Cartas de emancipación: Letters of Freedom

As three historians of Cuban slavery recently wrote,”Los notarios eran parte de este sistema de “escribir la esclavitud.” — Notaries were part of this system of “writing enslavement”, literally creating the legal structures through documents that recorded and controlled the lives and movements of over 51,000 enslaved POC by 1846. In this way, the documents further defined citizenship within a slave holding society.[1] What I thread together here is the history of several people held in bondage, the predicament of pursuing freedom, its purchase and my own project of transcribing parts of a missing volume these certificates were entered into. At the end of this article is a translated list of names of those enslaved ancestors who gained freedom from one transcribed box of notarial documents.

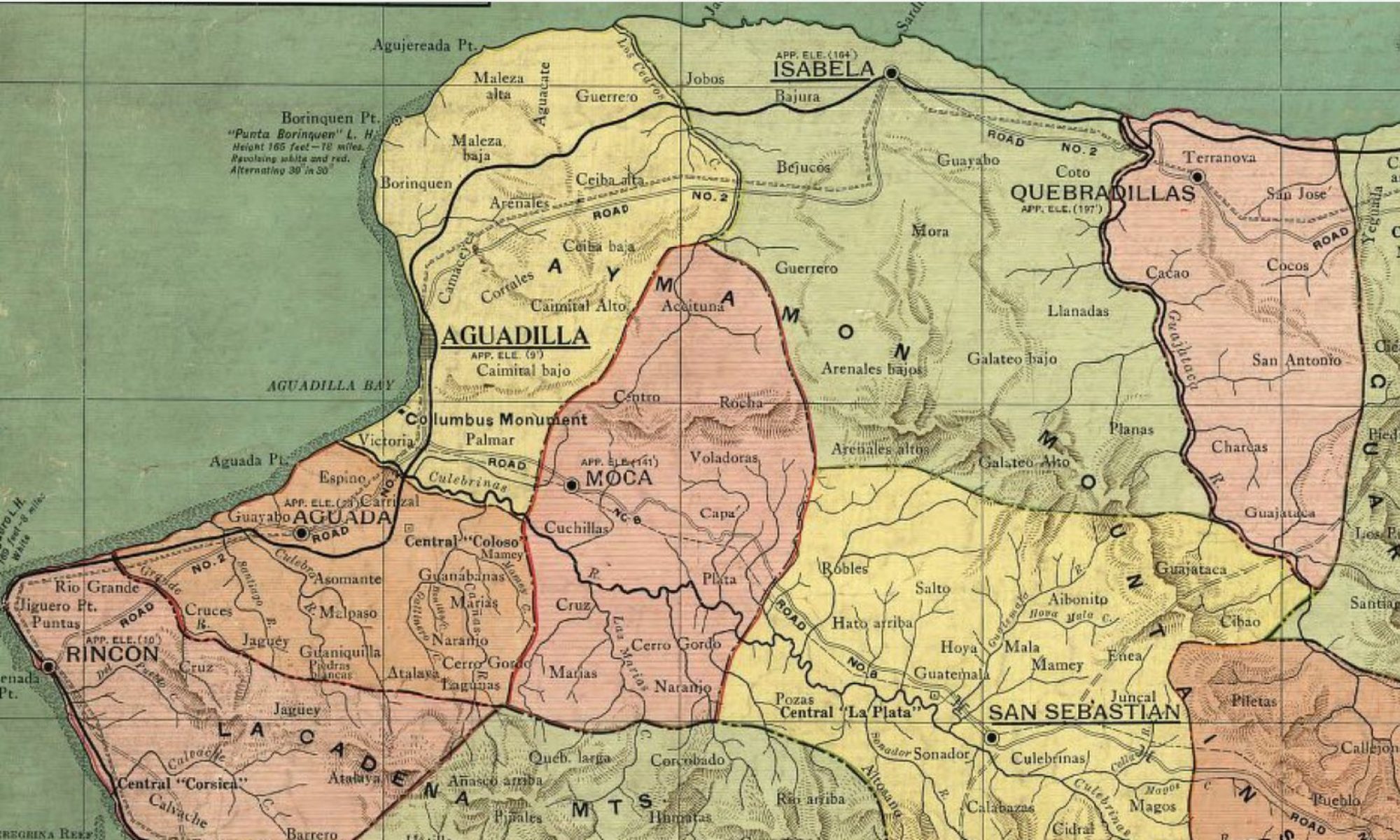

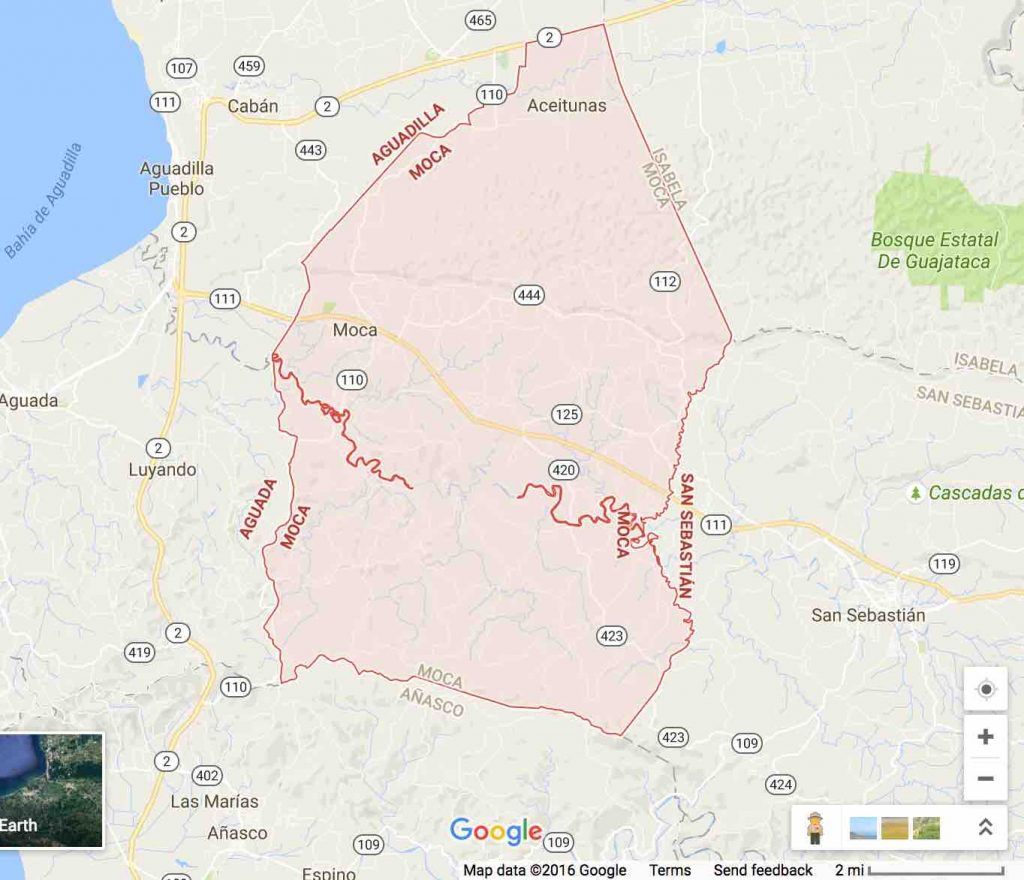

The run of notarial documents in Caja 1444 show that between January 1848 and the end of January 1852, the elites of Moca freed, sold and bought enslaved people.[2] Some distinctions made between those who were servants versus those who were laborers, but when a Carta de emancipación (Letter of Freedom) was issued, the bearer had proof of freedom that hopefully, led to self determination.

Several things become clear in this particular collection of notary documents, only 19 slaveholders liberated their human property, while 61 slave holding inhabitants continued to participate in selling them. Despite any bonds of blood or call to family that might exist, the exchange of money was paramount. The odds of gaining freedom in mid-nineteenth century Puerto Rico were indeed challenging.

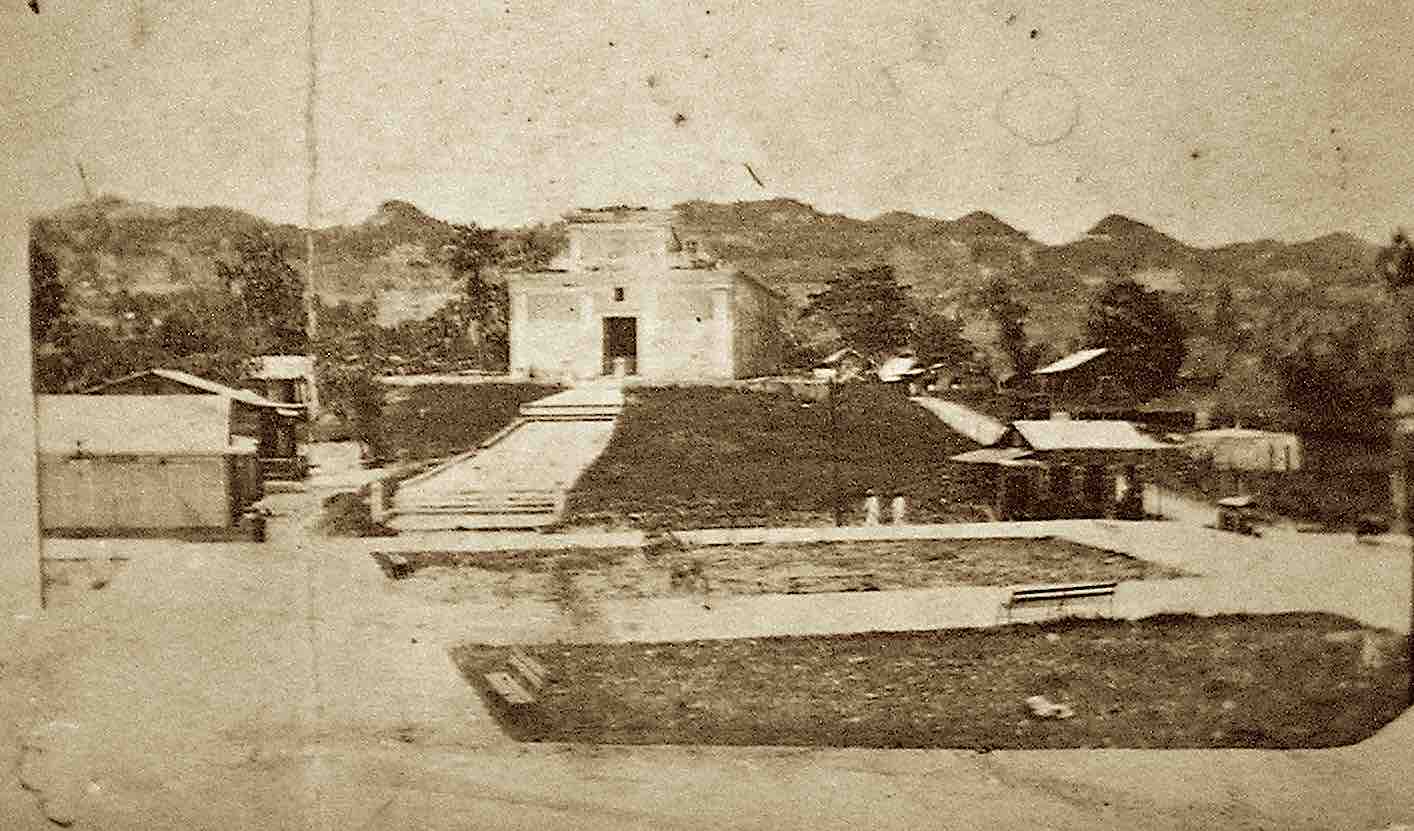

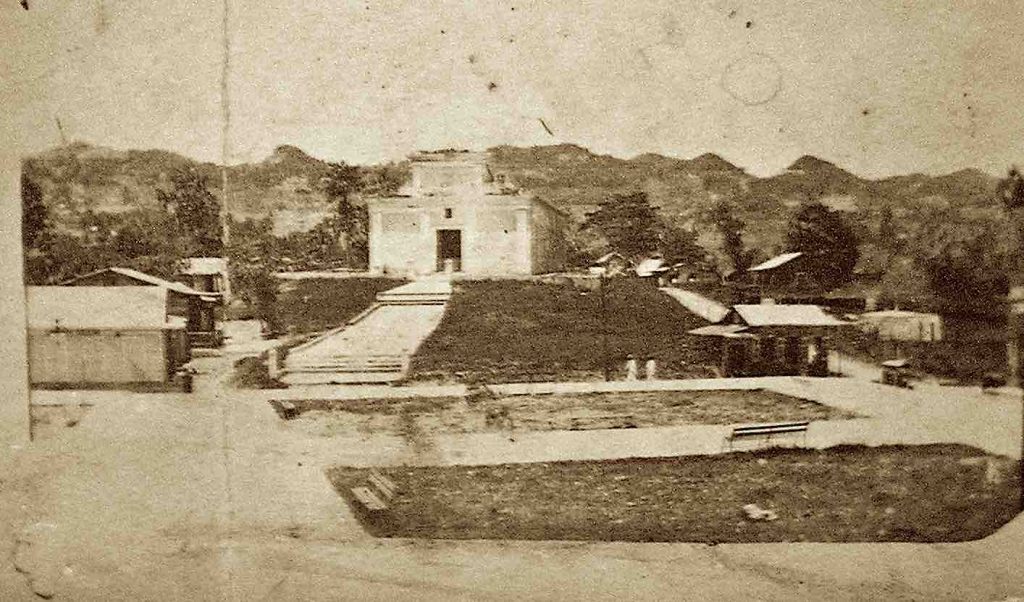

The plaza at the center of Barrio Pueblo was used for drying coffee, and this 1914 image is telling of Moca’s deeply agricultural context. This town center was the neighborhood where many who gained their freedom moved to in search of employment. At this time, just 41 years after the end of slavery in Puerto Rico in 1871, a significant number of people from elders to adults had some experience with enslavement. I met their descendants in 2000s, and if we speak of context, there is not a single family member untouched by slavery.

Those Who Were Freed

Eight of those freed were male and eleven were female, the youngest being Ramona, 7 months old, and the oldest, Marcos, 70, born in Santo Domingo about 1781. He may have witnessed the events of the Haitian Revolution prior to reaching Puerto Rico; Ramona, if she survived, may have witnessed the string of uprisings that went across Northwest Puerto Rico with the Grito de Lares in 1868, and perhaps actively participated in the struggle for equality that continued for decades.

Some may still carry their memories, so there may be oral histories that tell of their lives. At the very least, their traces in the historical record speak to the constraints they had to live under, and hope for a better life after emancipation despite a spectrum of challenges.

The Emancipation of Mauricio and Ramona

Among those who gained their freedom were children, among them Mauricio 1 1/2 whose mother Monserrate paid for his letter of emancipation; 7 month old Ramona was purchased by Maria Encarnacion from d. Alberto Soto. In 1848, Maria Candelaria paid her slaveowner d. Cristobal Benejan for her own freedom, and in 1850, was able to buy that of her two-year-old daughter Maria, who was born on Benejan’s property and was raised by Paula, another enslaved woman who worked there. As of 1849, “…colonial authorities permitted interested parties to purchase the freedom of infant slaves at the time of baptism, for the sum of twenty-five pesos. The infant however, remained with the master who owned his/her mother until he/she reached adulthood.” [3] So far, there is no indication that freedom was Benejan’s intention.

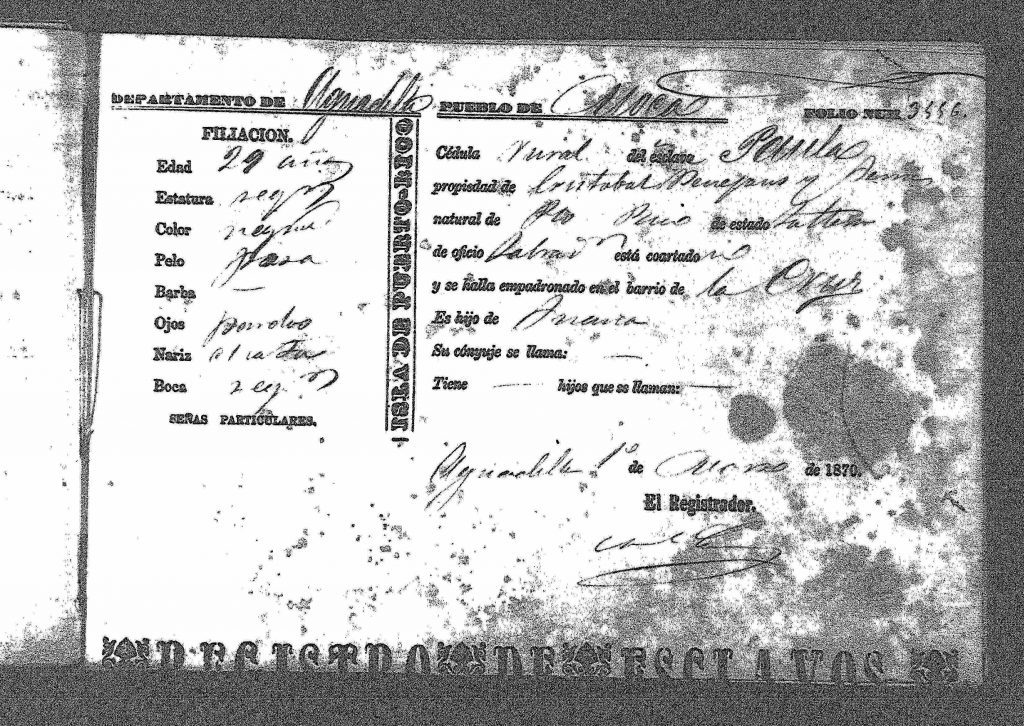

In a transcription project on the 1870 Registro de Esclavos I’m working on, Cristobal Benejan y Suria was among the largest slave holders in Moca, with 54 persons. At this point in 1870, another three years of labor was required prior to emancipation.

Note this was 36 months of uncompensated labor, caught up in expectations of gratitude toward former owners on the part of the freed. Historian lleana Rodriguez-Silva wrote that “Political practices such as gratitude highlight the liberal features of benevolence and paternalism and undermine efforts to critique the structures of power, especially through critiques of racialized domination.” [4] So, the histories of abolition in the Caribbean were revised and rewritten to celebrate rather than expose how power functioned in the lives of POC.

Among the certificates of those owned by Benejan in the Registro, Paula’s name appears as the mother of Loreto, 11 (b.1859), and Calista, 1 (b.1869). There is a certificate for Paula, 29 (b. 1849) daughter of Juana, born the same year Maria Candelaria gained her freedom. What happened to the Paula that cared for Maria Candelaria’s daughter Maria? Was Paula freed in the two decades after she was entrusted with the care of Maria? Did she pass away before 1870? I’m left with more questions than I can answer.

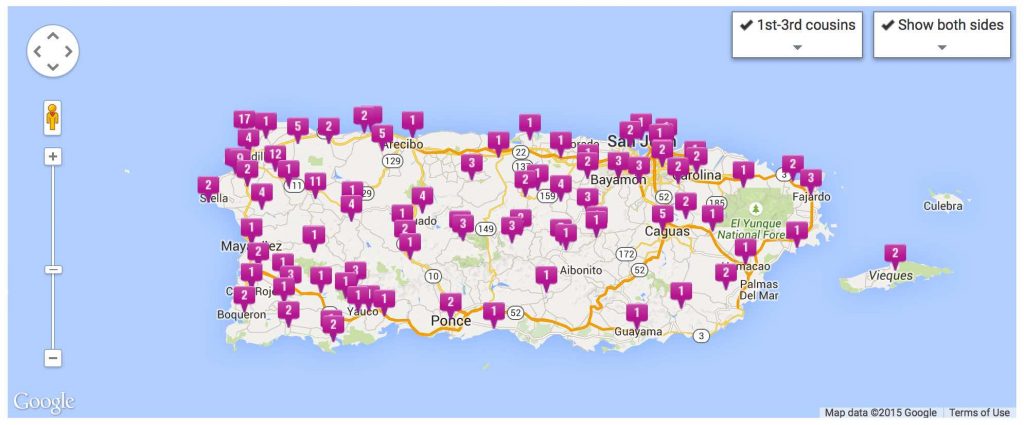

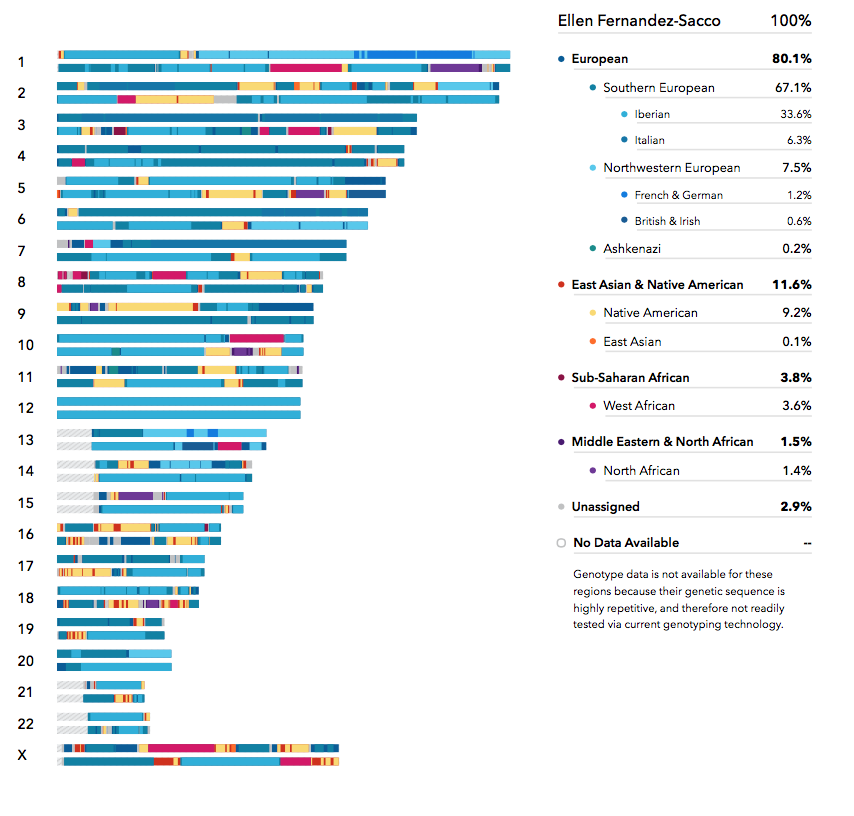

Looking at my own tree, I have distant connections to the Benejam via marriage to another slaveholding family, the Lorenzo de Acevedo. Even one of my recent atDNA matches points to this connection on FTDNA, and there are likely more 4-5th cousins out there, like myself, with genetic ties to both slaveowner and those they enslaved.

The Benejam originate in Menorca, among the smaller of the Baleáricos Islands. They arrived in Puerto Rico during the 18th century, and became an important family in Moca, owning land and people that they freed after 1870. Cristobal Benejam purchased Juan from the parish priest Pbo.Jose Balbino David, who functioned as a local small slave dealer during the 1850s, buying and selling people to various individuals.[5]

Living Transactions: currency & human devaluation

During the nineteenth century, the Puerto Rican economy struggled with a mistrust of paper currency, rudimentary banking practices and a lack of coinage. What was used were pesos macuquinos (‘Cob coin’), a silver coinage removed from circulation in Venezuela, and instead, was in circulation on the island for nearly a half century, without a real banking system. This meant real money was scarce. [6] Within this plantation economy, enslaved people were sold and the income from their sale was used by slaveholders to pay their own taxes and bills. The scant availability of cash on the island suggests the enormous difficulty of the situation that the enslaved faced in raising funds to purchase their own freedom, and the deep anxiety over maintaining family with the threat of sale and displacement constantly looming. Regardless, many continued their attempts and strategies to push for freedom.

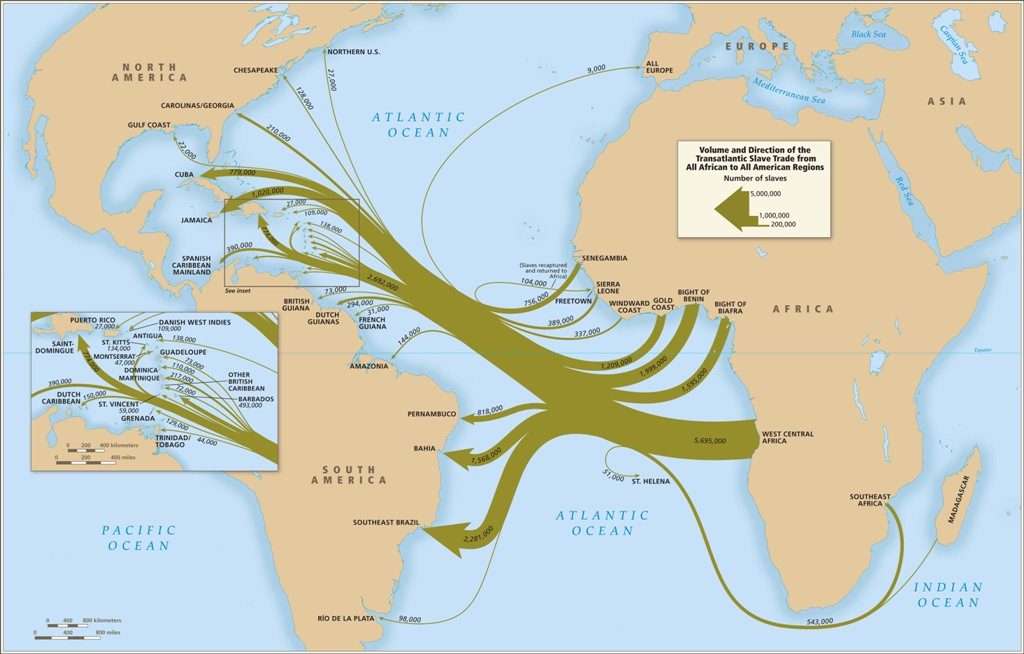

Among the slave owners were Gonzalez, Perez del Rio, Benejan, Soto, Lopez, Vasquez, Salas, Suarez Otero, and de la Cruz; some entries give information on previous owners, and together with other notarial entries, one can glean details on the places those held in slavery by them lived and worked. The location of origin for most of the persons listed below was Puerto Rico, although some came from Costa Firme, Venezuela, the Dutch Caribbean islands, and Santo Domingo. The official inscribing the documents into the books was the mayor or Alcalde ordinario d.Casimiro Gutierrez de Canedo, as there was no official royal notary in Moca to record these acts between 1848 and 1852.

Gaining Freedom

Almost all the persons listed paid for their freedom, with five cases granting unconditional freedom with no money involved. Aside from these cases, 32 pesos was the lowest price and 300 pesos the highest. The total amount spent by the enslaved for their freedom was 1,947 pesos macuquinos. Depending on the calculation, this may be equivalent to just over $10,600 US according to the Consumer Price index or $10,900 US in relative wages in today’s money. [7]

Given the scarcity of cash at the time, it is an astounding figure that illustrates the extractive nature of slavery that POC were forced to navigate in mid-nineenth century NW Puerto Rico.

Letters of Freedom, Moca, Puerto Rico, 1848-1852

20 Jan 1848: Pedro Gonzalez, 28, criollo (born in Puerto Rico), single, bought his freedom for 32 pesos from d. Faustino Perez del Rio. F1

24 Jan 1848: Eugenio, 26, criollo (born in Puerto Rico), single, bought his freedom for 250 pesos silver from d. Maximo Gonzalez. F2

8 Feb 1848: Mauricio, 1 1/2, freedom bought by his mother Monserrate for 25 pesos from d. Juan Jimenez. F5v

8 Jun 1848: Candelaria, bought her freedom for 68 pesos from d. Cristobal Benejans. F17v-18

24 Jul 1848: Ramona, 7 mo., mother Maria Encarnacion bought her freedom for 37 pesos from d. Alberto de Soto. F48v

24 Jul 1848: Tomasa, 35, criolla (born in Puerto Rico), mulata, servant her freedom purchased for 300 pesos from d. Felix Lopez and his wife Petrona Vega. Tomasa was “born in the home of another of their slaves named Paula.” F23-23v

24 Jan 1850: Maria Ylaria o Isidora 2, born on his property, mother Maria Candelaria bought freedom for 70 pesos from d. Cristobal Benejam. F25v-26.

8 May 1850: Felix, 60, ‘natural de la isla’ (born in Puerto Rico) light mulato, for good services, granted freedom from d. Manuel Salas’ (-1850) will. F48v

8 Aug 1850: Lorenzo, who resides in Moca bought freedom for 300 silver pesos from Jose de la Cruz of Lares, who bought him from Juan, Antonio y Francisco de la Cruz. F100-100v

15 Oct 1850: Maria de los Angeles, 26, servant, bought her freedom for 300 pesos from d. Maximo Gonzalez. F128-129

22 Nov 1850: Maria de la Encarnacion, servant, bought her freedom for 100 pesos maququinos from d. Alberto de Soto. F151

9 Apr 1851: Marcos, 70, born Santo Domingo, dark skinned, bought his freedom for 60 pesos from d. Francisco Roman. F52v-53

16 Aug 1851: Matias, 60, Dutch, tall, chocolate color, graying hair, regular front with honey colored eyes, thick nose, large mouth, bushy eyebrows, to be granted freedom for his service, obedience, respect and honor upon the death of da. Rosalia Perez. F170v-171

16 Aug 1851: Prudencio, 8, reddish color, passing hair, regular appearance, honey colored eyes, wide nose, small mouth to be granted freedom upon of da. Rosalia Perez. F171-171v

16 Aug 1851: Catalina, 40, single, reddish black color, passing hair, sad eyes, thick, wide nose wide mouth and bushy eyebrows, for good conduct from the first day, with honesty and activity proper to a slave to her masters to be freed upon the death of da. Rosalia Perez. F171v-172

29 Aug 1851: Teresa, 56, single, mulato, to compensate for her distinguished services with real love and constancy to be granted her freedom by d. Manuel Morales. His son d. Enrique Morales signed as his father did not know how to write. F176v-177

27 Oct 1851: Pedro Pablo, 30, born in Puerto Rico, single, mulato, reddish hair, regular appearance, regular nose, brown eyes, regular mouth and scant beard, purchases his freedom for 200 pesos maququinos from from d. Pedro Vargas. F227-227v

23 Dec 1851: Encarnacion, 40, born Costa Firme, Venezuela, given freedom for her good service via the will of d. Vasquez, via son d. Leonardo Vasquez. F304v

24 Jan 1852: Maria de la Cruz, 14 criolla (born in Puerto Rico), single, light mulato, household servant, straight hair, small round face , black eyes, properly placed nose, regular mouth, freedom purchased by her father Pedro Cordero for 205 pesos maququinos from d. Jose Suarez Otero, deceased, via da. Teresa Cordero, his widow. F20-20v

References

[1] Michael Zeuske with Orlando García Martínez & Rebecca J. Scott. “Estado, notarios y esclavos en Cuba. Aspectos de una genealogía legal de la ciudadania en sociedades esclavistas.” Cuba. De esclavos, ex-esclavas, cimarrones, mambises y negreros. 102-165; Table 7.2 Population Increases by Race, in Olga Wagenheim’s Puerto Rico: An Interpretive History, p. 151 for 1846 lists a total population of 443,139; 216,083 White; 175,791 Free People of Color, and Slave at 51,265. By 1869, this number drops by -12,196 to 39,069 persons. Olga Jimenez de Wagenheim, Puerto Rico: An Interpretive History, from Pre-Columbian Times to 1900. NY: Marcus Weiner Publishers, 1998.

[2] Cartas de emancipación de esclavos compiled from Carlos Encarnacion Navarro, Transcription, Caja 1444, Serie Aguadilla, Pueblo Moca, 20 Jan 1848-31 Jan 1852, Fondo de Protocolos Notariales, Archivo General de Puerto Rico. Translations and extracts are my own.

[3] Antonio Nieves Mendez, Historia de un pueblo Moca, 1772-2000. Lulu.com 2008, p.146. Ref. Caja 1444, f4.

[5] “3556. Paula, 29, hija de Juana.” 1 Mar 1870. Registro de Esclavos, Moca, Dist. Aguadilla, Caja 4, FHC Film 1511797.

[6] Pedro Damian Cano Borrego, “La moneda macuquina Venezolana y su circulación en Puerto Rico.” Numismatico Digital, Marzo 2017, Edition 114, 27 agosto 2017, http://www.numismaticodigital.com/imprimir-noticia.asp?noti=6383 . Accessed 27 Aug 2017.

[7] It seems the varying prices listed estimate both value as property and potential labor value, will be looking into this further. Values from two sites, Measuring Worth, https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/spaincompare/relativevalue.ph and Currency converter Euro to US Dollar: https://coinmill.com/EUR_USD.html#EUR=8991