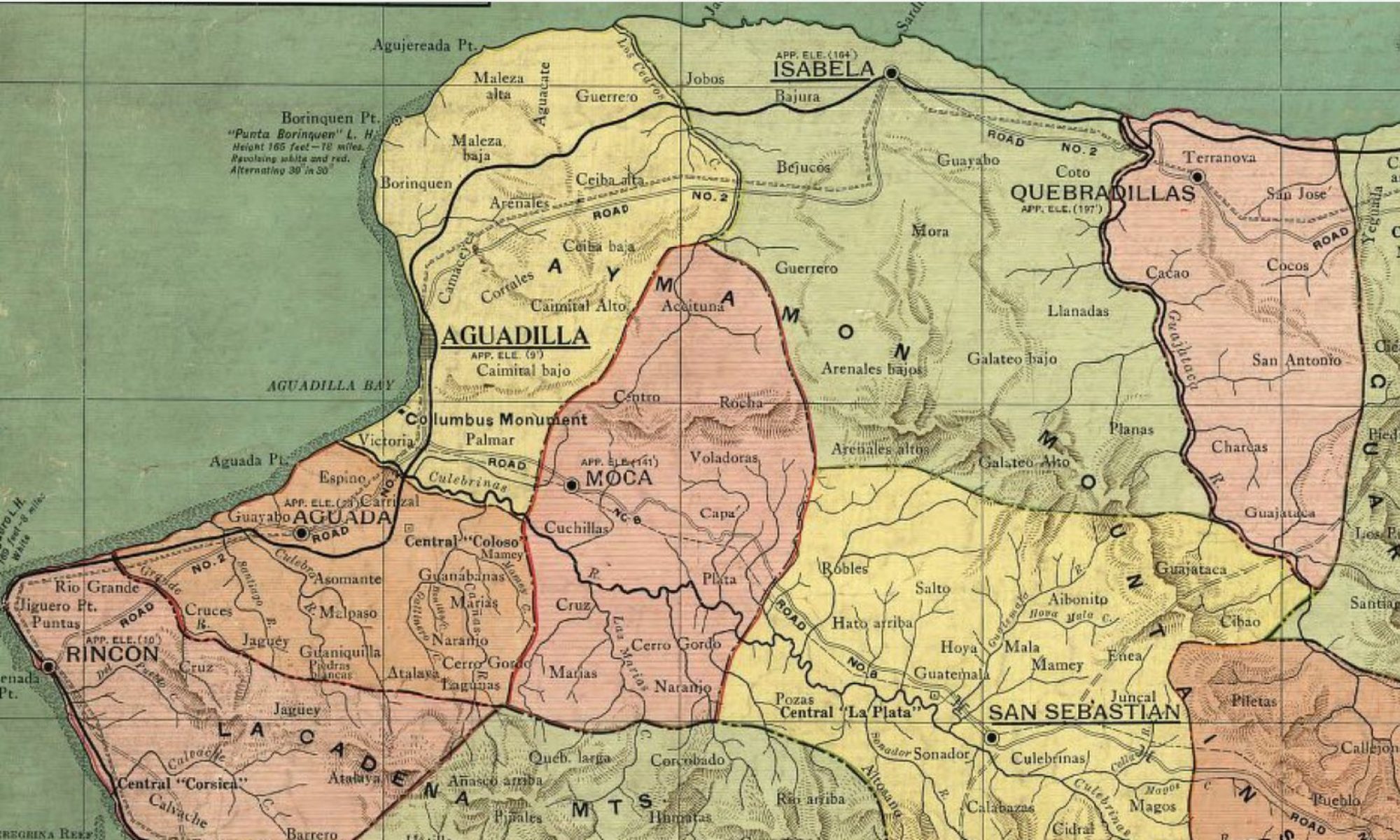

I’ve finally submitted the materials, tables and text to accompany Part 3 of the Missing Registro Central de Esclavo volume for Northwest Puerto Rico to Hereditas. This set of transcriptions of cedulas are from Caja 2 (item 2) of 1870. The essay focuses on facets of the lives of 55 enslaved people held by Cristobal Benejam Suria or Serra in 1870, a Menorcan who arrived in Puerto Rico about 1817. Other family members were also enslavers. Several Benejam family clusters are traced from the cedula through the Registro Civil and census records, to reconstruct some of their history.

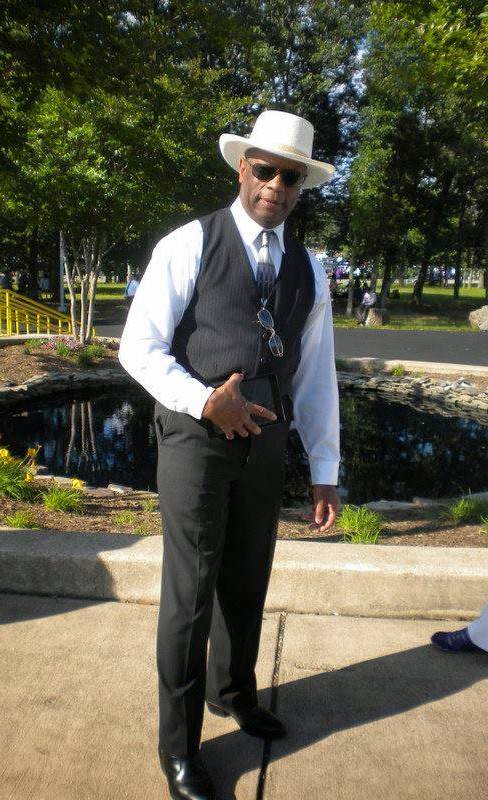

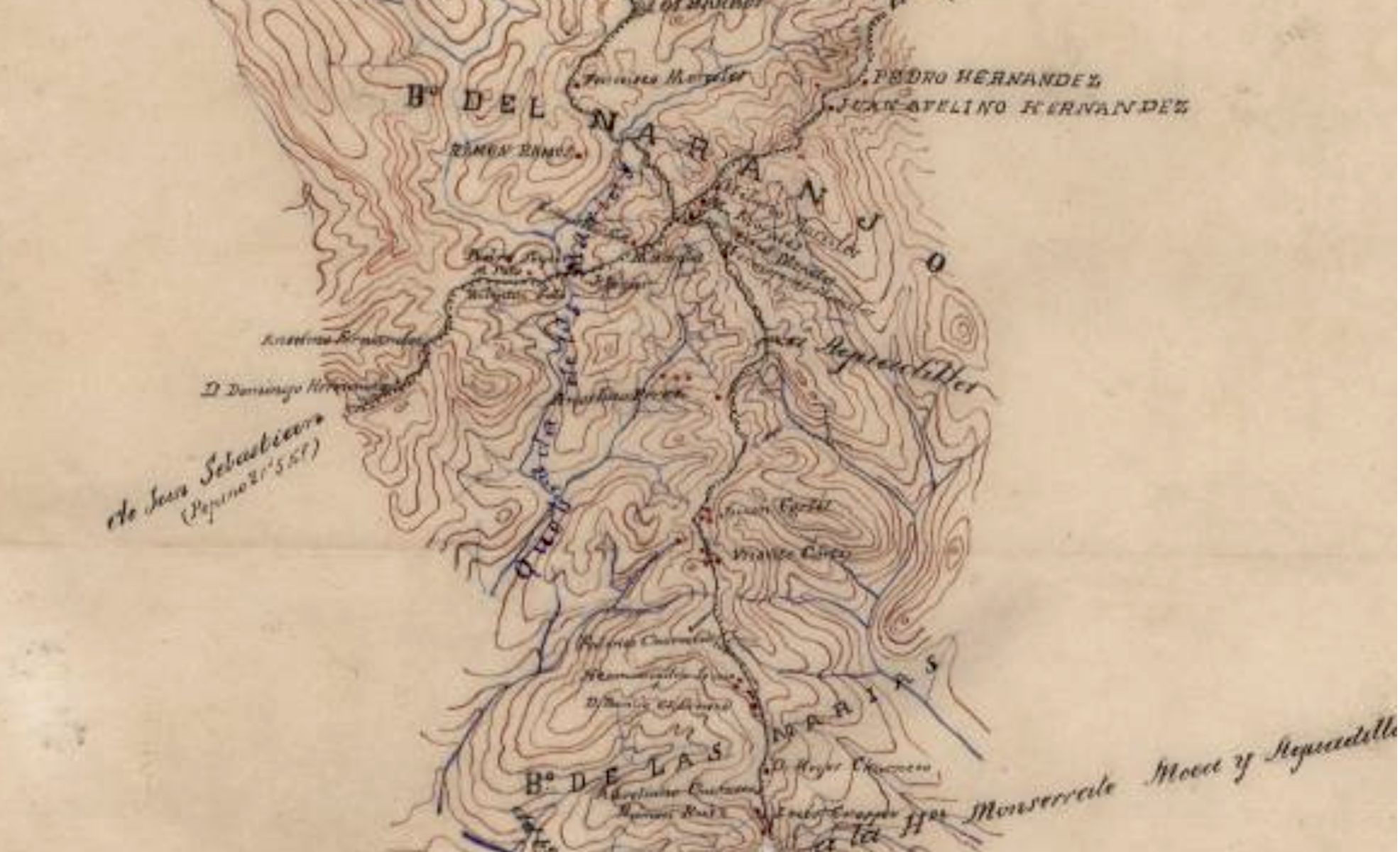

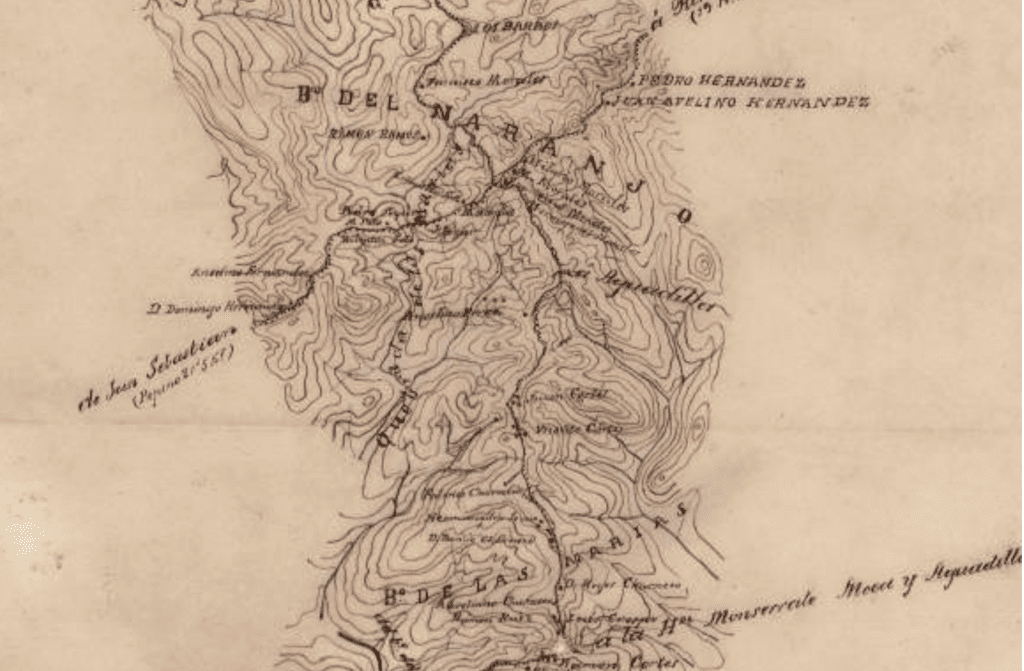

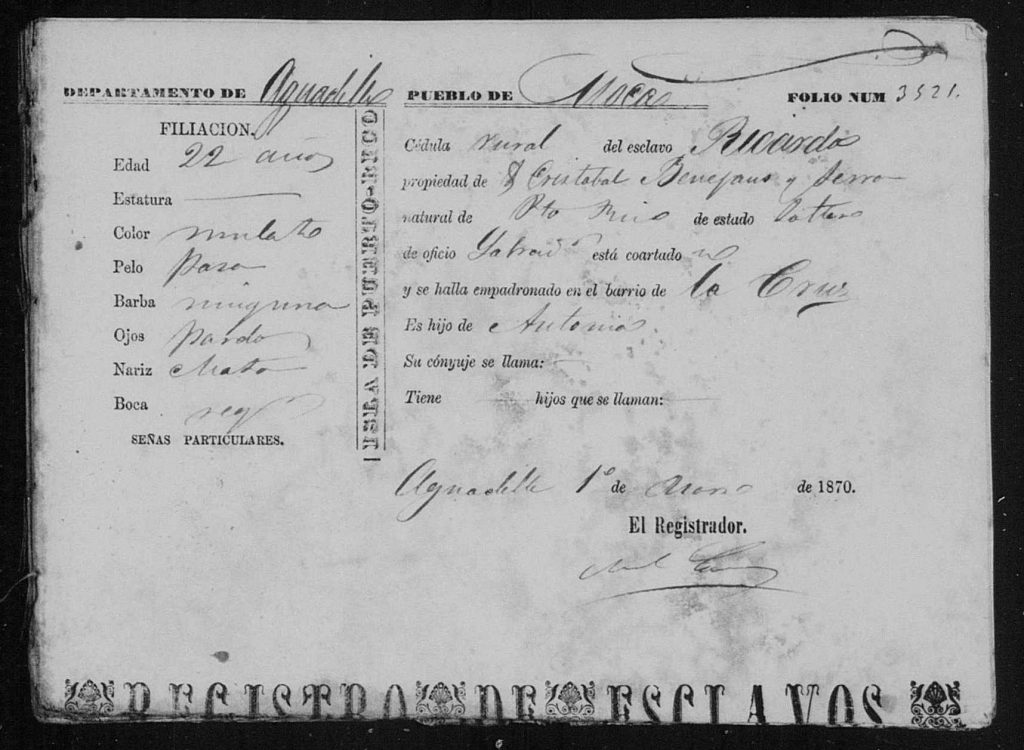

As it turns out, when I mentioned my project to my cousin, Julio Enrique Rivera, he mentioned that his dad, Julio Ester Rivera (looking very dapper in the photo above) was a Benejan. His great grandfather was Ricardo Benejam Vargas (1848-1924) born into slavery, the child of Maria Antonia Vargas and Pedro Benejam. This is Ricardo’s cedula of 1870.

I am struck by how fragmented some of the resources available are.

Some of the documents i’m looking at:

Parish records

Municipal Document series – Censo y riqueza de Moca 1850

Cedulas, Registro Central de Esclavos

Registro Civil

What I wish there were more of for NWPR: census, contracts, notary documents; basically a database that can help descendants pull these fragments together.

As for books & articles, am rereading Benjamin Nistal-Moret’s “The Social Structure of Slavery in Puerto Rico” (1985). I’d like to use the tables as a model for what I am working on, which is information missing from the numbers he is using. This was “the first time in Puerto Rican historiography, an analysis of this magnitude has been completed with a computer.” He tells an interesting story about locating a missing 1872 Registro Central de Esclavos volume at the Library of Congress, microfilming it and returning it during the summer of 1975. As he did his work in the 1980s, his statistical work was entered onto punch cards of a computer program used in sociology. Which volume it was, Nistal-Moret doesn’t say.

I wonder how much archival material was lost, for instance, after the US returned the series of documents of the Gobernadores Espanoles – T1121 Record Group 186- Records of the Spanish Governors of Puerto Rico (impounded on the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1898) were transferred to the National Archives in 1943 and returned to Puerto Rico by joint resolution in 1957. The microfilm of the Registro de Esclavos and the Registro Central de Esclavos are part of that huge series, and NARA has a free version at the link above.

What I try to do in this series of articles are mini-histories of persons that appear on the 6 x8″ cedulas. Connecting someone in 1870 to their appearance in the Registro Civil that begins in 1885. The process takes time, as there is no mention of enslavement, save in the surname ‘Liberto.’ Some take different surnames, while many kept their enslaver’s name, or took that of a different owner when sold before 1870.

Some of the descendants of Luisa Benejan born about 1819 appear among the cedulas of Caja 4 of the Registro de Esclavos, while three appear in the Registro Civil. She doesn’t turn up on the Registro Civil. Still, the documents together reconstruct her family.

Also reconstructed are early family trees for Pedro Benejam of Moca, born about 1817 in Moca, and who partnered with Maria Antonia Vargas, who lived until 1902 and lived in Bo. Pueblo, Moca. Among their descendants is where my cousin Julio Enrique Rivera’s line connects. The families created after emancipation were often female headed households, with daughters that worked in the local service economy, and sons in agricultural labor.

We must continue to say their names.

References

Ricardo, 22, 3531. Caja 4, Registro de Esclavos, 1867-1876. “Puerto Rico Slave Registers, 1863-1879”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSK3-Z3WY-S?cc=3755445 : 21 October 2021), > image 1 of 1.

Benjamin Nistal Moret, “Problems in the Social Structure of Slavery in Puerto Rico During the Process of Abolition, 1872”. Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Frank Moya Pons & Stanley L. Engerman, eds.Between Slavery and Free Labor: The Spanish Speaking Caribbean in the Nineteenth Century, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1985, 141- 57.