Oral history, Alex Haley’s Roots and the question of proof

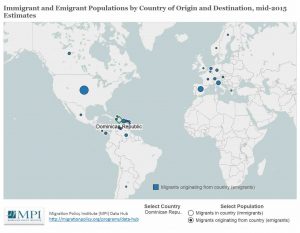

Change takes time. It can feel glacial when looking at the time frame for the development of genealogy for people of color in the US. As Nicka Smith recently reminded us in the video of Ep20b of BlackProGenLIVE on Talks Diversity in Genealogy and Family History, our path is difficult because a fundamental building block is oral history. [1] As she pointed out, ‘the problem of the color line‘ remains a very real one in genealogy.[2] I’m into understanding that context, and want to take an opportunity to look back at another decade’s work where the push for truth served to reinforce a boundary. The question of proof in genealogy always looms large. For examples of practice, don’t miss the list of blogs at the end of this post.

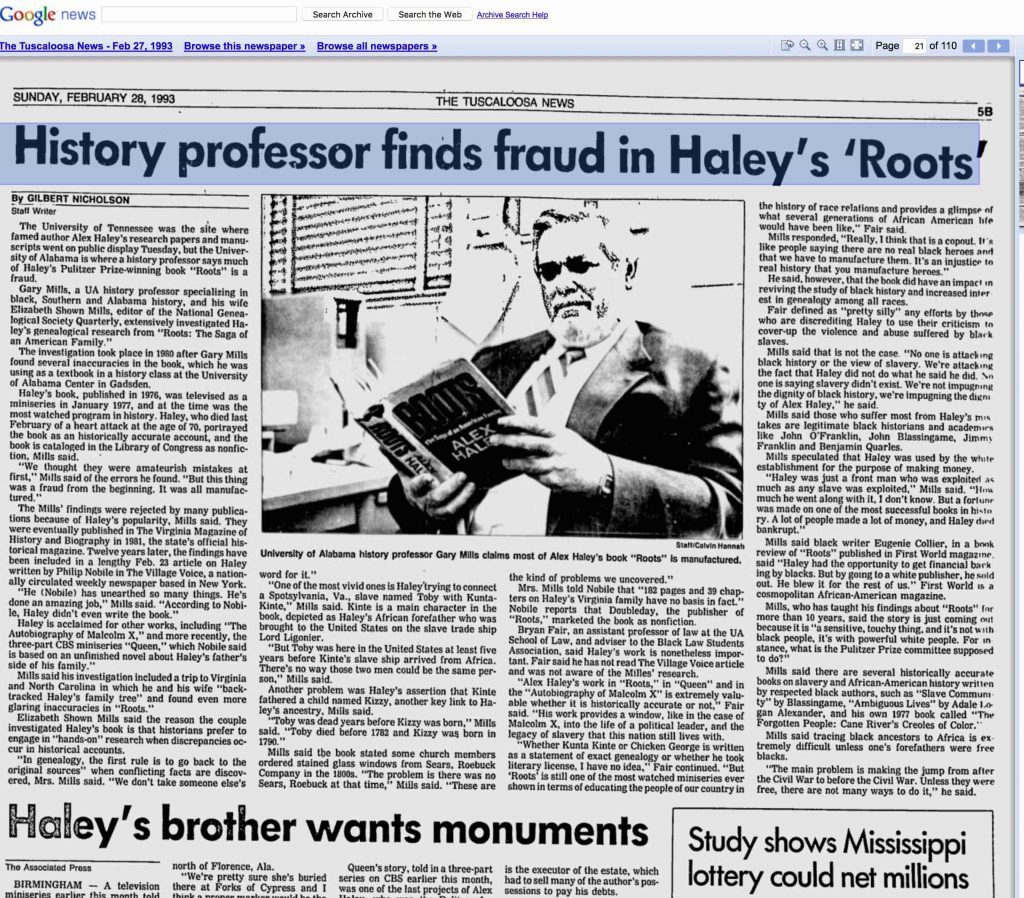

A quote from a 1983 article that contained a relentless takedown of Alex Haley’s book Roots: The Saga of an American Family, reveals the seams along which professional genealogy developed, some eighty years earlier. This split posits the document against the voice in oral history as the legitimate source of data. Thirty-three years ago, this genealogical work was an endeavor that missed the boat in its insistence on paper as the ultimate proof, and perhaps the location there is significant, as it came out of the deep South.

Facts, Claims and the Logic of Proof

The claim that ‘No ethnic group has a monopoly upon oral tradition or documentation, literacy or illiteracy, mobility or stability'[3] ignores the fact that enslaved people counted for chattel, that various populations were brought to labor in oppressive conditions here, and key is that most people of color were not party to creating documentation on their own behalf reflective of them as equal people with equal rights. This goes well beyond “superimposing racial divisions upon all aspects of life…”[4] and ignores that the struggle for civic recognition reaches back to the founding of the country. The fear expressed then, was that Haley’s book could constitute a ‘…delusion that encourages mediocre scholarship in the nascent field of Afro-American genealogy and relegates black family history to the academic dark ages from which Caucasian genealogy has already emerged…’.[5]

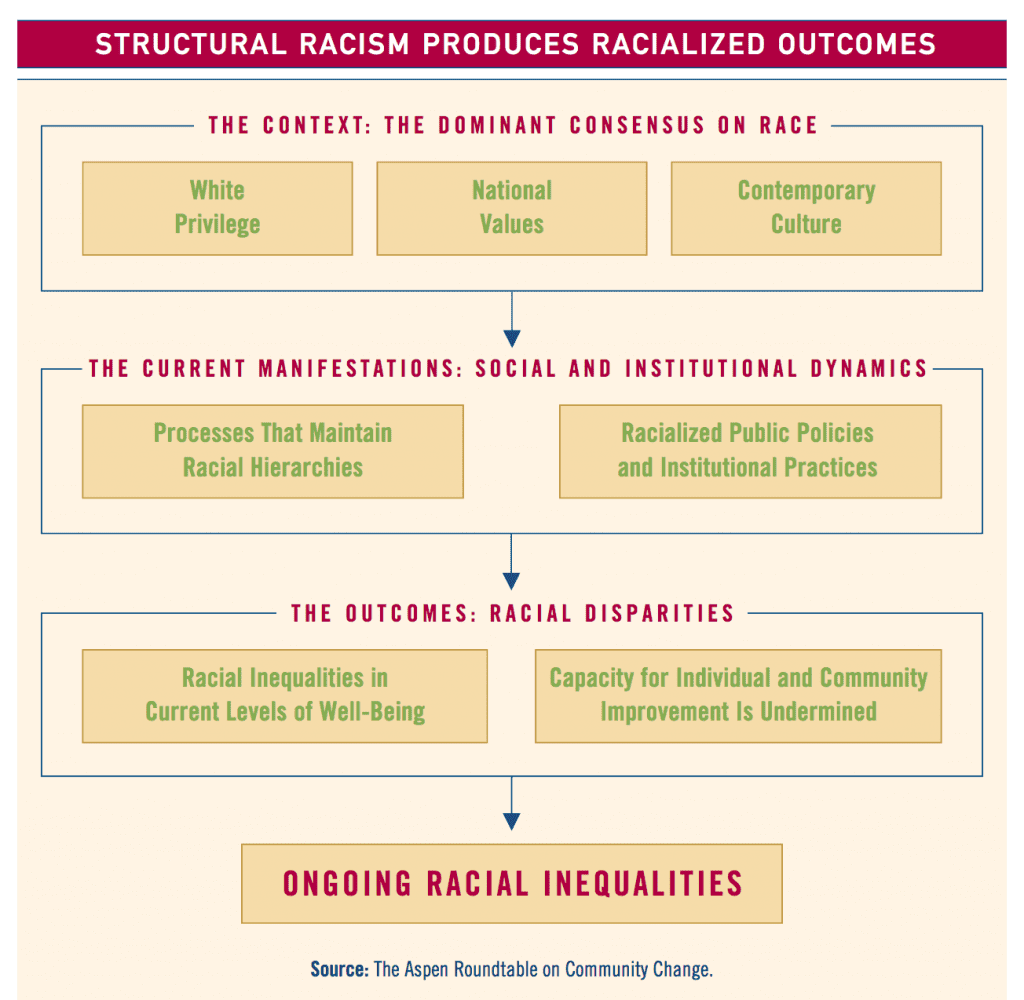

The problem is that this logic of ‘documentary proof as the only valid proof’ is part of the problem of structural racism, inadvertently or deliberately serving ‘to perpetuate social stratifications and outcomes that all too often reflect racial group sorting rather than individual merit and effort.’[6] To continue to claim this kind of proof as the only proof is an exclusionary exercise, in effect, one that insists on documentation within a context where one side holds the power, and is also one that perpetuates the gap between White Americans and Americans of color.

The following chart shows the interlocking parts of this system:

In essence, what we are witnessing today is a gradual process of desegregation within genealogy practiced in the U.S.

Strategies and Projects: Restoring Visibility & Developing Methodologies

Within the last two decades, genealogists in the field of African American genealogy have developed strategies for working with oral histories and published accounts and have successfully incorporated them within the Genealogical Proof Standard.[7] It follows the growth of historical, sociological and cultural work on various dimensions of the experience and process of enslavement, the development of various communities of color and difference as legitimate fields of inquiry. Now there is a growing awareness of combined efforts that defy simple ethnic or racial classification as with Marronage, those hidden and open maroon communities where people of African, Indigenous and varying admixtures stole themselves to, to gain self-determination. These historic episodes do not fit neatly into traditional genealogy and require new modes of recording, interpreting and disseminating data on the families of these communities.

Given the location, this work has neither a smooth or clear path to acceptance; for instance, one can look at the changes in the narratives offered by Monticello in the 1990s to the 2010s, with the recent Public Summit on Race and the Legacy of Slavery (Sep 2016) and the recent conference (Mar 2018) Interpreting Slavery Also important are the in-place interventions by Joseph McGill of The Slave Dwelling Project, and Michael J Twitty’s rising recognition as a culinary and historical authority with his blog Afroculinaria and his important book The Cooking Gene are gaining wider regard.

The summit, “Memory, Mourning, Mobilization: Legacies of Slavery and Freedom in America” would not have been possible without the oral histories along with the genealogical and DNA data collected by the Getting Word project at Monticello. As a result, descendants now have the opportunity to stay overnight through the Slave Dwelling Project. McGill continues to expand to new sites, to have important conversations as a group participates in a simple, visceral experience of sleeping in slave cabins.

Genetic genealogist Shannon Christmas is co-administrator of the Hemings-Jefferson-Wayles-Eppes Autosomal DNA Project and blogs on new tools and technologies for genealogy at Through the Trees. Robin R Foster has been blogging since 1985 at Robin Saving Stories. There are incredible collections of records and articles on Toni Carrier’s Lowcountry Africana, which covers the rice growing region across South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Or look at the work of my cousin, Teresa Vega in Greenwich, Connecticut regarding the Historic Byram African American Cemetery on her blog, Radiant Roots, Boricua Branches. (Scroll down for latest news)

Also consult the blogs of members of Black ProGen below (scroll down) to see more projects that take on various facets of genealogy to see examples of this broader change, and join us at BlackProGen LIVE twice monthly on YouTube.

Weighing what matters

I’m not saying that Alex Haley’s work cannot be analyzed for the errors it contains, but instead, that the weight of its context and the moment of its production mattered. Cited in The NY Times (and unnamed in a later article) was eminent Yale historian Edmund Morgan, who recognized that Roots was “a statement of someone’s search for identity… it would seem to me to retain a good deal of impact no matter how many mistakes the man has made. In any genealogy there are bound to be a number of mistakes.”[8] Morgan was the author of American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975), a title that points to the persistent contradiction in the founding of this nation. Overall, historians were not alarmed. Ultimately, Haley’s book proved more novel than fact, but more importantly, it captured the imagination of millions, inspiring many to pursue their own genealogy and family history. The stakes were high for claiming a rightful place as part of US history.

What Haley achieved at the time of the National Bicentennial was to tell a story of national import from a black perspective, as he hoped “his story of our people can help to alleviate the legacies of the fact that preponderantly the histories have been written by the winners.”[8]. One early reviewer of his work noted, “And so, he did write his entire story from the Black perspective which is sorely needed to connect the institutions and fill the void left by the omission of ‘objective’ white historians, the winners in the war of human degradation—slavery…. it is the cultural history laid bare upon the canvas of time devoid of the misconceptions and misinterpretations of a people rationalizing their sins against humanity.”[9]

Roots and its subsequent miniseries did not omit the range of violence perpetrated on a fully human people and claimed a historical place in the narrative of America. It countered a dominant historical and legal framework of being partially human at best, and defied the weight of stereotypes from popular media. Roots is not a pretty picture of inheritance, but instead one that spoke to audiences the realities of enslavement, resilience, continuity and survival in a vivid, cinematic fashion, from a narrative with an origin in the spoken word. That challenge and denial of oral history as a legitimate basis of the experiences of people of color is slowly eroding…. Slowly.

There is an equivalence in the genealogical field that is beginning to be dismantled, an implicit claim whereby scholastic levels of genealogy equates to whiteness. Yet to paraphrase Audrey Lorde, one cannot dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools.[11] This work is done as the field opens up to POC more broadly, who bring a different set of experiences, lineages and techniques that draw upon contexts both within and outside of traditional genealogy.[12] It is also up to genealogists who are not POC to weigh what that legacy is and how it impacts the who, what and where of their practice.

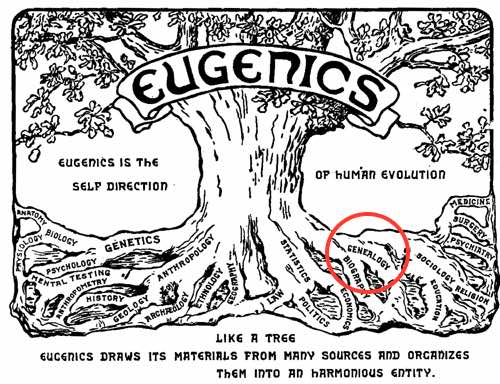

In order to see the connection between genealogy and the ideology of whiteness more clearly, one has to go back to the 1880s, when genealogy was part of the toolkit for the pseudoscience of eugenics. This was a conduit for previous ideas about racial inferiority from the previous century, now cloaked in respectable ‘science’. It was buttressed by social and institutional dynamics that maintain racial hierarchies and racialized public policies and institutional practices, a shifting framework that is still in operation today. [13] It is a discourse of social division and superiority emergent after the election of November 2016, thrown into relief by the events at Charlottesville, Virginia.

Eugenics: technologies of segregation, genealogy & policy

At its most basic, eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices about how to improve the human population. There was ‘positive eugenics’ aimed at promoting sexual reproduction among those with desired traits and ‘negative eugenics’, which sought to limit certain populations from reproducing. The movement started in the UK and spread to many countries, including the US and Canada in the early twentieth century. This instigated the formation of programs intent on improving the population, that led to marriage prohibition and forced sterilization programs.[14] These experiences are part of thousands of family histories tied to experimentation, social policies, with roots in settler colonialism.

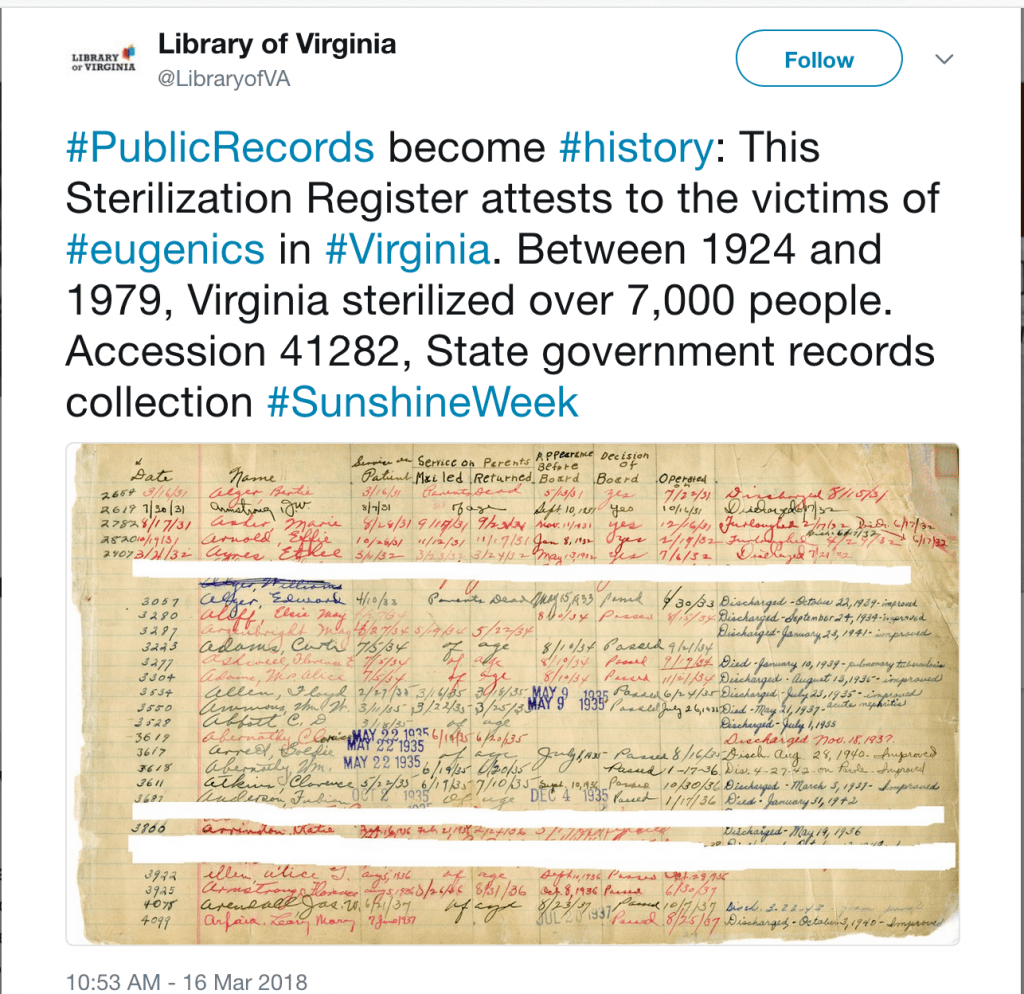

Genealogy was important to eugenicists, because it was a map that traced the transmission of ‘defective germ-plasm’ through families, which contrasted with the legacy of white western men with genealogies of ‘quality’. This ultimately translated into policies that generated thousands of sterilizations, destroyed families with the fear of miscegenation, and transformed poverty into a problem of the individual, not society. Yet many states passed laws, as did Virginia that led to over 7,000 people being sterilized– and increasingly as archives make these documents available to the public, a better understanding of the high cost of eugenic policy emerges. Many paid, and continue to pay with their lives.

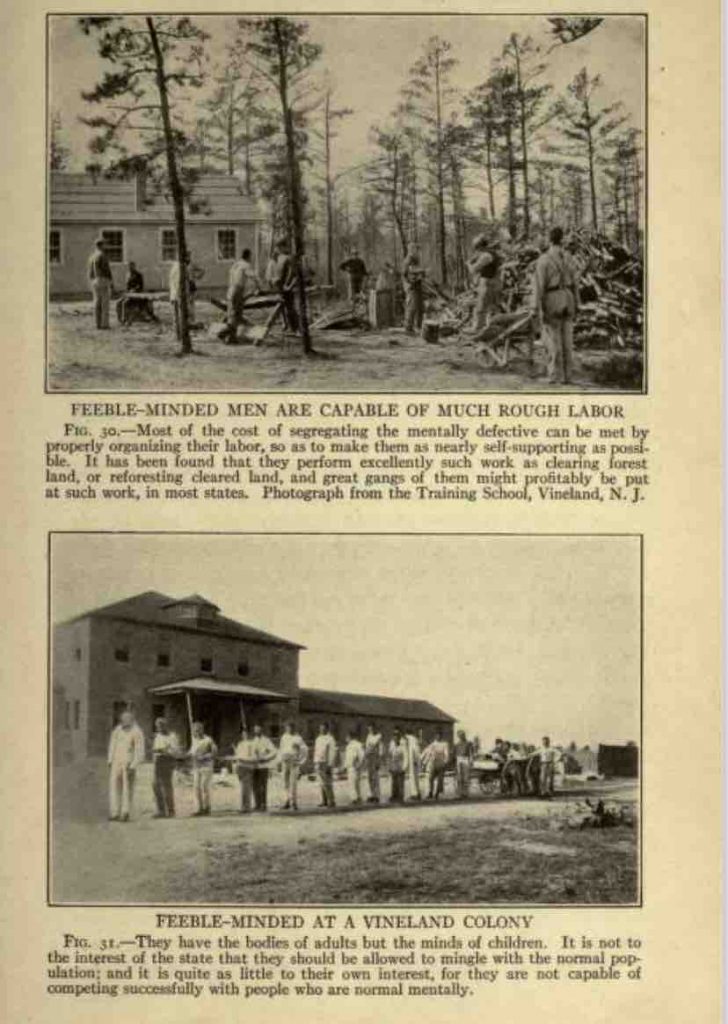

Paul Popenoe & Roswell Hill Johnson’s Applied Eugenics (Macmillan, 1918) is an appalling and unapologetically racist book. In it, the authors suggest that genealogy become the study of heredity and the legacy of traits in a family. It denies the backdrop of colonialism and slavery to blame peoples of African descent, immigrants and those living in poverty for the conditions that result from exploitation. Conveniently, context does not come into their analysis: “The historical, social, legal and other aspects of genealogy do not concern the present discussion. We shall discuss only the biological aspect…”[15] Genealogy was seen as the way to accomplish the goal of identifying certain lineages as social problems to be dealt with via policy decisions.

Consider the backdrop for the publication of this text- in 1915, Popenoe presented his paper on eugenics at the First International Congress of Genealogy, sponsored by the California Genealogical Society and held during the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. That same February that this world’s fair opened, also saw the release of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, 3 hours of racist propaganda that fired up the Lost Cause, the KKK and stoked racial violence. None of this is lost on myself as a colonial subject, a Taino woman of ethnic admixture with a disability, who was elected and happened to be the first POC to become President of the California Genealogical Society just a century later. I worked with the board to change our motto to “Connecting people to their diverse family heritage.” I imagine Mr. Popenoe is spinning in his grave.

Over three decades, eugenic explanations went over big in the US. The authors pointed to the centrality of genealogy in delivering eugenics as a means to controlling populations ‘scientifically’:

“The science of genealogy will not have full meaning and full value to those who pursue it, unless they bring themselves to look on men and women as organisms subject to the same laws of heredity and variation as other living things. Biologists were not long ago told that it was essential for them to learn to think like genealogists. For the purpose of eugenics, neither science is complete without the other; and we believe that it is not invidious to say that biologists have been quicker to realize this than have genealogists. The Golden Age of genealogy is yet to come.” [16]

Medicine, law, sociology and statistics were seen as the beneficiaries of genealogical information collected at centers in the US. This led to some 60,000 Americans being sterilized in the US between 1907 and the 1970s. [17]

Popenoe’s book offers justifications for segregation, and falls back on phrenology’s racial hierarchies for explanations of inferiority as intrinsic to the body. In terms of the black body, the book conflates the limitations of resources with a lack of progress, noting that “If so, it must be admitted that the Negro is different from the white, but that he is eugenically inferior to the white.”[285]

Those who did better on the tests were surmised to have “more white blood in them” and proceeds to determine a racial quantum based on percentages as did Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), and the eighteenth century Casta paintings of Mexico. [288]. You can revisit some of Jefferson’s ideas about African peoples excerpted here .

It follows that Papenoe and Hill Johnson proposed to prohibit interracial marriage, and their chapter on ‘The Color Line’ culminates with recommendations to put this into law as four states did (LA, NV, SD, AL) by 1918, before turning to immigration. [296]

Across the text, begins to appear the familiar language that Nazi Germany put into operation— the idea that the colonizers of North America were of the Nordic race appears on p 301, and proposals for implementing sterilization to stop those ‘whose offspring would probably be a detriment to race progress.” [185] The plan is to remove people to a colony, tracts of land with large buildings to separate out the unwanted [189] [17]

The idea of separation and segregation was one endorsed by law across the US and funded by various non-profits that discovered ways to ‘elevate’ those with ‘Nordic’ ancestry, while subjecting the poor, infirm, immigrants and people of color to identities and practices such as sterilization that reinforced their subjugation. As historian Edwin Black noted, “California was the epicenter of the eugenics movement” that had “extensive financing by corporate philanthropies, specifically the Carnegie Institution, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Harriman railroad fortune. They were all in league with the some of America’s most respected scientists hailing from such prestigious universities as Stanford, Yale, Harvard and Princeton.”

Charities were paid to seek out immigrants in “crowded cities and subject them to deportation, trumped up confinement or forced sterilization.” The Rockefeller Foundation even funded a program that Josef Mengele worked in before he went on to Auschwitz. It comes as no surprise then, that such organizations propagandized for the Nazis, and funded them in Germany. If one fell beyond the gentrified genetic lines such as those persons who worked, researched and enabled the legal structures of these programs, those deemed weak or unfit were subject to extraction.

In August 1934, California eugenicists arranged for a Nazi scientific exhibit to be shown at the LA County Museum as part of the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association.[18] Such exhibits legitimized what circulated in American popular culture through the 1920s and 1930s at state fairs and even world fairs.[19] Similar ideas are circulating today within Far Right channels and from members of the US Government today; internationally, we see the growth of this ideology spread within sites of settler colonialism.

Eugenics hit its nadir within a decade through its association with Nazi Germany, and later testimony at the Nuremberg trials, where human rights abuses carried out as eugenics programs were claimed to be little different than the US. [20] What is problematic is that wherever such programs are employed, the criteria of selection are determined by whatever group is in political power. [21]

It is precisely this history that the field of genealogy has to recover from.

Conclusion

As a field, genealogical practice has expanded beyond the accumulation of facts and details to encompass the social histories of those overlooked or at risk of falling into obscurity. Cemeteries are being restored and along with that, the local histories of suppressed, exiled or earlier occupants of towns and cities are coming into visibility- and let us include and embrace our diasporic connections and activities within this circle.

Documentaries, podcast series like those of Angela Walton-Raji’s African Roots podcast and Bernice Bennett’s Research at the National Archives and Beyond help to disseminate new information, findings and work through social media channels. These sources have reached audiences well beyond the journal publications of various genealogical and historical societies.

There is an opening up towards acknowledgement of past harms done to various communities, that acknowledge pain while transforming it into knowledge and sites where people can come to the table and support each other in unpacking the past. This is not a kumbaya moment, but one where the aftermath of enslavement and its social and institutional reach into the present can be faced.

DNA adds another dimension, revealing past relationships that range from the coercive to the consensual that happened, and when augmented by oral history and documents, the process literally brings into visibility parts of ourselves through enslaved ancestors, free and freed people and slave holders. There are many of us who seek the receipts that establish this more contentious family history, fraught with scars and triumphs, that confirms and grounds a movement toward freedom and self determination.

The fears of the last century about the reach of one book that captured the imagination of millions as a faulty model for genealogical research were ultimately unfounded. After Haley’s book was published and the program series Roots aired, “letters of inquiry and applications to use the National Archives rose 40%.[22] General interest in genealogy continues, as it offers a path to situate personal history in the larger context of national history, and to continuing education.

Recently, course offerings for genealogists are focused on writing family histories, and now, genealogical societies are taking it one step further and offering seminars on writing historical fiction based on family history. What the Abolitionist movement of the nineteenth century knew was that an audience had to hear not just facts, but a narrative, conveyed by a powerful voice or on the page, and if possible, to offer visual proof through photographs— all media used to convey their urgent message.

Ultimately, our task is to make visible and thereby end the historical erasure of difference (ethnic, race, gender, class) in the historical and genealogical record, and thereby honor those who came before us, our ancestors and their struggles.

References

1. BlackProGen LIVE, 11 October 2016. Ep.20b Talks Diversity in Genealogy and Family HIstory. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G1Z7Anc4Fj8&t=2s

2. Nicka Smith, “The Problem of the Color Line”, Who is Nicka Smith?.com http://www.whoisnickasmith.com/genealogy/the-problem-of-the-color-line/

3. Elizabeth Shown Mills and Gary B. Mills. “The Genealogist’s Assessment of Alex Haley’s Roots.” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 72 (March 1984): 35–49. 35-36. Digital image. Elizabeth Shown Mills, Historic Pathways. http://www.HistoricPathways.com : [9 Oct 2016].

4. “Although some Americans have been conditioned to superimpose racial divisions upon almost all aspects of life, such academic distinctions cannot exist in the science of genealogy.

It is true, at the same time, that certain procedures in the pursuit of black genealogy do differ from those in the pursuit of English genealogy, that the pursuit of ancestral research among white Creoles of Louisiana is different from that among the Pilgrims of Massachusetts, that research in Virginia differs from research in Tennessee, that research on black families in Alabama differs from that on black families in New York.” Elizabeth Shown Mills and Gary B. Mills. “The Genealogist’s Assessment of Alex Haley’s Roots.” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 72 (March 1984): 35–49. 35-36. Digital image. Elizabeth Shown Mills, Historic Pathways. http://www.HistoricPathways.com : [9 Oct 2016]

5. Gary B. and Elizabeth Shown Mills, “ROOTS and the New ‘Faction’ a Legitimate Tool for Clio?.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 89:1, Jan 1981, 4. Digital image. Elizabeth Shown Mills, Historic Pathways. http://www.HistoricPathways.com : 15 Oct 2016.

6. “The structural racism lens allows us to see more clearly how our nation’s core values— and the public policies and institutional practices that are built on them — perpetuate social stratifications and outcomes that all too often reflect racial group sorting rather than individual merit and effort. The structural racism lens allows us to see and understand: the racist legacy of our past; how racism persists in our national policies, institutional practices and cultural representations; how racism is transmitted and either amplified or mitigated through public, private and community institutions; how individuals internalize and respond to racist structures. The structural racism lens allows us to see that, as a society, we more or less take for granted a context of white leadership, dominance and privilege.” The Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change, Structural Racism and Community Building. June 2004, 12. https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/docs/rcc/aspen_structural_racism2.pdf Accessed 9 Oct 2016.

7. See the steps and bibliography for James Ison’s syllabus “Using the Genealogical Proof Standard for African American Research” presented at two national conferences in 2010 https://familysearch.org/wiki/en/Using_the_Genealogical_Proof_Standard_for_African_American_Research Accessed 15 Oct 2016

8. Edmund Morgan quoted in Israel Spencer, NYT, 10 Apr 1977; in Mills, “ROOTS and the New ‘Faction’, 4.

9. Alex Haley, quoted in Nancy Arnetz, “From His Story to Our Story: A Review of “Roots”. Journal of Negro Education, 46:3, Summer 1977, 367-372. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2966780, 367

10. Arnetz, “From His Story to Our Story: A Review of “Roots”. Journal of Negro Education, 367-372, 368.

11. “Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between and individual and her oppression. But community must not mean a shedding of our differences or the pathetic premise that these differences do not exist. Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucible of difference— those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older— know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only means of support.” Lorde’s title and her question remain pertinent: “What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?” It is important to note that this seminal essay was written in acknowledgement of the lack of participation of Third World women of color at NYU’s Institute for the Humanities Conference. Audry Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Ed. Berkeley Press, 1984. http://muhlenberg.edu/media/contentassets/pdf/campuslife/SDP%20Reading%20Lorde.pdf Accessed 16 Oct 2016.

12. Consider the development of networks of genealogical organizations AAHGS and institutes, such as MAAGI, the AAHGS’ Afrigeneas.org project, the explosion of genealogical groups on Facebook, and efforts such as the transcription of the Freedmen’s Bank papers on FamilySearch among many others that point to the blossoming of the field. There remains more to be done in terms of acceptance and incorporation of difference for genealogy by POC.

13. “Structural Racism Produces Racialized Outcomes.” See Chart, Structural Racism and Community Building. The Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change. June 2004, p12. https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/docs/rcc/aspen_structural_racism2.pdf

14. “Eugenics.” Wikipedia.org https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugenics Accessed 12 Oct 2016.

15. Paul Popenoe & Roswell Hill Johnson, Applied Eugenics (Macmillan, 1918) 339.

https://archive.org/details/appliedeugenics00popeuoft

16. Christina Kennedy, “Invisible History of the Human Race.” Huffington Post, 5 Jan 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/christine-kenneally/genealogy-eugenics_b_6367344.html? Accessed 11 Oct 2016.

17. Popenoe & Hill Johnson, Applied Eugenics.

18. Edwin Black, “The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics.” History News Network, Sept, 2003. http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/1796 Accessed 12 Oct 2016.

19. Steve Selden, University of Maryland. Eugenics Popularization. http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay_6_fs.html Accessed 12 Oct 2016.

20. Black, “The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics.”

21. “Eugenics.” Wikipedia.org

22. ERIC, “ERIC ED 462329: Discovering our Roots: Making History Meaningful. A Guide for Educators.” 2001. https://archive.org/details/ERIC_ED462329 Accessed 12 Oct 2016.

Resource List: Blogs

Check out the blogs of the professional genealogists and researchers on Black ProGen below:

Bernice Bennett: Research at the National Archives and Beyond http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bernicebennett

Linda Buggs-Sims: Mississippi Rooted http://www.mississippirooted.com/

Toni Carrier: Low Country Africana: African American Genealogy in SC, GA & FL http://www.lowcountryafricana.com/

Shannon Christmas: Through the Trees http://throughthetreesblog.tumblr.com/

Melvin J Collier: Roots Revealed: Viewing African American History Through a Genealogical Lens http://rootsrevealed.blogspot.com/

Vicki Davis-Mitchell: Mariah’s Zepher: An Ancestral Journey through the winds of time planting seeds in Harrison and Grimes County Texas http://mariahszepher.blogspot.com/

Ellen Fernandez-Sacco: Latino Genealogy and Beyond https://LatinoGenealogyandBeyond.com

Robin R. Foster: Saving Stories: People gathering around family history http://www.robinsavingstories.com

George Geder: Geder Writes http://www.gederwrites.com/

True Lewis: Notes to Myself http://mytrueroots.blogspot.com/

Dr. Shelley Murphy: Family Tree Girl https://familytreegirl.com/

Drusilla Pair: Find Your Folks: A Journal about Family and History http://findyourfolks.blogspot.com/

Renate Yarborough-Sanders: Into the the LIGHT http://justthinking130.blogspot.com/

Nicka Smith: Who is Nicka Smith? http://whoisnickasmith.com/

Michael J Twitty: Afroculinaria https://afroculinaria.com/

Teresa Vega: Radiant Roots, Boricua Branches http://radiantrootsboricuabranches.com/

Angela Walton-Raji: African Roots Podcast http://africanrootspodcast.com/

Monticello

Getting Word Project: https://www.monticello.org/getting-word

Coming Home with Slave Dwelling Project: https://www.monticello.org/site/blog-and-community/posts/coming-home-slave-dwelling-project