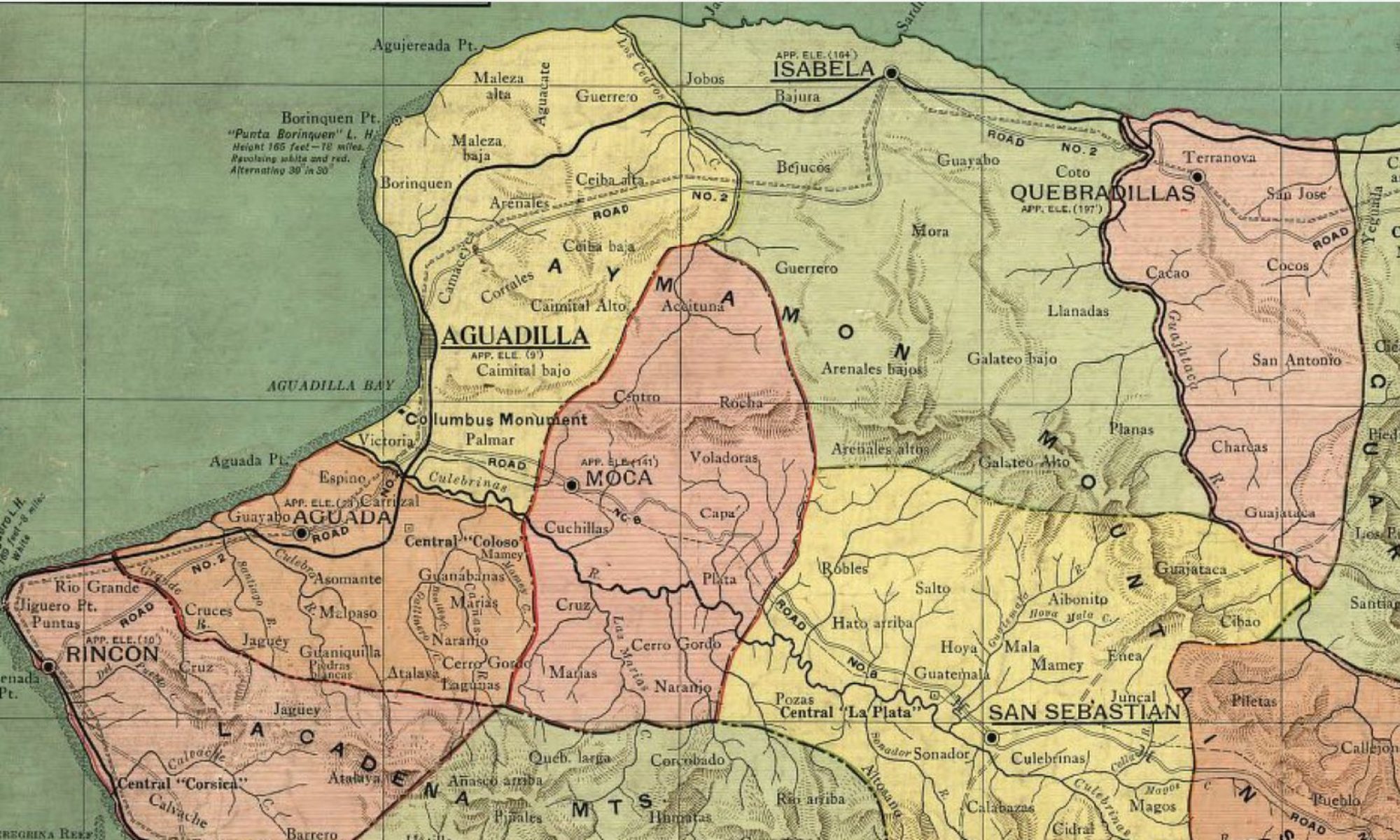

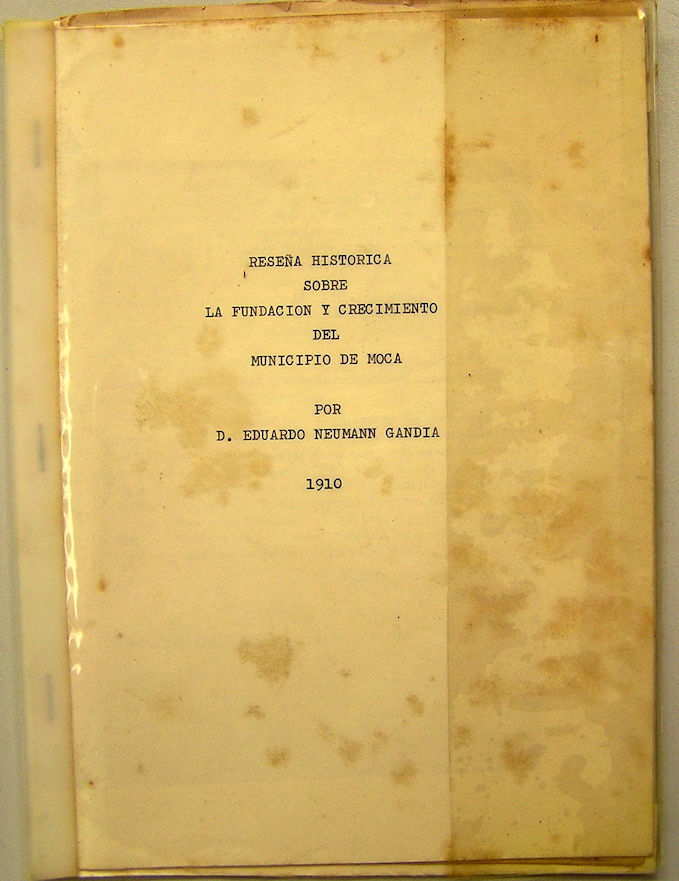

Two decades ago, I was in the Special Collections of U InterAmericana looking at their Herman Reichard Collection, where I photographed historian Eduardo Neumann Gandia’s Resena historica sobre la fundacion y crecimiento del municipio de Moca of 1910. Despite the homemade cover, this was one publication of at least two tracts by Neumann Gandia that served to circulate a brief history of a municipality.

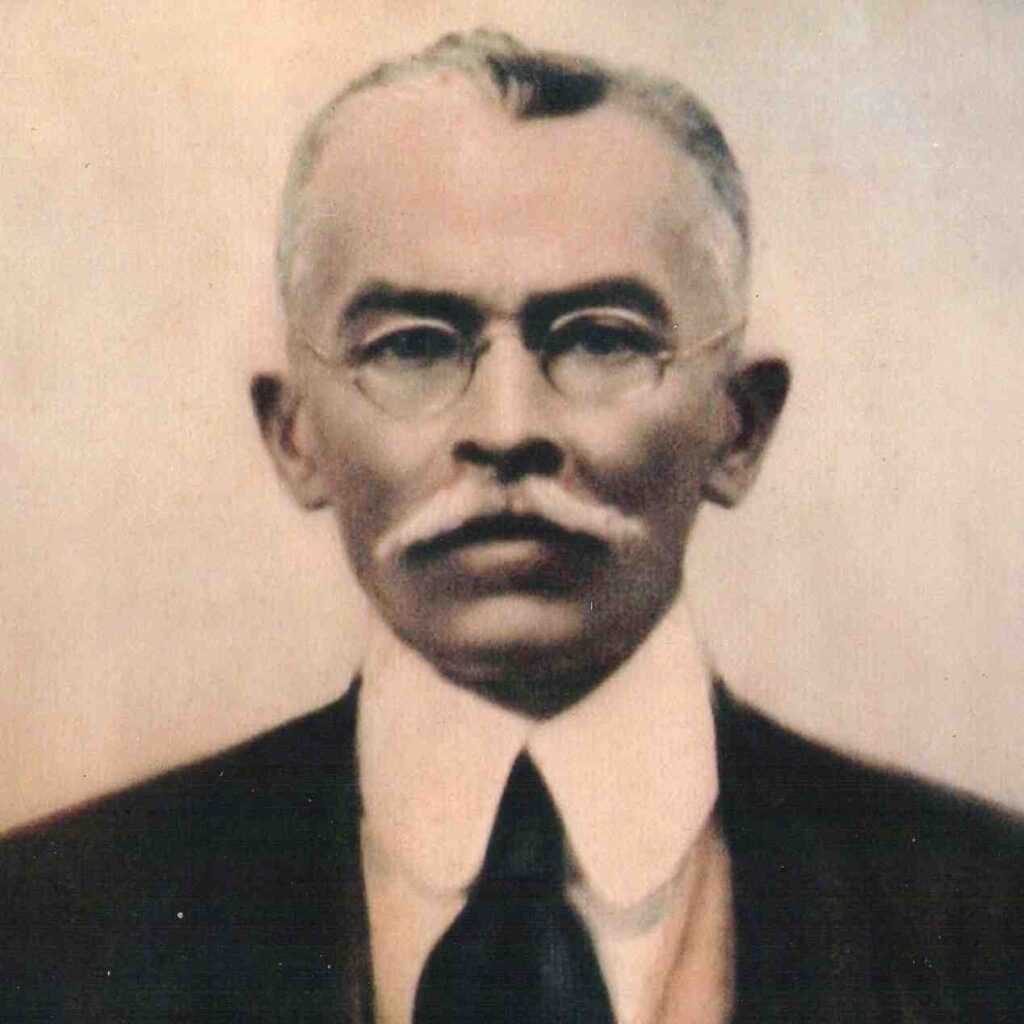

Eduardo Neumann Gandia (1852-1913)

It’s a brief 11 pages, taken from a larger work as can be seen from the numbered pages 79-90. There’s no mention of what the original text was. Nor do can we tell the entire volume was by a single author, or if it was a collection that includes multiple municipalities. He published his two volumes of Benefactores y hombres notables de Puerto-Rico: bocetos biográficos-críticos con un estudio sobre nuestros gobernadores generales, in 1896 and 1899, which contained mini-biographies of figures in government and business.

Herman Reichard Esteves (1910-2005), who preserved this pamphlet and other archival materials, was a librarian and professor based in Aguadilla. He was an avid genealogist whose work continues to inform many today, and which Dra. Haydee Reichard is making available through the Archivo Digital Nacional de Puerto Rico ADNPR.net. I made photographs of Neumann Gandia’s work, and (over 110 years later) ran it through an OCR program to make a PDF from the images.

You can download the pamphlet from the link at the bottom of the page.

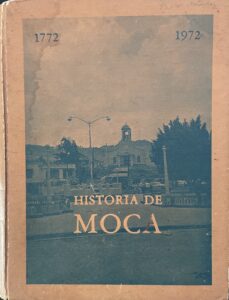

1972: Historia de Moca 1772-1972

This text was the basis for the 1972 bicentennial publication, Historia de Moca 1772-1972, produced by Sociedad Civico-Cultural Pro-Conmemoracion del Bicentenario de Moca, Inc. Published by the Dept de Instruccion Publica, Estado Libre Associado de Puerto Rico, both organizations spoke to a particular moment of identification on local and state level, and a recognition of a shared history that extends to the eighteenth century.

There is no mention of the fact that Moca is an indigenous name, nor of any survival in these pages. Additional information builds out Neumann Gandia’s brief history and benefits from photographs of the location and personages, as for the biography of the educator Adolfo Emeterio Babilonia Quinones (1841-1884). He married into the Yturrino family, whom i’ve written of in a previous post.

Cover, Historia de Moca 1772-1972. Edición bicentenario. Collection of the author.

Cultural Memory, ancestors & what gets overlooked…

The purpose of Neumann Gandia’s text and its later iterations was on the importance of a cultural memory. These local histories can be crucial for creating the microhistories of our ancestors on different parts of the island. This is not the same as a building a romanticized story of the past. Instead the intent is to write to reflect the struggle to live, have families or not, to stay or to go, to become part of groups that yielded forms of support, or produced a variety of creative expressions.

The 1972 book devoted two pages to mentions of enslavement: La Esclavitud Negra:(breves anotaciones) en Moca. There are a couple of paragraphs detailing the presence of enslaved people in Moca since its founding. Quoted is the 1945 interview by Luis M. Diaz Soler in Historia de la esclavitud negra en Puerto Rico. This excerpt acknowledges the experiences of Leoncia Lasalle and her daughter Juana Rodriguez Lasalle under bondage. Looking back at Resena, for early Puerto Rico, Neumann Gandia simply elides the topic (save for the statistics) yet the system of enslavement permeates the economic activity of the era he describes, the 1840s on.

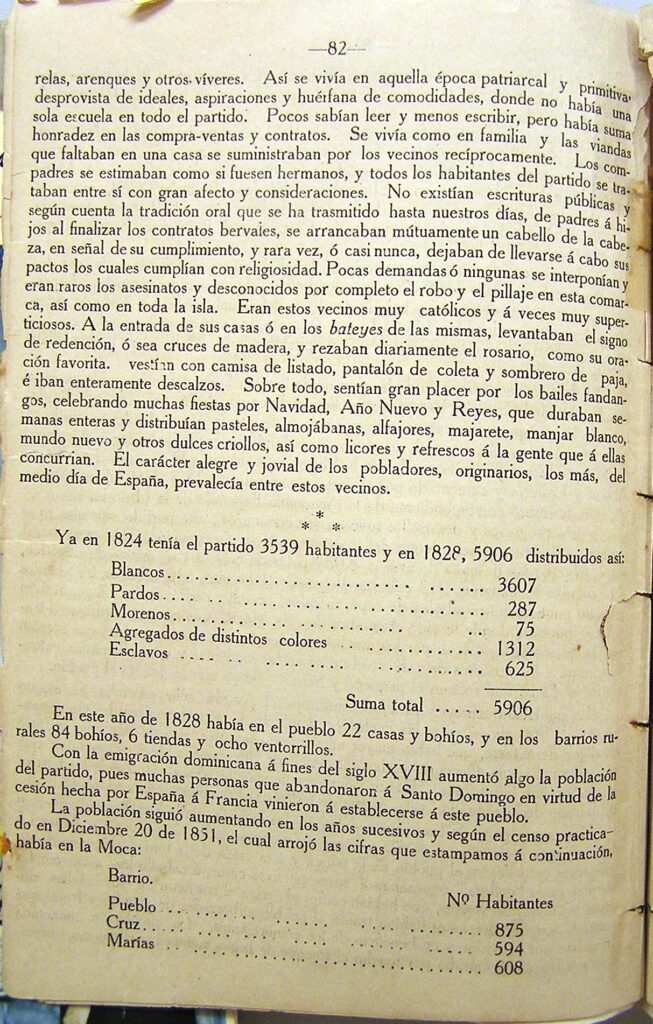

Neumann Gandia, Resena historica de sobre la fundacion y crecimiento del municipio de Moca Page 82

Neumann Gandia’s Moca of the 1840s, p.82

“…Así se vivía en aquella época patriarcal y primitiva desprovista de ideales, aspiraciones y huérfana de comodidades, donde no habia a sola escuela en todo el partido. Pocos sabían leer y menos escribir, pero había suma honradez en las compra-ventas y contratos. Se vivía como en familia y las viandas que faltaban en una casa se suministraban por los vecinos reciprocamente. Los compadres se estimaban como si fuesen hermanos, y todos los habitantes del partido se estimaban entre si con gran afecto y consideraciones. No existían escrituras públicas y según cuenta la tradición oral que se ha trasmitido hasta nuestros días, de padres á hijos al finalizar los contratos bervales, se arrancaban mútuamente un cabello de la cabeza, en señal de su cumplimiento, y rara vez, ó casi nunca, dejaban de llevarse á cabo sus pactos los cuales cumplían con religiosidad. Pocas demandas ó ningunas se interponían y eran raros los asesinatos y desconocidos por completo el robo y el pillaje en esta comarca, así como en toda la isla. Eran estos vecinos muy católicos y a veces muy superticiosos. A la entrada de sus casas ó en los bateyes de las mismas, levantaban el signo de redención, ó sea cruces de madera, y rezaban diariamente el rosario, como su oración favorita. vestían con camisa de listado, pantalón de coleta y sombrero de paja, é iban enteramente descalzos. Sobre todo, sentían gran placer por los bailes fandan-gos, celebrando muchas fiestas por Navidad, Año Nuevo y Reyes, que duraban semanas enteras y distribuían pasteles, almojábanas, alfajores, majarete, manjar blanco, mundo nuevo y otros dulces criollos, así como licores y refrescos á la gente que á ellas concurrian. El carácter alegre y jovial de los pobladores, originarios, los más, del medio día de España, prevalecía entre estos vecinos.“

“That is how life was in that patriarchal and primitive time devoid of ideals, aspirations and orphaned of accommodation, where there was not a single school in the entire region Few knew how to read and even less how to write, but there was honesty in sales and contracts. One lived as family and the vegetables that one household lacked was taken care of by the locals reciprocity. Godfathers treated each other as if they were brothers, and all the inhabitants of the area regarded each other with great affection and considerations. There were no public documents and after oral tradition that has been transmitted to the present, of fathers and sons finalizing their verbal contracts, each would pull a hair from the other’s head as a sign of fulfillment, and rarely, or almost never, left from taking to completion their pacts, which they accomplished religiously. Few demands or none were and rarely were there murders or unknowns who robbed and pillaged in this county as in the rest of the island. These inhabitants were very Catholic and very superstitious. At the entry of their homes or in the bateyes of the same, they raised the sign of redemption, that is to say, wooden crosses and daily recited the rosary as their favorite prayer. They dressed with striped shirts, canvas pants , a straw hat and went entirely barefoot. Above all they were greatly pleased by the fandango dances, celebrated many parties through Christmas, New Years and All Kings Day, that lasted entire weeks, and distributed pasteles, “almojábanas, alfajores, majarete, manjar blanco, mundo nuevo” and other local sweets, along with liquor and refreshments to those to whom they agreed with. The happy and jovial character of the original founders, more from the middle age of Spain prevails among these locals…”

Neumann Gandia lays out a different world for the early nineteenth century. His was not an inclusive history, and the only cultural source recognized is European. AfroIndigenous or African cultural survivals or influences are not mentioned. This was instead a peasant society composed of a superstitious and illiterate populace prone to violence, whose ‘happy character’ is simply an expression of early Spanish culture. Look at those numbers though on p.82. Taking the categories of free and unfree together, the 2,299 BIPOC population is significant yet has no role in the historical scenario he sketched above.

The fact is that the island was a process of settler colonial society, with a system that required violence and the use of force to control the enslaved and sharecroppers ‘of various colors’ within a stratified society. Born in 1852, slavery shaped Neumann Gandia’s world. Freedpeople were very much around in 1910, and the process of emancipation terminated in 1886. Also interesting is that Neumann Gandia’s collection of Taino bird effigy bowls was purchased by Jesse Walter Fewkes. This remains for us to discuss in understanding our ancestors lives today and their world.

The best history of Moca is Antonio Nieves Morales’ Moca 1772-2000: Historia de un pueblo (Lulu.com, 2008). Nieves Mendez’ work is groundbreaking as a full history, one that includes tables listing enslavers and the enslaved, and his own connection to this past, via his family history.

Miguel A. Babilonia Talavera, Alcalde de Moca

Lost is the original cover and the introduction to the section on Moca, a message by the mayor, Miguel A. Babilonia Talavera (1867-1947) who became Alcalde in 1899, and again from 1905-1910. He is my great uncle, brother to my great grandfather Ambrosio Alcides Babilonia Talavera (1860-1951), who I knew from my mother’s recollections of her childhood there.

He served as mayor after the annexation of Moca from Aguadilla took place in 1905. On pages 50-51, the 1972 Historia de Moca volume reproduces part of page 79 from the Neumann Gandia pamphlet as “Don Miguel A. Babilonia se despide de sus conciudadanos” written in December 1910.

I want to express my deep thanks to all the members of the Babilonia family and their descendants, and members of SAMocanos for sharing their information and photographs with me over the years. I especially want to thank my cousin Gaspar Babilonia, for sharing his collection of his grandfather’s photographs.

Now digitized images of ancestors and their communities populate a variety of places on social media, another way that descendants can connect to their past. Neumann Gandia’s work is but one expression of this from over a century ago.

You can download a copy here: Eduardo Neumann Gandia’s Resena Historica de Moca