What are the origins of the Ubiles families of Barrio Mabu, Humacao? This post is part of a larger project that explores the lives of ancestors who lived centuries before in Northeast Puerto Rico. As a genealogist, this was an opportunity to delve into the ancestry of Marie Ubiles, and share more about what documents hold about her ancestors, Juan Lorenzo Ubides Rodriguez and Petrona de la Cruz Amaro. First I needed to explore who were among those who held the surname during the late seventeenth-early eighteenth century in Northwest Puerto Rico. Here is the first chapter of the project.

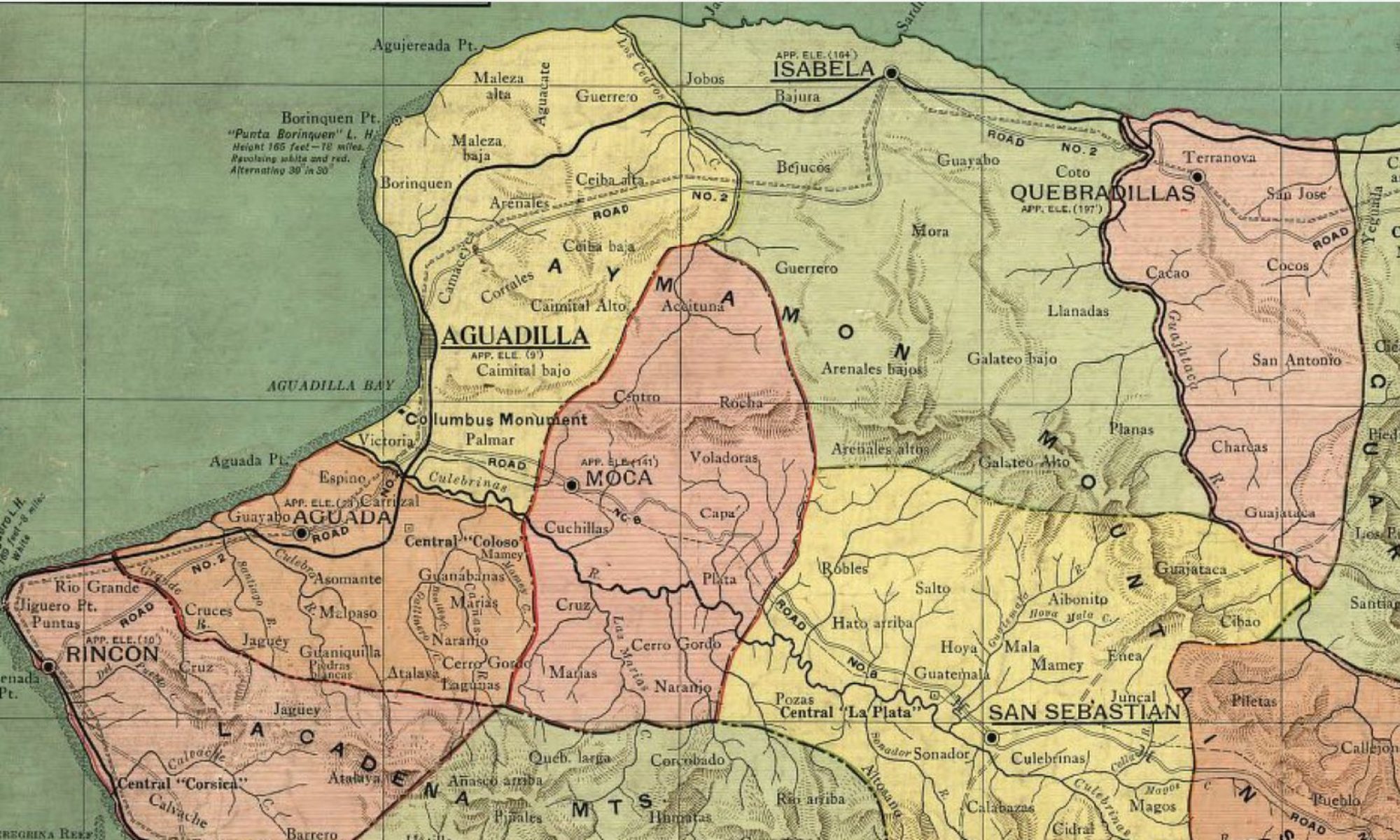

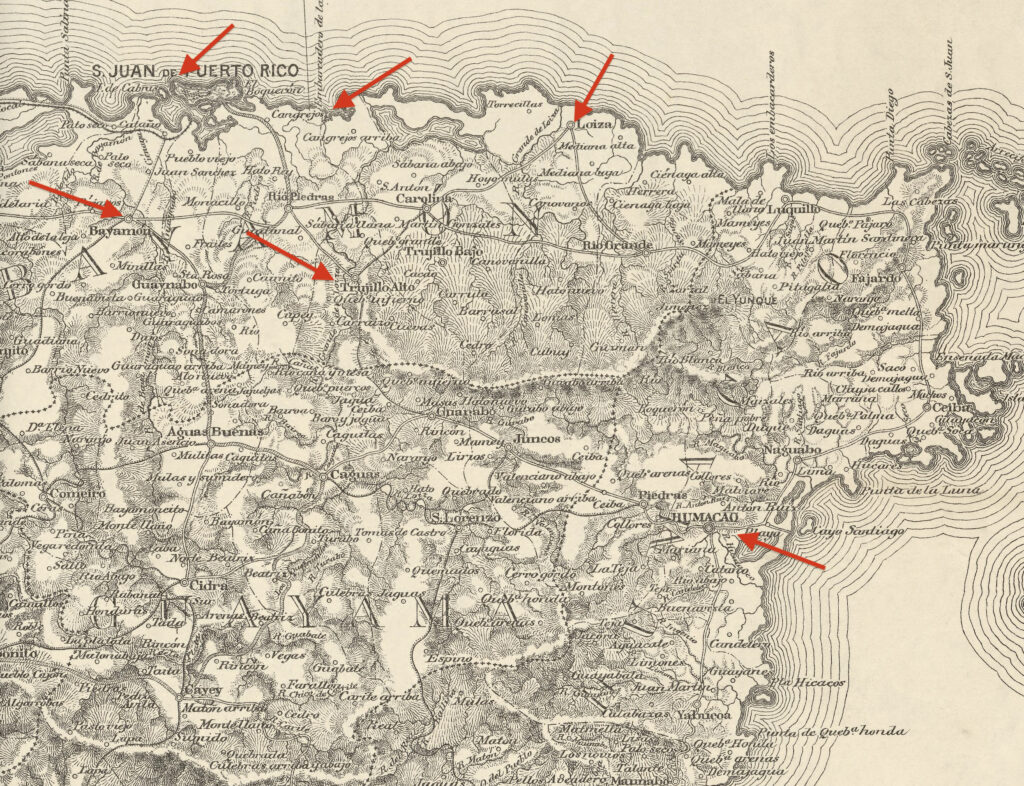

The locations for the Ubiles family clusters extend across the Northeast by the early eighteenth century.

Origins

In Puerto Rico, the surname Ubiles begins with Capt. Miguel Joseph de Ubides y Espinosa, born in 1699 in Puerto de Santa Maria, Cadiz. Son of Juan de Ubides and Ysabel Calderon, it is unclear as to whether his parents came to the island at all. Miguel de Ubides was once a partner and then an enemy of Capitan Miguel Enriquez, the privateer who rapidly ascended San Juan’s social caste, only to be turned upon later. Both Enriquez and Ubides’ were enslavers and slave traders, and here lies the origin of the Ubides of color. Over time, the spelling of those once enslaved changed.

Properties

Capt. Miguel de Ubides married Cecilia Sanchez Araujo on 8 July 1720 in the Cathedral de San Juan, and they had at least four children. One reached adulthood, Juan Manuel Ubides Araujo born in July 17341. Unlike many dwellers of the time in San Juan, Ubides lived in a two-story building. It was described by historian Angel Lopez Cantos, and based on a July 1725 inventory of de Ubides’ embargoed property:

Y la casa de fiel ejecutor del cabildo de San Juan, Miguel de Ubides, tambien era de dos plantas. En la anterior había una ‘sala’ que ocupaban mitad del espacio y la otra un ‘aposento’ y una ‘despensa’. Abajo solo había un habitación que servia de tienda y el postal. El hueco de la escalera lo habían tapiado y hacia las veces de ‘almacén2’.

And the home of the faithful executor of the cabildo of San Juan, Miguel de Ubides, was of two floors. In the rear was a large hall that took up half the space, another chamber and a pantry. Below there was a bedroom that served as a store and the post office. The space underneath the stairs was closed off and at times, served as a warehouse.

This lends an idea of the kinds of property and labor that de Ubides used in his business—there would be a need for domestics, cooks, storekeeper, clerk, and porters, all roles that could be done with enslaved workers. This knowledge also represented a route to freedom in early San Juan, if one were able to arrange buying it. To know these aspects of how to run a business oneself meant one could openly support their own families once out of bondage.

Smuggling

The sixteenth – seventeenth centuries were a time of smuggling in the Caribbean, as Spain paid more attention to the development of silver mining in the Yucatan and its other colonies. As a result, Puerto Rico was a hotbed of smuggling activity that connected merchants to Curacao, Venezuela and other islands . The ships and cargoes taken as prizes by Spanish and Spanish American merchants were sold in the British West Indies. [See Cromwell 2018]

Miguel de Ubides was involved with Captain Miguel Enriquez, the privateer hired by the Spanish government. Eventually, Enriquez was turned against by the elite of San Juan, disturbed by his rapid social climb and business expansion. Another reason they resented him was that Enriquez was the grandchild of an enslaved woman from Angola, and in a world where the proximity to Europe was paramount, he did not fit in. de Ubides was among those who pitted themselves against Enriquez, and he also suffered the embargo of his property not long after. The larger question is how much of their business was involved with the slave trade. Lopez Cantos suggests that Enriquez’ holdings numbered over 200, including those enslaved who worked plantations. There is only a trace of people held by de Ubides and Enriquez in surviving parish records.

Enslaved Persons Held by Miguel de Ubides

The earliest mention of enslaved Ubides is in the pages of the extant books for Nuestra Senora de los Remedios in Viejo San Juan.

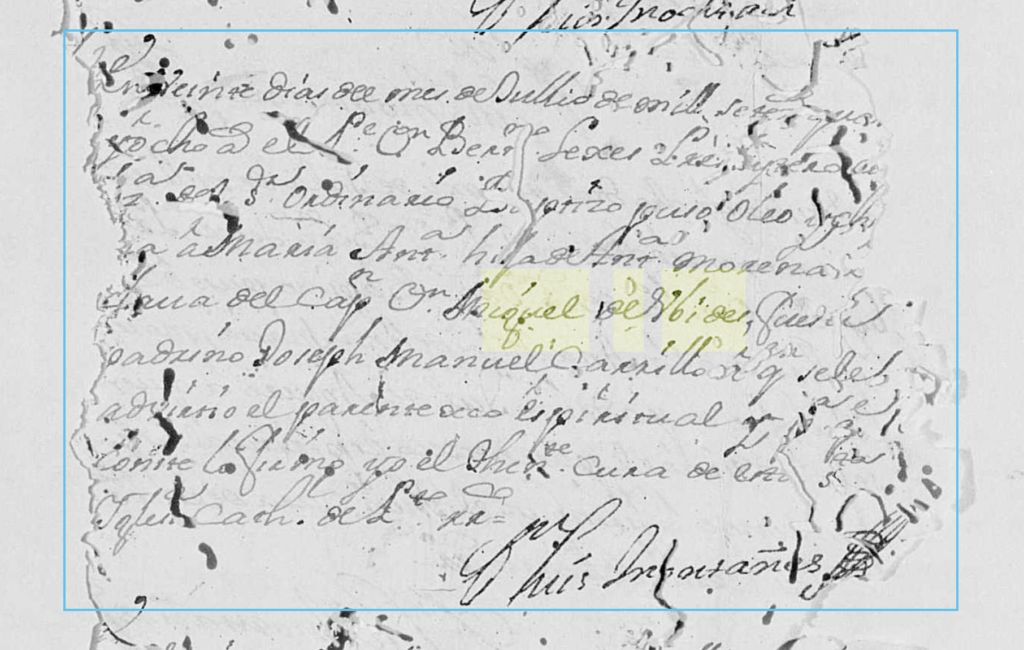

This July 1748 baptism for “Maria Antonia, hija de Antonia, morena esclava de Dn. Miguel de Ubides. Padrino, Joseph Manuel Carrillo3” is among the few documents for the enslaved persons held by Ubides. Antonia’s age is not noted, and she may be anywhere between 12 to 45 years of age, probably born in Puerto Rico.

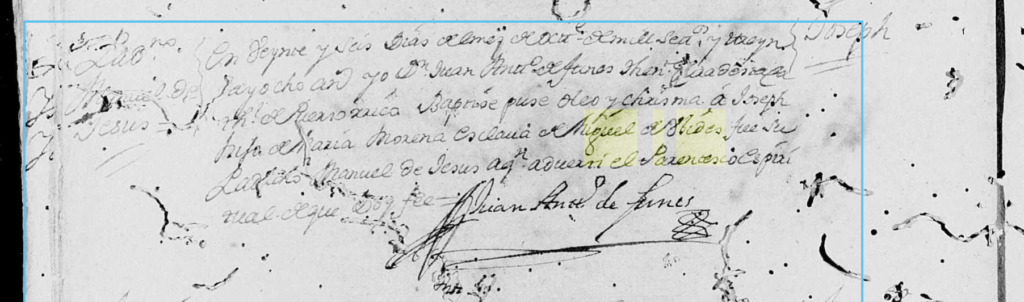

Maria, a Black woman enslaved by Miguel de Ubides in 1738 gave birth to Joseph, who was baptized on 26 October 1738, and Manuel de Jesus served as his godparent. This entry illustrates how ‘new property’ was registered through parish records. Additional documentation for Maria and Joseph may no longer be extant.

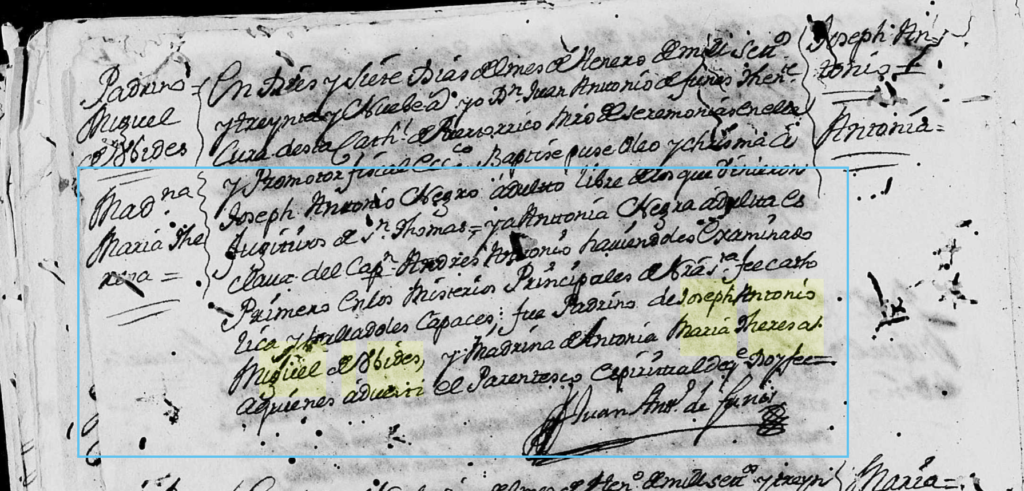

When Joseph Antonio, a formerly enslaved man from St Thomas was baptized on 17 January 1739, Dn. Miguel de Ubides served as his godfather5. Joseph Antonio, a freedman, was baptized together with Antonia, an enslaved woman held by Capitan Andres Antonio. Joseph Antonio’s conversion to Catholicism was an assurance to the Spanish crown of his loyalty [6]. What is unusual in this record is that two men brought two persons to be baptized, one who liberated himself from a British colony and the other, an enslaved woman. Why the double baptism? Were they a couple? There is no additional information to go on. Apparently, Joseph Antonio took the surname of his padrino after 1739- and is the same Joseph Antonio Ubides who dies in May 1770, married to Ana Lerey.

Summary

Several people of African descent carried the de Ubides surname in early-mid eighteenth century San Juan. As documentation is scarce, there is evidence of them in parish records. There are several clusters of this surname with a connection by name or association.

How many enslaved persons were held by Capt. Miguel de Ubides is unknown. Given that his property (like Enriquez) was impounded, an inventory was made of his holdings. It is possible that enslaved people appear on these pages, either as a numeric count, or perhaps, a named list. Protocolos from this time period for San Juan are unfortunately, not extant.

If you’re from one of the Ubiles family communities, I hope you’ll share your story.

References

- Juan Manuel Ubides, Acta Bautismo. “Puerto Rico, registros parroquiales, 1645-1969,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-KC9B-1?cc=1807092&wc=QZYD-N2K%3A149110901%2C149110902%2C149142201 : 14 December 2021), San Juan > Nuestra Señora de los Remedios > Bautismos 1723-1738 > image 147 of 216; paróquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Puerto Rico.

2. Angel Lopez Cantos, Miguel Enriquez. Ediciones Puerto, 3rd Ed, 2017, (1994) 96.

For an idea of the extent of smuggling, see Jesse Cromwell, The Smuggler’s World: Illicit Trade and Atlantic Communities in Eighteenth Century Venezuela. UNC Press, 2018.

3. Maria Antonia, hija de Antonia [Ubides] Acta Bautismo, “Puerto Rico, registros parroquiales, 1645-1969,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-K839-63?cc=1807092&wc=QZYD-2V5%3A149110901%2C149110902%2C149154801 : 23 December 2021), San Juan > Nuestra Señora de los Remedios > Bautismos 1747-1754 > image 33 of 220; paróquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Puerto Rico.

4. Joseph hijo de Maria [Ubides] Acta Bautismo, ‘Puerto Rico, registros parroquiales, 1645-1969,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9398-K833-2J?cc=1807092&wc=QZYD-2KM%3A149110901%2C149110902%2C149146801 : 15 December 2021), San Juan > Nuestra Señora de los Remedios > Bautismos 1735-1739 > image 114 of 143; paróquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Puerto Rico.

5. Joseph Antonio, Acta de Bautismo 1739″Puerto Rico, registros parroquiales, 1645-1969″, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6DBL-YF8Z : 15 December 2021), Joseph Antonio Miguel de Ubides in entry for MM9.1.1/6DBL-YF8C:, 1739.

6. Did Joseph Antonio Ubides serve in the military, as many free Black men did in Cangrejos? See: David M Stark, “Rescued from their Invisibility: The Afro-Puerto Ricans of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century San Mateo de Cangrejos, Puerto Rico.” The Americas 63:4 (Apr 2007), 551-586.