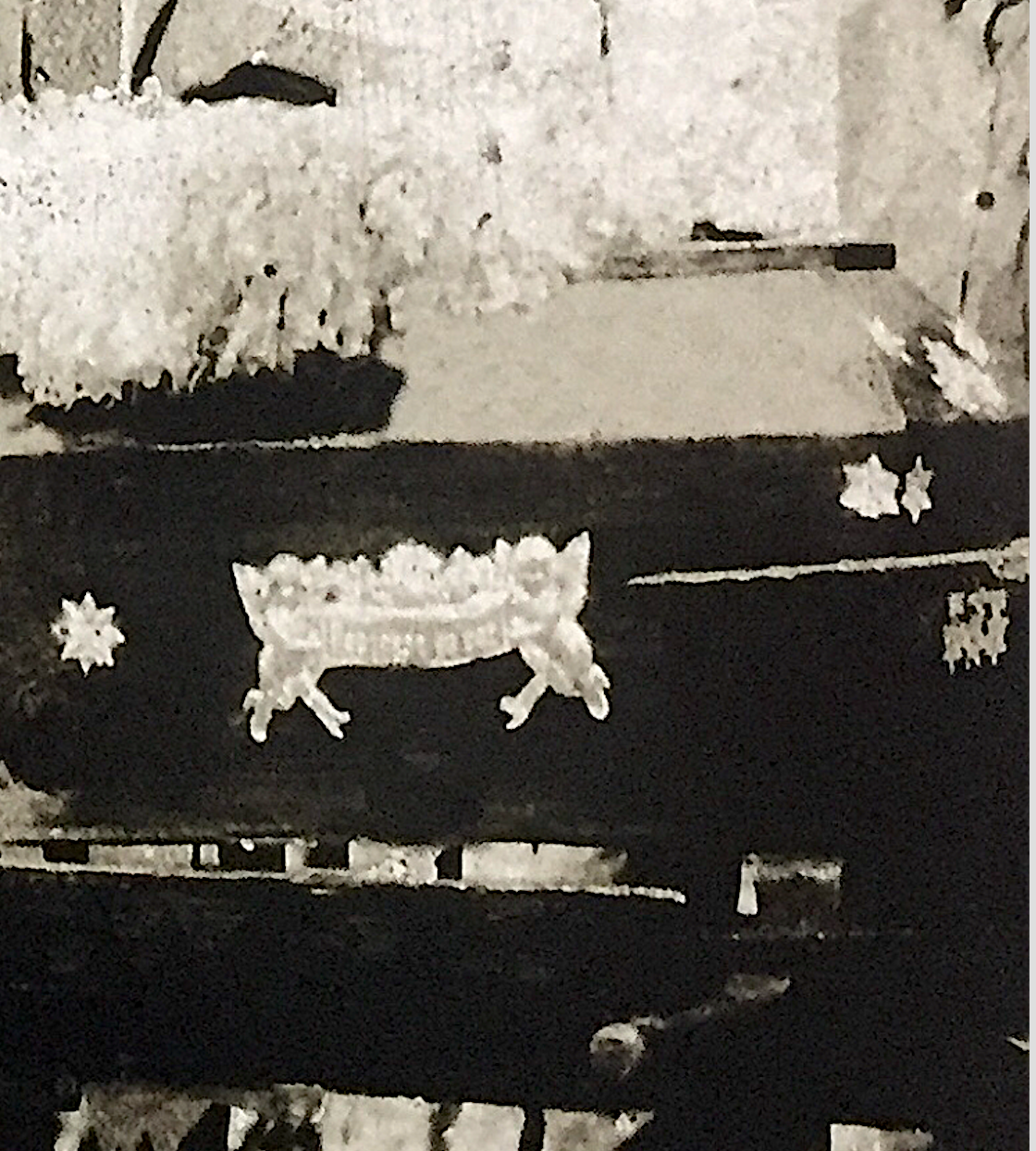

Near the end of September 1929, a group of men and children stood in the midday sun before a coffin for a photographer, in Moca. According to the notation on the photograph, it was Balbino Gonzalez’ father and the location was in Barrio Plata, a rural location some 5 miles away from the center of town.. Recently finished, the shiny coffin, painted a dark enamel color and embellished with stamped metal decorations sat on a frame that was to shortly transport Gonzalez to his final resting place in the Viejo Cementerio Municipal de Moca in what was popularly known as Calle Salsipuedes . Given that the son’s name appeared with a date, I used that as a guideline to find Balbino Gonzalez’s father in the Registro Civil. The death actually occurred ten days later.

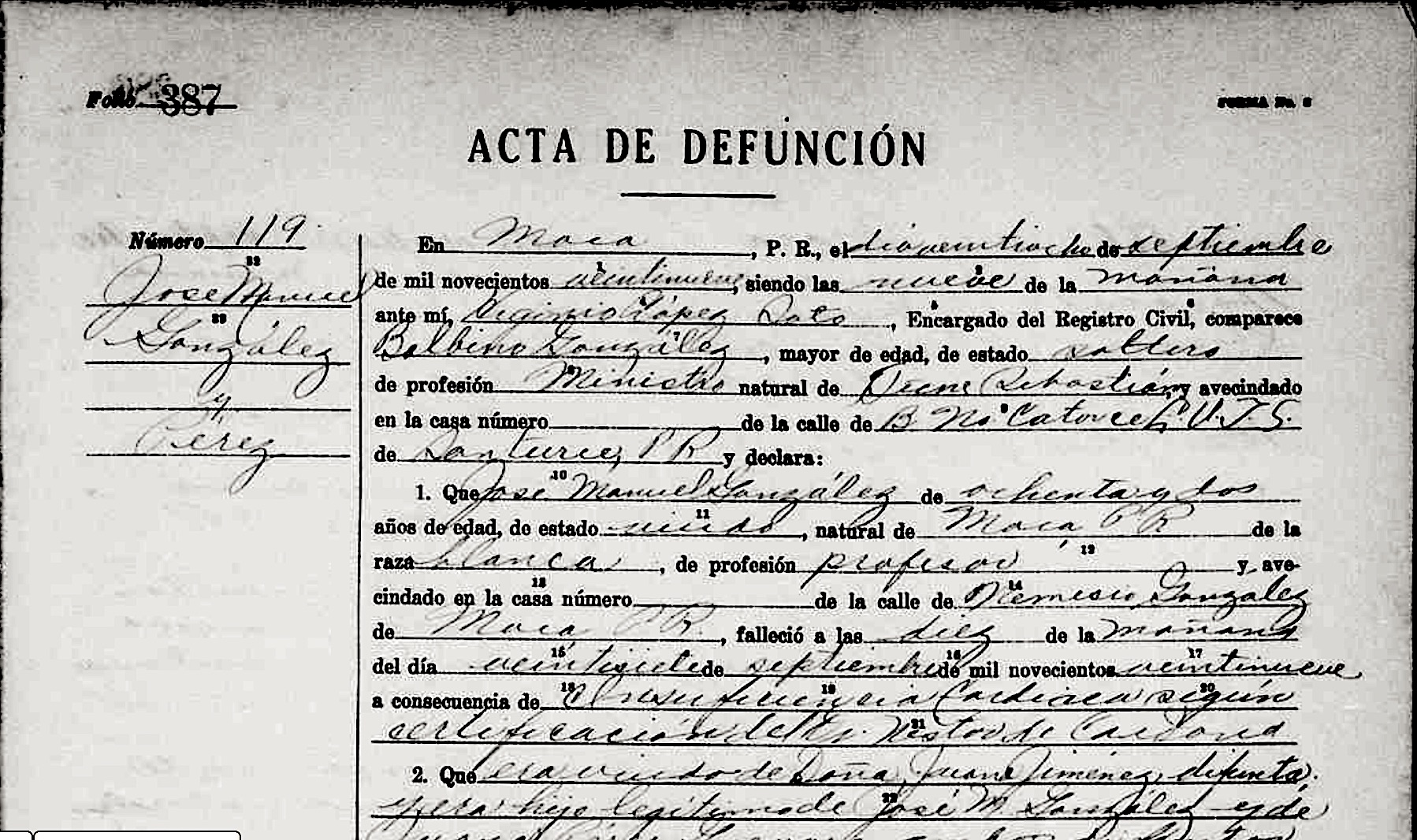

Acta de defuncion: 29 September 1929

Balbino Gonzalez Jimenez was one of five children of Jose Manuel Gonzalez Perez (1863-1929) and Juana Bautista Jimenez Soto (1868-1926). He is the young man in the suit at the center of the photograph. He was single at the time of his father’s death on 27 September 1929. He came from Santurce where he was a teacher, to report his father’s death to the Registro Demográfico. His suit, tie and hair speak to fashion in the metropolis of the San Juan metropolitan area, a self awareness already honed by his profession. The other men in the photo wear looser fitting shirts, and the straw boatera hat is a respectful nod to artesanos and locals that decades later became part of the dress of Los Enchaquetaos, a fraternal group founded by Pedro Mendez Valentin. Here the stiff hat functions much like the formal top hats used by funeral staff.

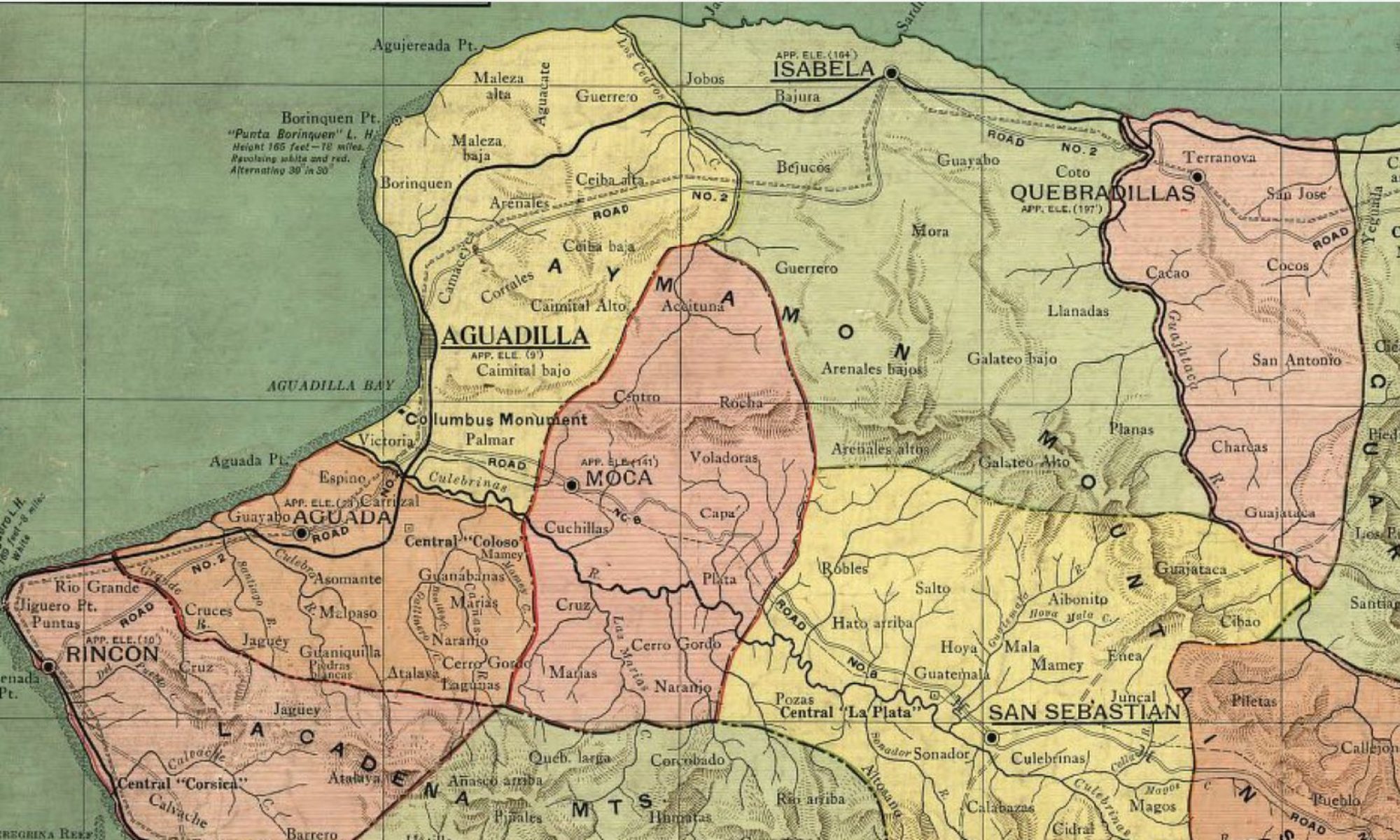

Jose Manuel Gonzalez Perez, was an 82 year old widower, who worked as a professor. He lived on Calle Nemesio Gonzalez, and died the morning of 27 September 1929 of cardiac insufficiency. It’s likely that as his condition worsened, family was contacted as his time neared. His son Balbino Gonzalez Jimenez was summoned home, and he was the informant for his father’s death record above. While he was unable to report the names of his father’s paternal and maternal grandparents, he gave the names of Jose Manuel’s parents: Jose M. Gonzalez (ca 1814-bef 1899) and Juana Perez Guevara (1819-1899) [1] Jose Manuel was one of three siblings from Barrio Plata, a long narrow municipality that borders San Sebastián on its eastern border.[2]

La ultima parada: from workshop to cemetery

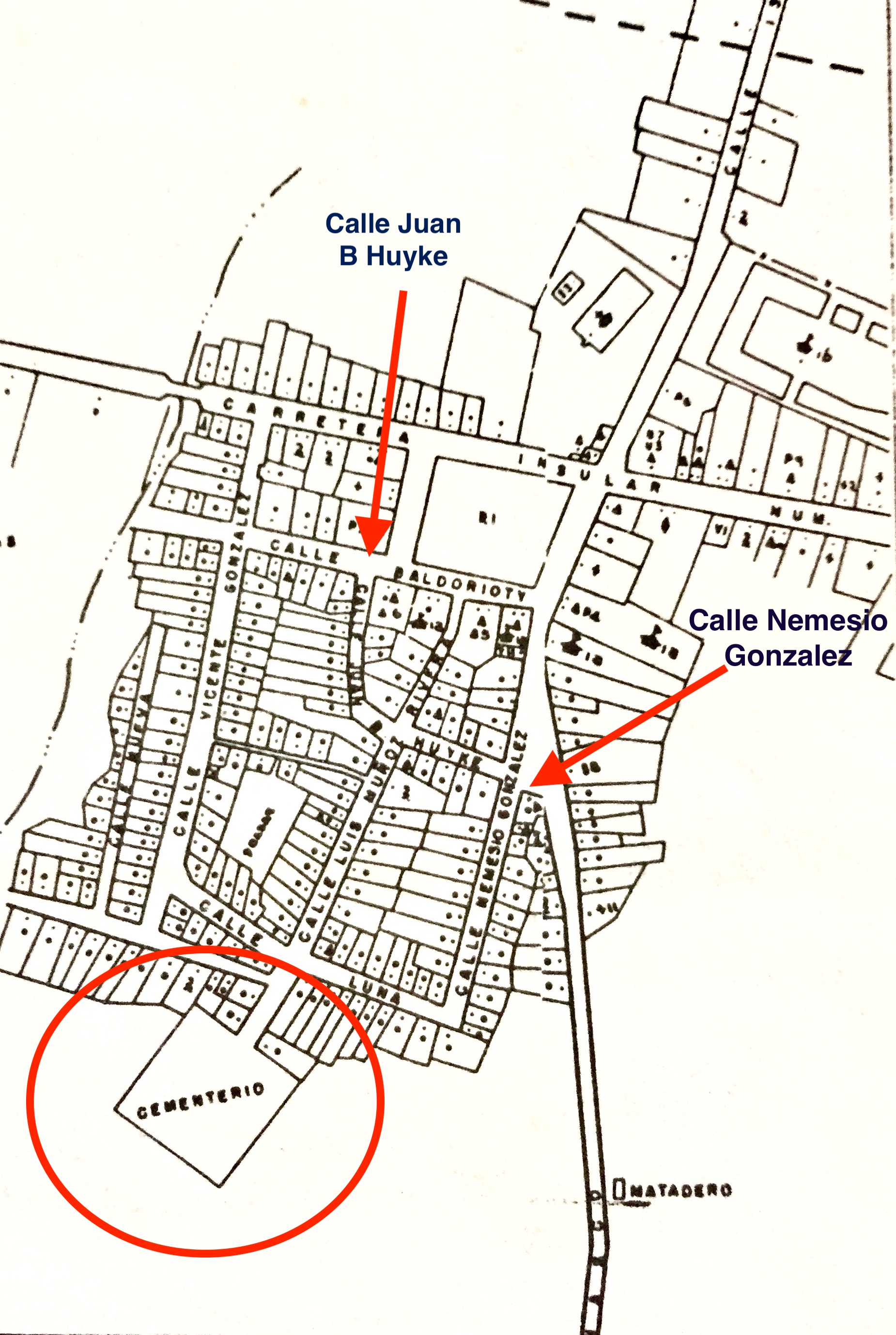

A 1947 map of Moca shows the former location of the cemetery at the end of the street that leads from the Plaza in front of the church to the Cementerio Municipal.

Among the group standing in the photograph on the right, is a tall pale man, who may in fact be Alicides Babilonia Talavera, my great grandfather. Later, his son, Alcides Babilonia López also made coffins in a nearby workshop.

Calle Nemesio González in Moca ran through Barrio Pueblo, and this is the street that Jose Manuel Gonzalez Perez lived on; my great-grandfather Alcides Babilonia Talavera and grandfather Alcides ‘Alcidito’ Babilonia Lopez lived in homes next door to each other on Calle Juan B. Huyke. This is the backdrop of the 1929 photograph. As this was before the establishment of a funeral home, many people had a wake at home, and the Gonzalez family probably did the same. Given the heat, it lasted a day, with ice piled beneath the coffin and a plate piled with salt placed on the chest of the deceased. The lid may or may not have a glass window, so that the case can stay closed and the deceased could still be seen.

The man on the far right

Among the group standing in the photograph there on the right, is a tall pale man, who may in fact be Alicides Babilonia Talavera, my great grandfather. Later, his son, Alcides Babilonia López also made coffins in a nearby workshop.

According to my cousin Diany, Alcides was known for his coffins. When he was younger, he had a room with samples where people could choose fabrics for the inside of their coffins. There were always stories with a touch of the supernatural about them. He had an order from a man who needed a coffin, and worked on making it with a hammer. after midnight, he couldn’t find the coffin. Another coffin was tossed through the window, so he picked it up and finished the job.

Finish & detail: 1929

The details in the photo give an idea of decorative funerary practices in rural areas, which ran from the simplest unadorned box to a highly finished coffin with stamped metal cherubs holding a garland inscribed with ‘Que en paz descanse’. Clearly then, this was top of the line and the maker stands at the head, arms folded behind him, separating him from the family next to him.

Center Left: identifying Lorenzo Caban Lopez, Sepulturero de Moca

Screenshot: EFS

The identity of the man in the flat top hat is Lorenzo Caban Lopez, who was married to Lucia Alonso Font (1874-1956). [3] In 1901 he was appointed by the municipal government as a Sepulturero y conservador (Gravedigger and caretaker) and as a Celador (Maker of grave markers and crypts) for the old Cementerio Municipal, which he did for 23 years until August 1936.[4] after his death, his son Feliciano ‘Chano’ Caban, who stands to the left, became Sepulturero. [5] He and his family lived on the edge of Barrio Pueblo, on Calle de la habana. As it happens, I share many connections with this Caban line.

Lorenzo was the father of Domitila Caban Lopez (1902-1982), my grandfather’s last partner before his death in 1948. She was a tejedora, a lacemaker and I exhibited some of her lace work at UPR Mayaguez along with that by other tejedoras, some who are no longer with us. Like lace, weaving these details together give us a recognizable pattern as we work through the questions.

By the 1940s

In the 1940 census, Alcides Babilonia Talavera was a divorced widower, and it is not until then that his occupation is listed as a maker of coffins. in the 1910-1930 census his occupation is Agricultor- finca de cafe (Farmer- coffee farm). By 1920, his ex-wife, Concepcion Lopez Ramirez (1863-1925) lived next door to him and had a business as a ‘modista’ a dressmaker, living with several of her children while Alicides lived next door with children as well. In January 1925, Concepcion died suddenly. His reaction was to call a photographer for one last image, altered to evoke the life of a portrait. It merely succeeded at lending an uncanny gaze emanating from her painted in eyes. I am not sure how much this experience shaped his funeral avocation, but he was likely well acquainted with the steps of caring for the dead, as people still arrived and departed from their homes.

My grandfather, also named Alcides, made coffins, and in 1940 appears as a “ carpintero – propio taller” a carpenter with his own workshop. It was the year he married my grandmother Felicita, who later died that year of tuberculosis, which took many family members. By 1948, knowing he was going to die, he made a simple pine box for himself, but that’s another story. He worked making coffins with his friend Rito Vargas, husband of Maria Lassalle, the lacemaker of Moca. Out of death comes a refashioning of self, family and the ways we decide (and are able to) to honor their lives.

Unexpectedly, a photograph brings me closer to the past and to even more relatives, as I learn more about the work of Lorenzo Caban Lopez and Alcides Babilonia Talavera. QEPD.

References

[1]Acta Defunción, “Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2001,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJD-J3PV : 17 July 2017), Jose Manuel Gonzalez Y Pérez, 26 Sep 1929; citing Moca, Puerto Rico, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico (city offices, Puerto Rico).

[2] Acta Defunción, “Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2001,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJD-FTL3 : 17 July 2017), Juana Perez Guebara, 17 Oct 1899; citing Moca, Puerto Rico, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico (city offices, Puerto Rico).

[3] Lorenzo Caban Lopez’ death certificate lists his occupation: Celador- cementerio, Gob Municipal hasta Ago 1936, 23 anos; Acta Defunción “Puerto Rico, Registro Civil, 1805-2001,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJD-NJMT : 17 July 2017), Lorenzo Caban Lopez, 14 Nov 1936; citing Moca, Puerto Rico, oficinas del ciudad, Puerto Rico (city offices, Puerto Rico).

[4] Antonio Nieves Mendez, Historia de un pueblo: Moca . Lulu.com 2008, 49.

[5] Victor Gonzalez, “Los Cuentos de Chano Caban” Mi niñez Mocana y algo más…. Segundo edición, Impresos Ideales, 1990, 19-21.

Discover more from Latino Genealogy & Beyond

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What great information from one photo. You are a great detective. Thanks for sharing.

Cariños, Evelyn

Mil gracias Evelyn! Thanks for reading!

I love your story, thank you so much for sharing. I found it very interesting. Ruth

That photo and the history behind it….priceless! Wow

Maybe you can help me, My father was Angel Sosa-Medina,from Aguadilla. My mother was Pura Nunez- Velazquez from Moca. I am trying to find were my mother was buired in Moca. July 1st through 7th I visited with my couisens i visited Aguadilla and Moca. I found my father grave, but in Moca, i could not find my mother. I was adopted by a family, who was station at Ramey A.F B. I did my Anserty DNA. My mother was born 1924 Died Aug 31st 1954 of TB My father was Born 1916 and died May 2, 2007. I was born May 19 1954. My father gave me up because he could take of me. My name was Ana Louisa Sosa.

Mona, I didn’t post your comment to avoid issues around identity theft. If you have a death certificate, that will say where your mother was buried. Look on FamilySearch.org (free, just have to register for account) and I think you should be able to pull it up. Let me know.

Ellen

Were you able to possibly locate his WW1/2 draft record if he registered to confirm if he was Alto, that would be just another confirmation. Great article and amazing chance in life that you were able to find that photograph. Thank you for sharing this, great blog.

Thanks so much Orlando. He didn’t register for either WW1 or WW2 draft.

Thanks so much for your kind words. I somehow missed the followup comment! Unfortunately Alcides Babilonia Talavera did not register for the draft. My grandfather did however. Remember the height is also relative as the other men in the photo are quite short.Death records do not record this information either… Oral history mentions height, nothing extreme, but he could be 5′ 10″ for example and still be taller than the others in the photograph.Granted this is a next generation, but Victor Gonzalez, author of Mi Ninez Mocana y algo mas…(1st and 2nd editions; Impresos Ideales, 1990) mentions that because of the rationing during WW2 that many men were shorter than they could have been. The post-war generation that lived in the US did indeed tend to be taller than this born in Moca during the 1940s. Apparently this could also be the case for WW1 and the period around the Spanish American War.

I may be related to Domitila, if this is the right family.

Thanks so much for reading! And yes, they are related to Domitila.