That diasporic feeling

There is no one place or time when diaspora occurs…it is a perpetual space of change and displacement. An awareness. It’s a process I share with many, whether by blood, place or experience, with locations linked by oceans and shaped by the relentless squeeze for money and power.

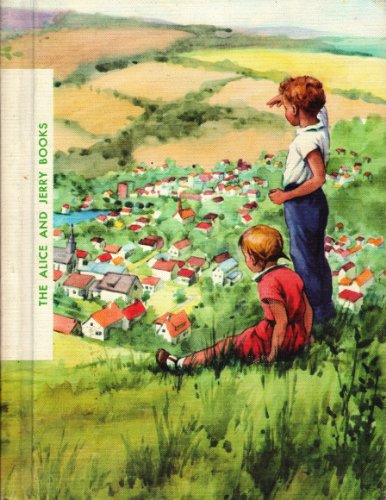

How we understand this process has a lot to do with the narratives fed to us as children. Here’s a memorable text whose social cues seemed sketchy to me in grade school.

Friendly Village

As a child in the early 1960s, the most confusing book I’ve ever encountered was an assigned second grade reader by Mabel O’Donnell, entitled Friendly Village. I was switched into second grade mid-year, since I read at a 6 grade level thanks to my mom.

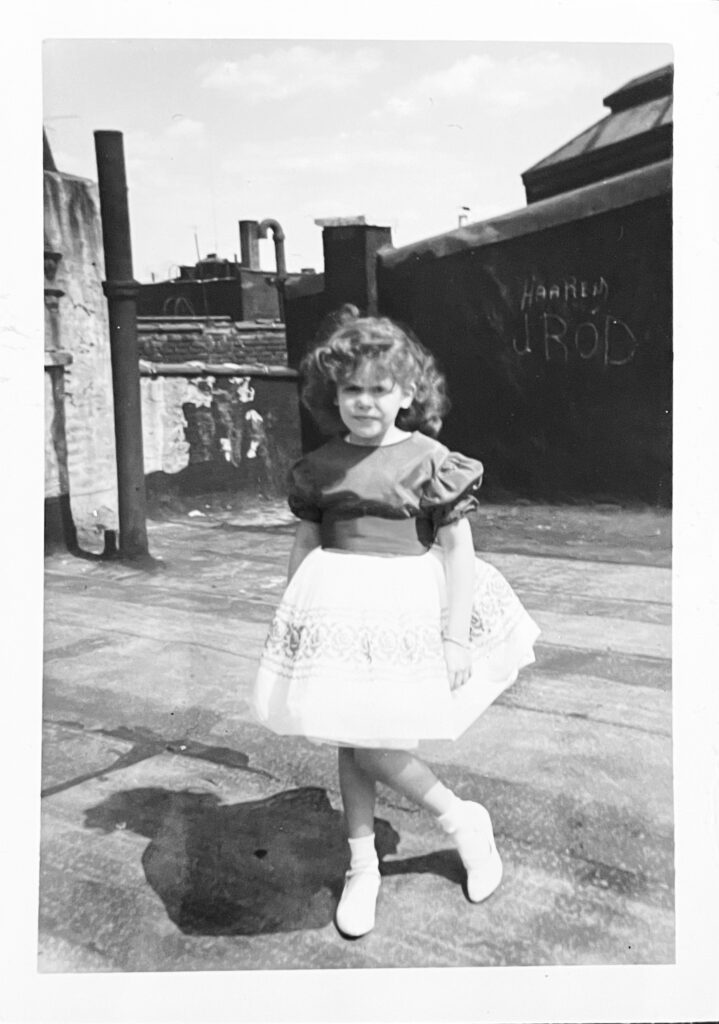

Nothing in the book seemed to jive with what I knew of the world in the south Bronx. For us, landscape vistas were restricted to a small outcropping of glacial rocks, some maple trees and wildlife— pigeons and the large rats in St Ann Park, all four city blocks of it.

Where we lived then was composed of blocks of tenements built at least a half century before my birth, dark narrow buildings whose stoops and entrances varied slightly from structure to structure — brick fronts, embellished by fire escapes above the street, each four to five floors tall, with four apartments to a floor. These buildings loomed before my small frame.

Buildings of memory

Most tenements were built in the first years of the 1900s, the metal ironwork that once flanked the stairs collected in the 1940s for the war effort. This left most buildings with a bare stoop in front.

Air shafts, then a recent innovation in 1900, defined the view in our apartment. from one window, one saw sets of white framed glass portals to other living spaces, surrounded by brick and crossed by laundry lines. Down below was the small concrete footprint of the space. Then, from early spring to late fall, these were full of bed sheets and tablecloths, shirts and underwear put out to dry. We never made any experiments to test gravity or my parents patience.

Tenements on Fox Street

To my small body, this tenement and neighborhood that surrounded it on Fox Street it all seemed like an enormous urban site, full of adults and rooms with a million different stories. Manhattan was even bigger.

Once inside, to reach our apartment, everyone made their way over white stone steps, climbing while holding on to a painted rail, inset into the top of cast iron balusters. The rail was coated in layers of thick enamel paint applied over many years. This smooth yet pebbled texture melted on the surface of the rail that linked the building’s floors and landings.

Each step was made of pale, white-gray marble or soapstone, worn down at the center, a saggy appearance that testified to the movement of thousands of footsteps over its surfaces, a bit worn away with each step.

Every floor held a set of relationships, that ranged from the legal to inappropriate. parents, newborns, lovers, strangers who left traces on the pages of the 1920-1950 census. My paternal grandparents lived in another tenement nearby, finally being able to settle down after the multiple moves during the Great Depression, heralded by the birth of my father.

Tenements were never part of the landscape of Friendly Village, and Alice and Jerry never went to such places, nor did they go to play in the trash strewn spaces behind them. The South Bronx was different then. The entrances of the buildings on each grey and grimy block had stoops once bordered with ironwork. This was removed, molten down for the WW2 effort, and never replaced, leaving large holes and orphaned bolts that told of phantom parts. The now plain steps lead to the doors, some of them arching over the entryway to a basement workshop or apartment and storage rooms that ran along the length of the building.

The Newsstand

On the corner, it seemed a sizeable amount of steel escaped the wartime scrap heap and was a featured element of the commercial space of the corner newsstand. The store sat atop a metal sidewalk, raised about 3-4 inches off the concrete, its surface pierced with small round glass disks trapped in the metal pentagonal grids, to provide light for a mysterious space underground. This dark, almost green black metal surface surrounded the store, and clanged as one stepped up and walked on it, its own alert system that let the owner know a customer approached.

The newstand rack was itself an accomplished bit of welded heavy steel plate with supports for shelves that held several daily and weekly newspapers just outside of its tiny space. inside the actual store was cramped and crowded with racks of magazines on its walls, comic books, boxes of cigarettes and chewing gum. Just enough space for one clerk to sit behind the counter, next to a heater in winter and a small fan in summer.

Gum of gums

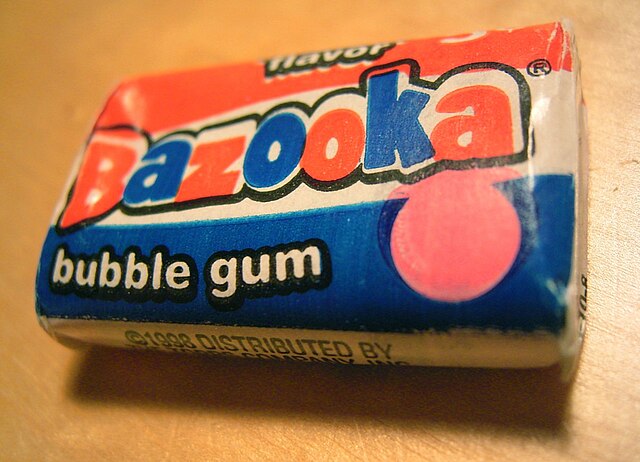

On the small counter next to the cash register, sat an open box of Bazooka gum for sale. For our two cents, we bought a piece of gum named for a rocket launcher, the brand name Bazooka revealing the proximity of recent wars to the lives of children who bought them, from World War 2 to Korea, and afterwards Vietnam. These small packets were extremely firm (the staler, the harder) a segment of sugary pink chewing gum with an indented line down the middle for sharing or apportioning. It made a dentist visit much more likely.

Its dusted sugar surface was bound by a folded Bazooka Joe comic in 3 colors, that to our young eyes featured seemingly adult men exchanging pointless, corny lines in several tiny frames on a small sheet of shiny waxed paper. This gift arrived under a larger red and white wax paper wrapper w diagonal lettering that announced ‘Bazooka’.

It took work to chew. it was a product that simultaneously allowed one to both blow bubbles and to dissolve one’s tooth enamel. If the gum was stale, masticating took twice as long to coax it into a bubble and create annoying, cracking noises.

Bazooka was a different than Crawford’s Breath Gum, lovely purple pieces in a flat silver cardboard box with scrolling black letters. My mother loved them and almost always had a box in her handbag. Later we went for sticks of gum, peppermint but never spearmint. We left Bazooka behind.

Creative impulses

At school or near these institutions, we noticed that the uses of gum extended to cheerful decoration, witnessed on the undersides of chairs and desks or on the lengths of telephone poles that became colorful, textured repositories of various brands, processed by teeth of children and teenagers. Such sites were only to be augmented with one’s own bit of masticated gum, and not to be touched by fingers.

Return to the Friendly Village

But back to the Friendly Village, a book that only sowed more confusion as I read its pages. It featured puzzling details– Fathers who wore glasses, a suit and tie and carried a briefcase. I knew no one like that. My dad worked first as a baggage handler on the railroad and next for the Metropolitan Transit Authority when he finally passed the test for the MTA in ventilation and drainage. When we were little we only knew he was somewhere in the bowels of NYC, traversing endless miles of tunnels and small rooms crammed with the equipment that made it possible to see and breathe on the subway. He worked two jobs at one point, so he was hardly at home.

My grandparents lived just a few blocks away, my grandfather drove taxis or school buses for work and could barely read a newspaper. This was probably because of dyslexia, which added another layer of difficulty to everything he navigated stateside. He had a tremendous memory though for numbers and memorized lists of Bolita digits, no paper to find. My mother worked in various factories in Manhattan and Brooklyn in the 1940s to 1950s before she had us, and she was 14 when she got her first job.

Details details

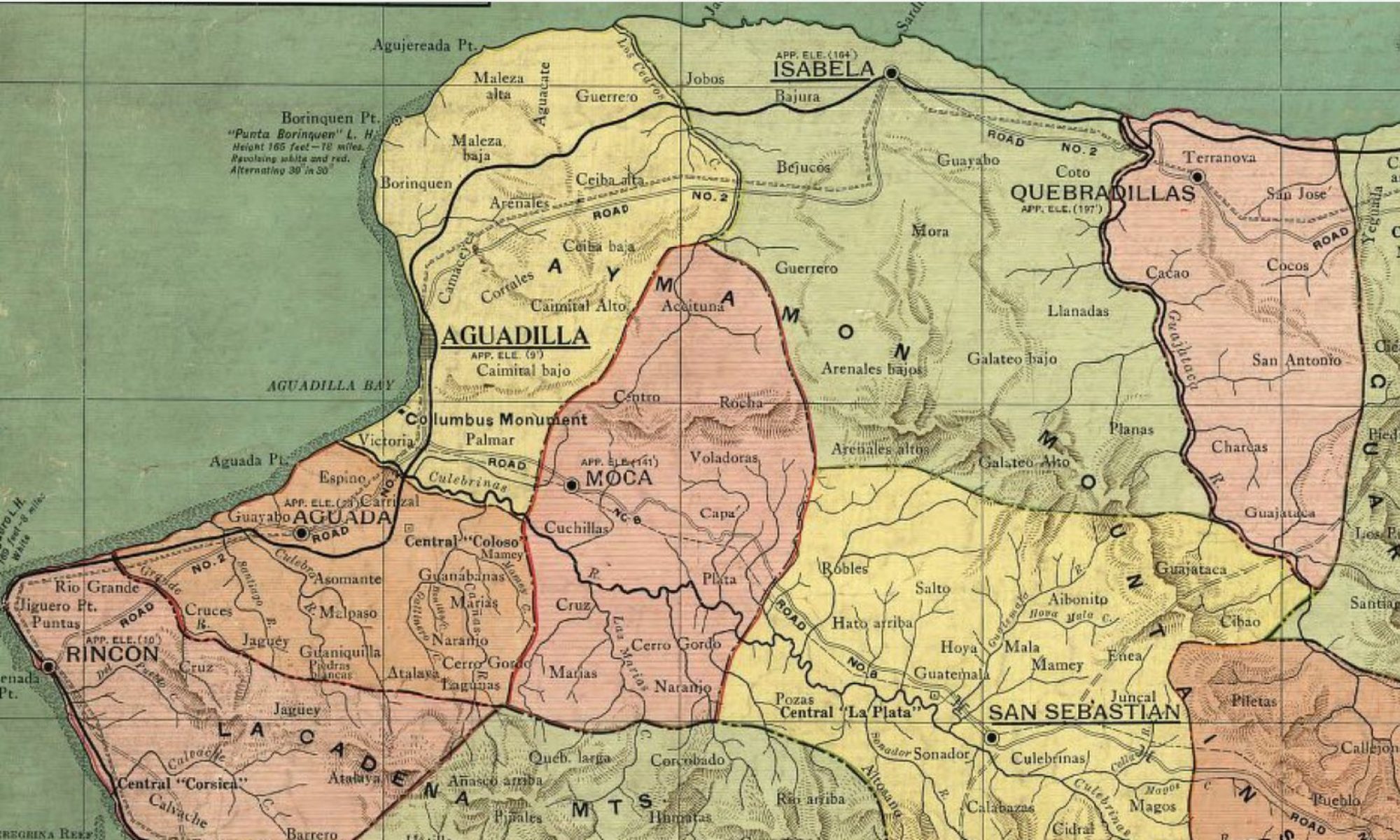

As jarring a read as the Friendly Village was, there was no village, no cows and no farmers in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. instead, a steadily growing number of Puerto Ricans were packing a landscape created at least a half century before, at the turn of the century just after the Spanish American War.

We lived in a walk up apartment and there were no thatched roof houses anywhere nearby. The population of the Friendly Village was white and British, with pedigree dogs unlike the mutts that roamed our neighborhood in ragged packs.

Actually, we were the ones the locals feared, the Puerto Ricans born on the island and stateside, who occupied more and more apartments as the neighborhood aged and its former Jewish and Slavic inhabitants escaped to the suburbs. The book left me wondering about places like England, and what seems a high probability of being run out of a village if my family actually showed up there.

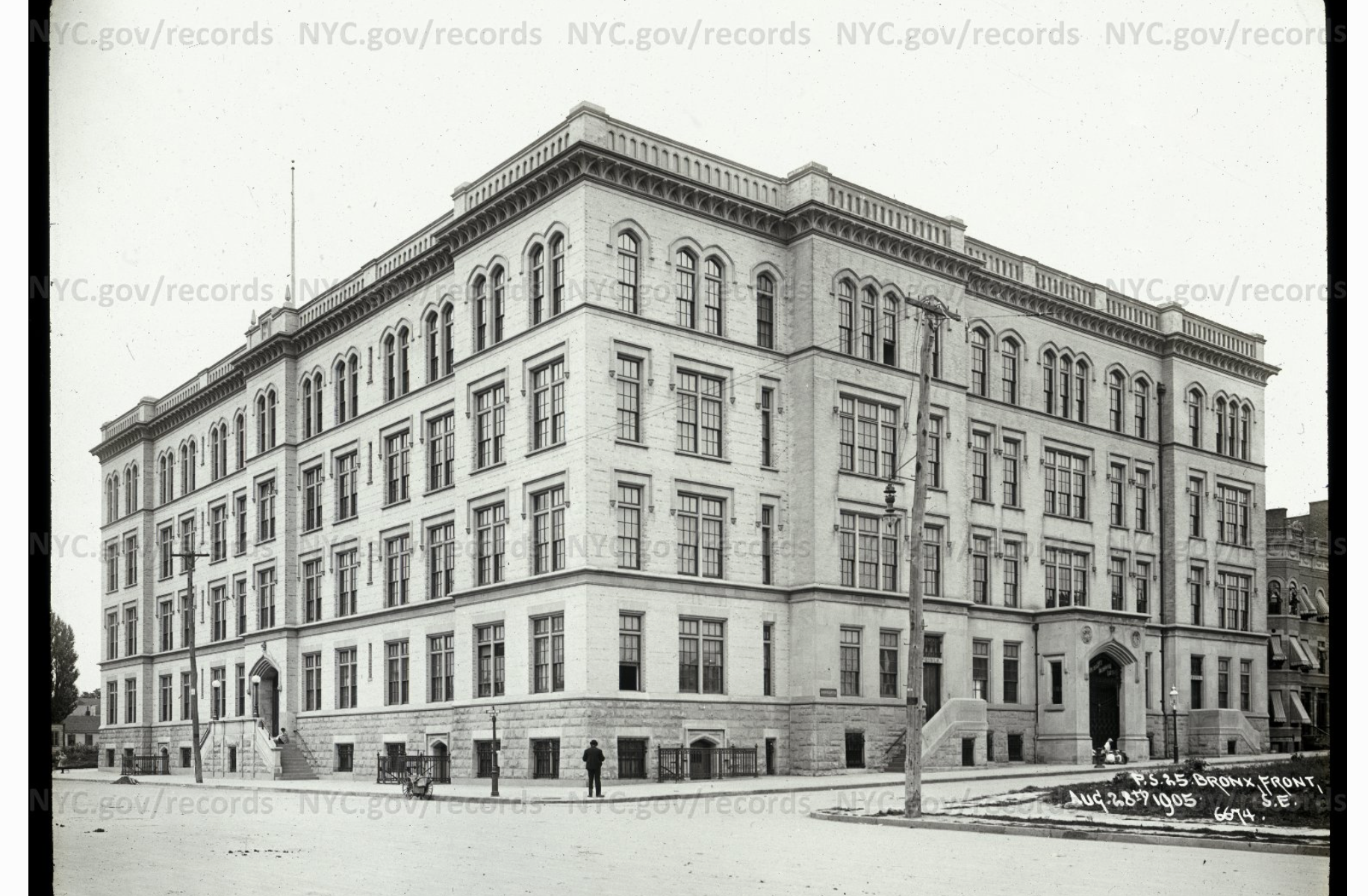

To School, PS 25

Each morning as my mother walked us to elementary school we were careful to step over the legs of the two young men of color, both junkies with their backs propped up against a building. As we walked, I stared at the thin stream of urine that led from between their legs down the sidewalk, over the edge of the milled stone curb and into the gutter. Occupied with their high, they failed to notice the proximity of the yellow water that stained their pants as it streamed out of them; neither did they acknowledge seeing us walk past. They didn’t go to school, nor did they appear in any school reader.

Fox Street became rougher by the year. When a man was shot in the head just doors away on the block, my father decided that was enough. He began searching for a house in another location, in Hollis, in the very distant and exotic borough of Queens.

We left the Bronx and the pages of The Friendly Village proved little help for understanding why I was called a Spic by whites fearful of our kind, nor of the girls who dropped an open container of milk on me on the stairs on Assembly Day, or those who decided to fight me in a group in the schoolyard. I was a white presenting skinny kid, a product of diaspora, settler colonialism & slavery, searching for a definition of self in books that didn’t acknowledge our blended existence. I kept reading.

Dick and Jane, the ideal white boy and girl featured in the reader’s pages taught me nothing about how the world worked, nor of the working class, or of the many peoples caught in the flows of diaspora that made up the city of New York in the early 1960s.

Decolonized spaces

Today we make our own villages, those safe spaces where we can reveal our fullest selves to survive and share our journey as best we can. It’s remarkable how one group’s joy can be rejected, but they can’t steal it. Brook Park, a place I visited in my childhood, is now the site where my Iukayeke holds its solstice ceremonies, and I connect, via technology.

We are still here.

Long gone, the buildings and streets of Mott Haven come back vividly in memory, places where my ancestors once tread as they made their way through the cycle of life.

QEPD May they rest in peace.

Seneko kakona