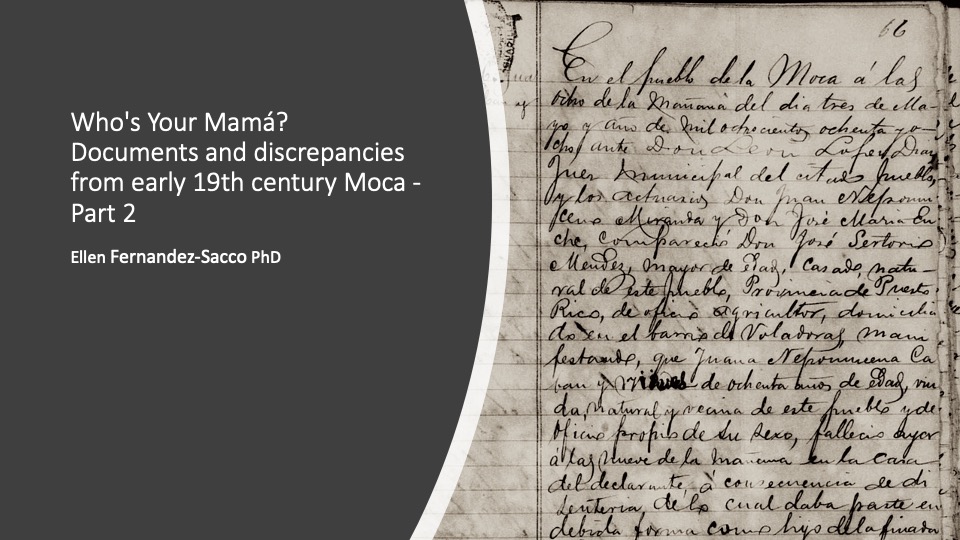

Part 3: Gathering Information & Pulling it all together

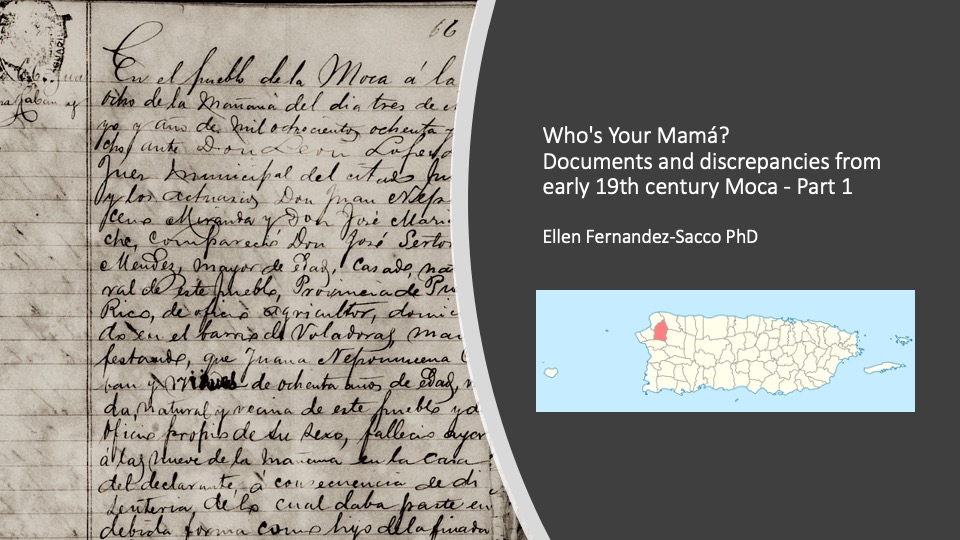

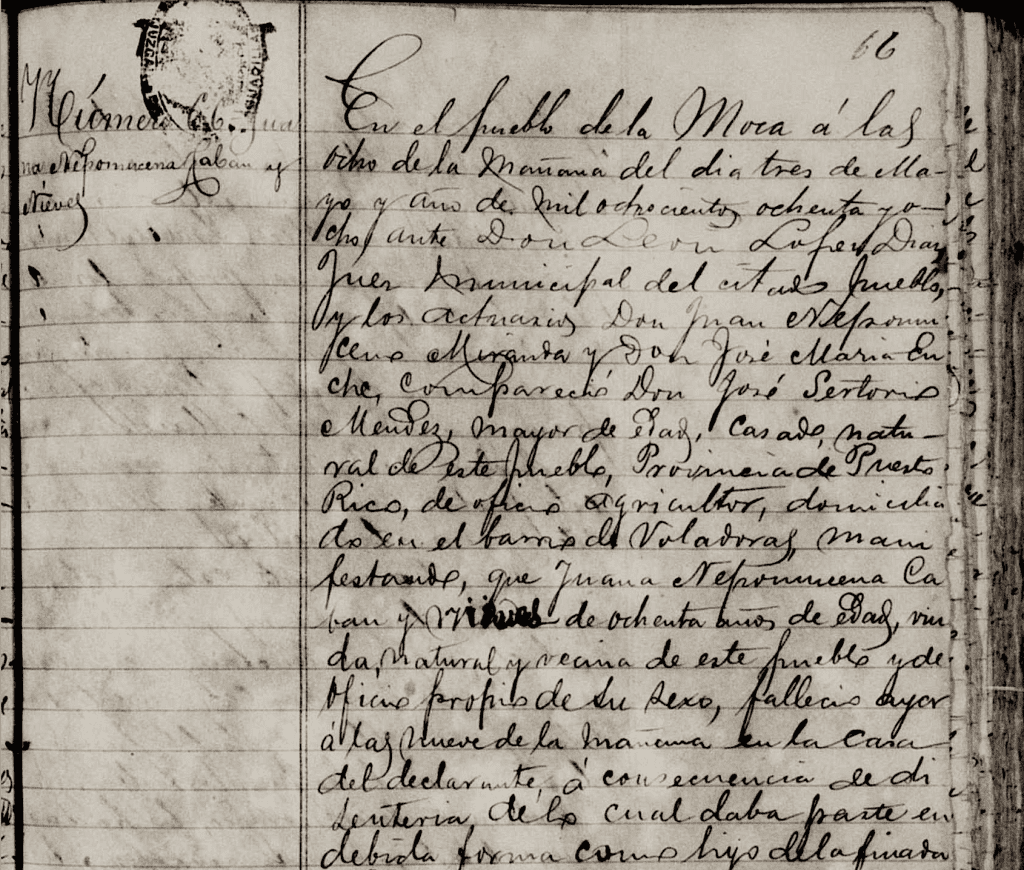

Gathering Data: What the Acta de Defuncion tells us

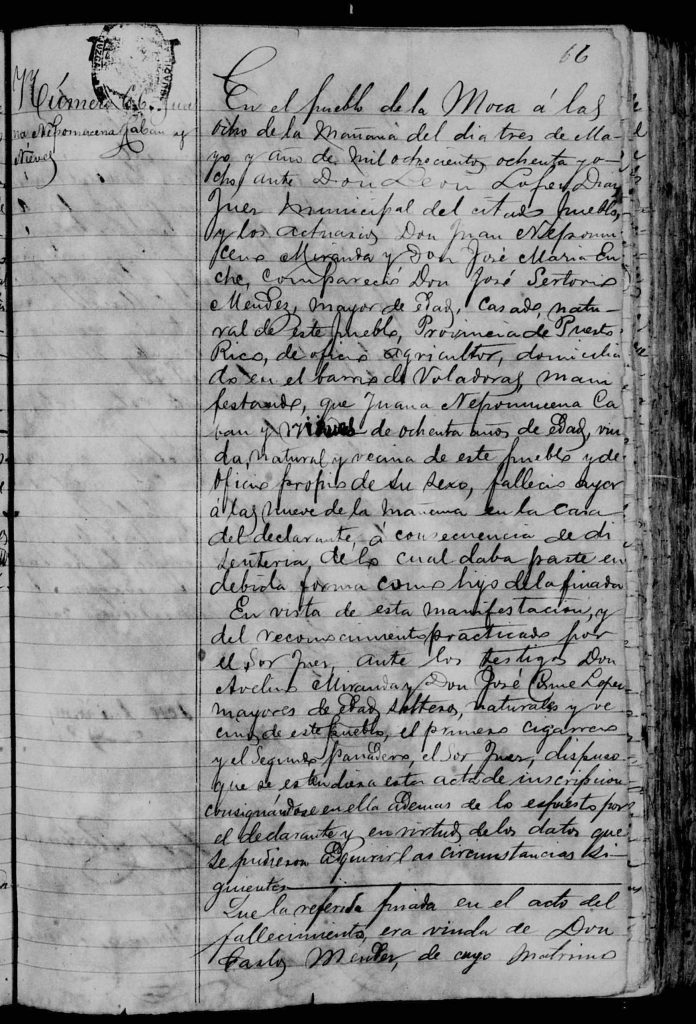

Four key facts can be gleaned from Juana Nepomucena Caban’s 1888 death certificate:

- Juana Nepomucena Caban was of advanced age

- Juana was widowed

- she had 14 children with Carlos Mendez… and,

- Carlos’ death preceded hers.

As Carlos Mendez is not in the Libro de defunciones, Registro Civil (Book of Deaths, Civil Register) for Moca or nearby municipalities, he probably died before 1885, the year this record set begins.

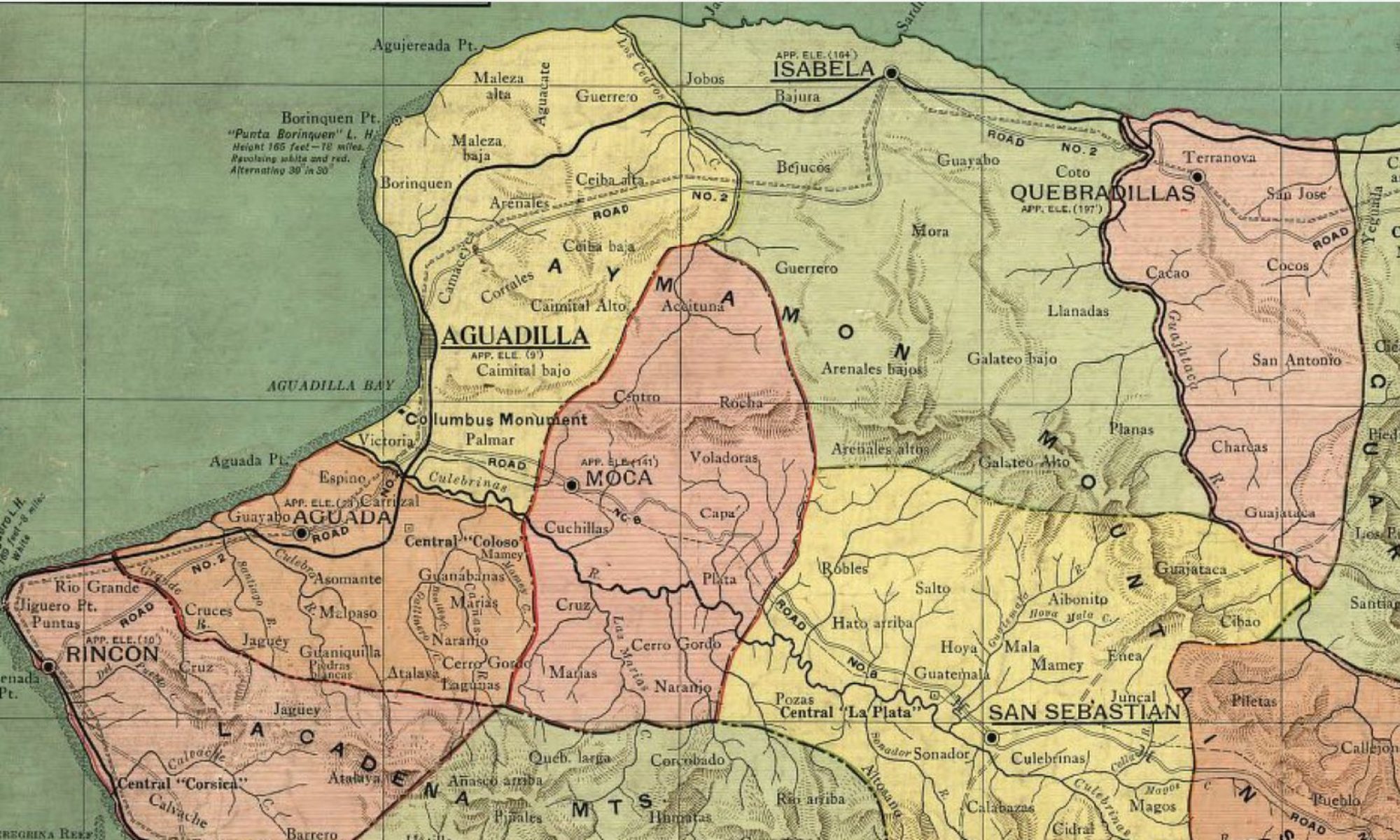

However, Carlos Mendez appears in land rentals and deeds for 1851 in notary documents. In Caja 1444 for Moca, he is mentioned as a neighbor in Barrio Cruz in two documents. Still, this bit of information helps place the family in a specific barrio (ward), adds a date, and can help in finding additional documents.

Steps

- First, review the document in question– what information is there?

- What questions do you seek to answer? What’s your research question?

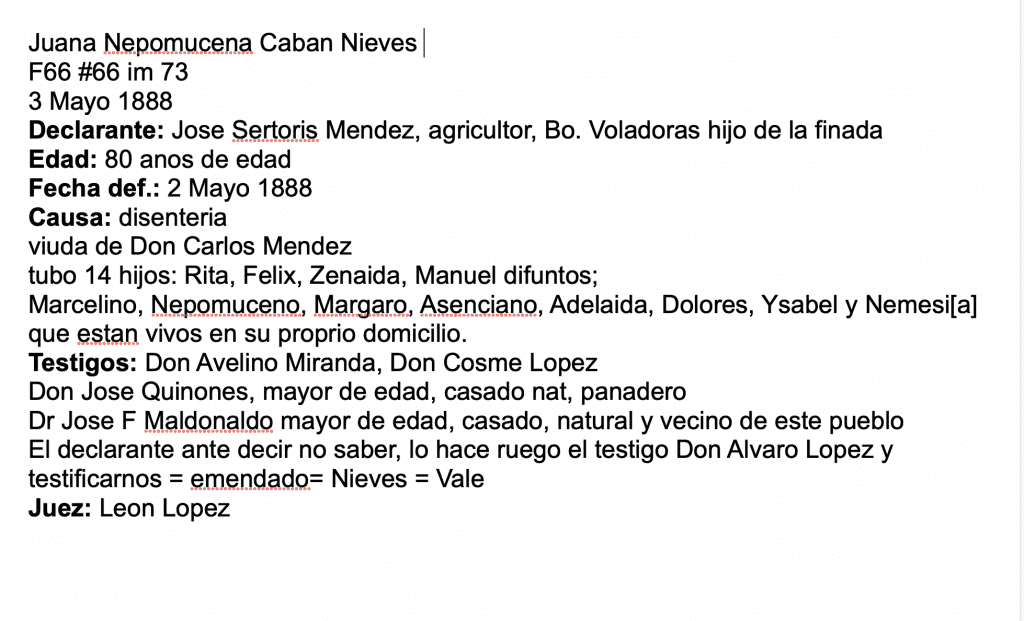

- Create a detailed extract, so you can focus in on the relevant details.

Make Your Own Extracts & Transcriptions

Given the handwriting across the documents in the Civil Registers, it’s often easier to refer to an extract than reread a document with difficult handwriting, so…

- A good extract contains more than just a name and a date.

- The informant (Declarante or Informante) is identified. This could be anyone from a relative, neighbor, doctor or local official, etc. depending on the circumstances.

- Witnesses (Testigos) may or may not be relatives. Sometimes they were locals entrusted with signing off on documents and not related to the persons listed.

- The informant’s identity can be a clue as to how reliable the information in the certificate is. Depending on the years, a birth, marriage or death record can provide the names of additional family members, neighbors or officials involved in the reporting of the event.

- Officials- Before 1910, Juez de Paz (Justice of the Peace) Secretario or Encargados del Registro Civil (Secretary or Clerk of the Civil Register) appear at the start and end of documents.

Knowing who was the official can provide context. This might be connected to the family in some way, particularly if we are studying rural areas. The further back in time, the more likely this is the situation.

Additional observations:

- Note any discrepancy between the date of the document registration and the date of the event. This can make quite a bit of difference in birth registrations- some people finally had their birth registered as adults. In terms of death records, the deceased is often buried the following day. It is unusual for the remains to be kept beyond 2-3 days prior to interment.

- In early church records, the cemetery surrounded the church building, and municipal cemeteries come later. Later in the nineteenth century, cemeteries were moved out of the town centers, and established further away as a better understanding of illness and germs take hold and public health becomes a field of study. For Moca, the church was built in 1853, and the cemetery located a few blocks away. The old cemetery was moved about 1953.

- Source the document, so you can locate the original (or its duplicate) in future. If it’s on FamilySearch, copy the Citation and paste it into your notes or genealogy program.

- Reexamine the original document periodically– errors can enter when transcribing. You may find there’s a significant detail missed on the initial reading.

- If you have access to original documents, learn to do your own transcribing and tackle that document. Just because a person is on someone’s tree, or it’s a database search result doesn’t mean it’s correct. Age, gender even surnames may be incorrectly noted.

- Cause of death may point to health issues that run in a family, or mention of accidents, instances of deliberate harm, etc.

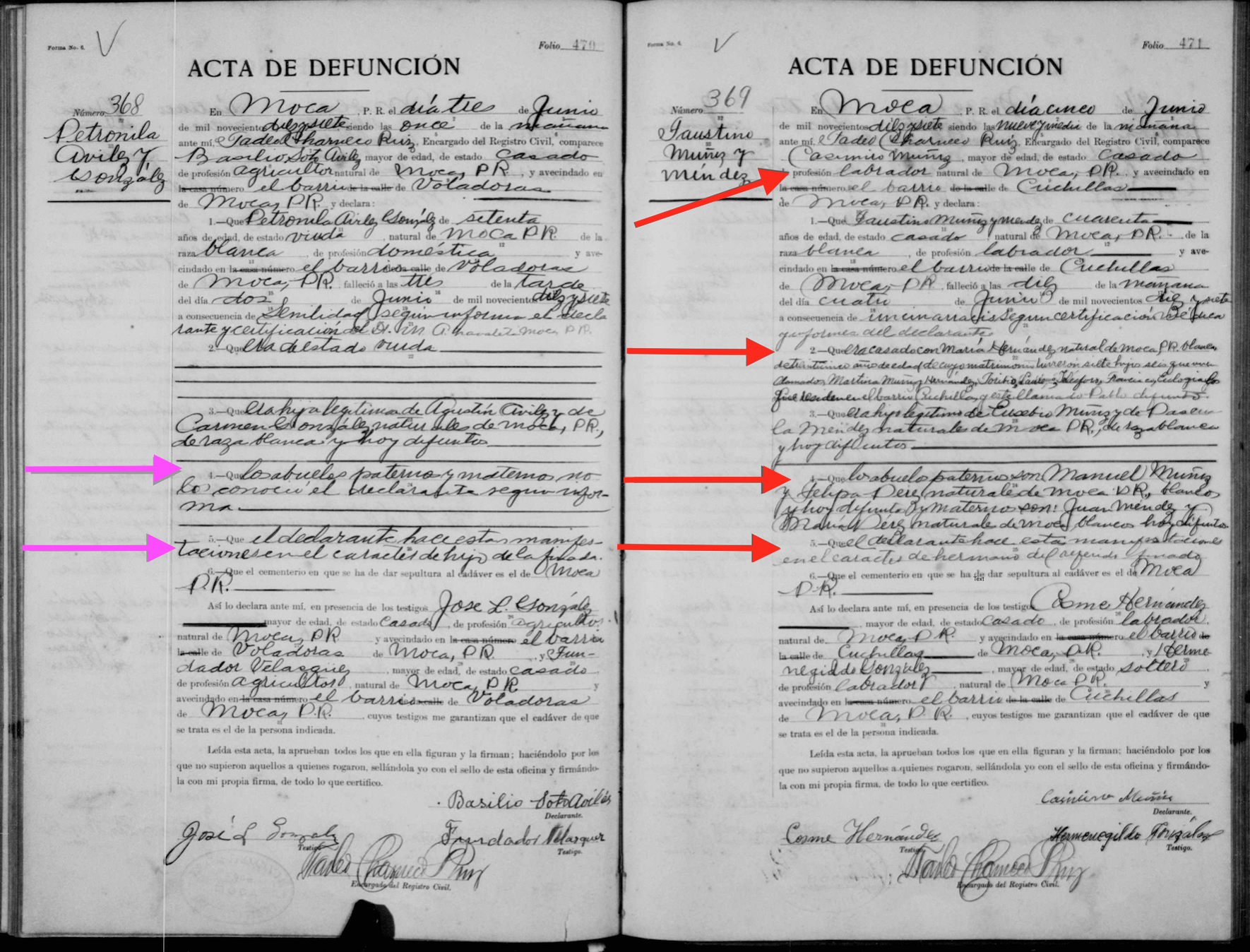

- Older documents may list paternal and maternal grandparents in series of birth and death registrations.

Here’s my extract, in Spanish.

This level of detail is helpful when you’re researching a brick wall, and notice most of this information doesn’t come up at all on the FS transcription, so definitely check out the document whenever possible.

Juana Nepomucena Caban [Nieves’] death certificate is available on FamilySearch ( & on Ancestry):

https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1-10454-2369-99?cc=1682798&wc=9376675

Information is knowledge: Reviewing what you’ve got

So, here is someone born near the start of the 1800s, a widow, identified as ‘white’, who had 14 children, ten of whom were still alive in 1888. We also have the name of her husband and the ward she died in.

Her son Jose Sertoris Mendez was the informant, and she was a widow. Note whether there is mention of a will— here, it’s not even mentioned.

Note that in this case, her son Jose Sertoris Mendez, like the majority of people who lived before 1900 in Puerto Rico, did not know how to write, and so, don Alvaro Lopez, signed on his behalf. This too has implications for records.

Who are Juana Nepomucena Caban’s Parents?

Yet, there’s an issue here— Juana Nepomucena Caban’s parents do not appear on the death certificate, which helps to confirm whether she actually is a Caban Nieves. Since she died a widow in 1888, both her death and that of her husband Carlos Mendez predates the first US Federal Census of 1910. As a search of the Civil Registration and the Index up to 1888 didn’t yield her husband, so he probably died before 1885.

What kind of documents are available? There are parish records, municipal documents and newspapers. If possible, secure a parish record from the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Monserrate in Moca. Check other trees, as there’s a chance another descendant may have already obtained one (hopefully with citations).

In this case, my cousin, Rosalma Mendez shared a set of extracts from the baptismal records that helped to fill in details that I’ve kept together with other early records. Working collaboratively, she is also a member of Sociedad Ancestros Mocanos. Before 2008, members of the group made transcriptions during appointments at the office of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Monserrate that we shared with each other. These lists can still contain surprises years later.

Estimating Timelines

Together with the birth year of the youngest child, a date range for Carlos’ death record can be figured out, and also a range for Juana’s childbearing years. Death records in Puerto Rico often have ages that are rounded up, and a largely rural existence paired with high rates of illiteracy meant many literally did not know when they were born.

Remember, since the person reporting is not the person named in the document (it’s a death certificate, right?), there can be errors in the information provided.

Ok, so let’s see what we can find out from records for her immediate family.

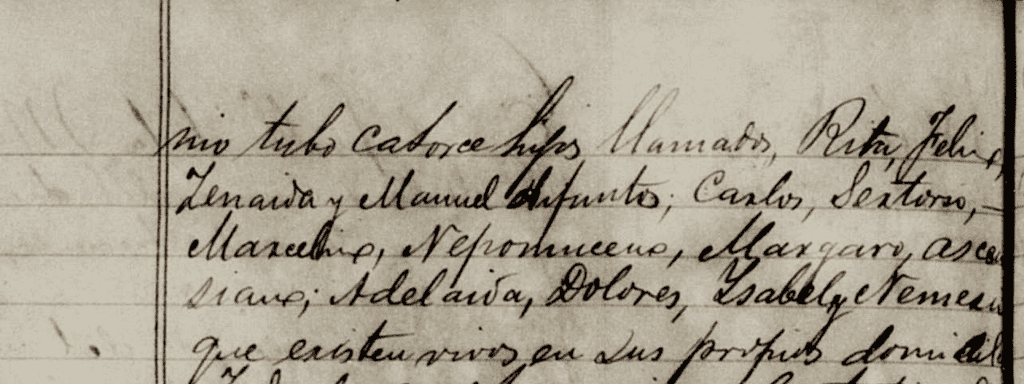

According to this Acta de Defuncion, Juana Nepomucena Caban and Don Carlos Mendez’ 14 children in the death record were:

Rita, Felix, Zenaida, Manuel deceased; Carlos, Sertoris, Marcelino, Nepomuceno, Margaro, Asenciano, Adelaida, Dolores, Ysabel y Nemesi[a] Mendez Caban.

Thanks to two additional records for Gregorio and Ermenegilda Mendez Caban, the couple’s total so far is actually 16 children. If a child died young, they may not be included among those listed in the parent’s death record, their Actas de Defuncion.

I used FamilySearch.org to locate a number of the records for the children, as these results can be more easily searched than in Ancestry.com‘s Puerto Rico Civil Registration record searches. On the other hand, both sites have family trees, and the large database that Ancestry has may turn something up, so it’s worth checking whether there are sources on the tree.

More questions… questioning death records

When I added the children’s information, I found was that their actual dates are much later than anticipated. This puts in question the 1808 year of birth from Juana Nepomucena’s age on the death certificate as eighty.

According to records, her births happened between 1832-1865. Children who died at young age are often left off the death certificates of their parents decades later, so it’s good to search the surname to find anyone else. Transcriptions for her children’s baptisms added very helpful details.

Ultimately, it turns out Juana’s age in the death record is incorrect, as her last child, (unmentioned among the children in her death record), is Ermenegilda Mendez Caban, born about 1865. Given Ermenegilda’s year of birth, if we use Juana Nepomucena Caban’s 1808 date means Juana was about 57, which is a little beyond childbearing years. The children’s years of birth range from 1832-1865, with a young mother born at ca. 1815- 1820.

How does that extra aging happen? Ages in death certificates are often rounded up, so a person can have an additional 5 to 10 years or more added on to get closer to 80, 90 or 100 years of age. Add the notation that records someone signed on behalf of the informant, is another clue that age can be a relative thing in these documents. The focus in daily life then was not so much on holding written documentation, but was dominated by the rhythm of the agricultural cycle. Much of the population during the nineteenth century was illiterate. Also, there were centenarians— but their records have more consistency in terms of age across time.

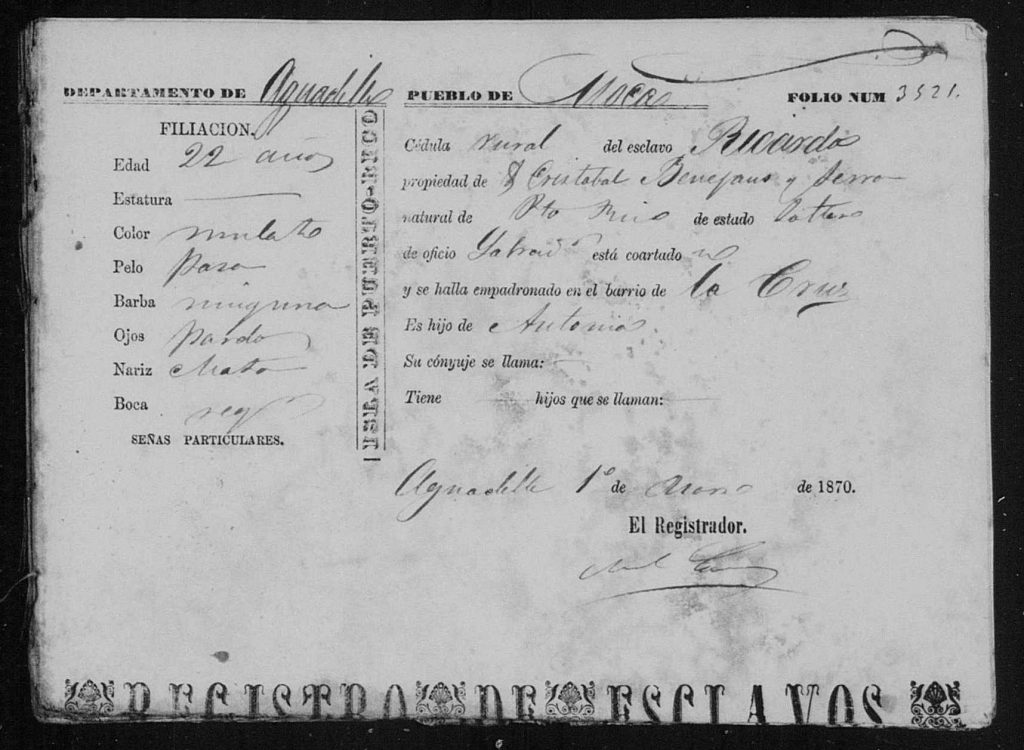

A maternal surname still missing…

We still need a record that will estabish Juana’s maternal surname, a big help when one is dealing with multiple families that share the same surname and a popular first name. Unfortunately, the records in the Civil Registers can fail to mention a maternal surname, or lack the name of a spouse or of parents. Depending on the time period, they can provide the names of parents and even grandparents. Having a single surname can be a clue to ethnicity and social status— POC in the earlier run of the Civil Register often appear with a single surname, for different reasons, because of former enslavement or birth to a single mother, or even father.

Thanks to Rosalma, the cousin who shared those transcriptions of baptism records for two of Juana and Carlos’s children- Gregorio and Maria Cenaida (Zenaida) Mendez Caban — we now see conflicting surnames for their maternal grandparents. For Gregorio, the maternal grandparents are Juan Caban and Juana Hernandez, and for Maria Cenaida, they are Juan Caban and Juana Lopez.[1]

Whenever possible, check the original and cross reference to determine whether the error was made in transcription or by the recording secretary or, the informant.

As there are no documents for Gregorio Mendez Caban in the Civil Registration, he probably died at a tender age, and the baptismal record is likely all that’s available on him.

It’s also possible that Juana Nepomucena’s potential mother, Juana Hernandez, has both surnames in question as Juana Hernandez Lopez. Women in records prior to the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century— could appear under either their mother’s or father’s surname, emphasizing the maternal line, or out of paternal recognition later on.

Still, even with the conflicting information, we have the names of Juana Nepomucena Caban’s father and her mother’s first name: Juan Caban and Juana —. As of yet, there is no further information regarding a possible second marriage for Juana’s husband Carlos Mendez.

And here we are…

So, based on two baptismal records, Juana Nepomucena was not a Caban Nieves after all. There is a discrepancy, and whether she was a Caban Hernandez or a Caban Lopez still remains to be resolved. That’s ok.

And often, it can’t be done alone, and best done in community to share the bits that may hold the answer to the mystery. You don’t have to go it alone, so look for groups sharing information about a given geographic area or for Puerto Rican genealogy overall. Ask. Between the years 1850 and 1888, details can certainly change across documents, and that’s why we need to do exhaustive searches.

If you’re related, or have info on Carlos Mendez or Juana Nepomucena Caban, please share!

References

[1] APNSMM Bautismos, Libro 15 21/MAR/52 nació: 6/p pg. 15 v; Maria Cenaira HL Carlos Méndez y Juana Caban; Abuelos paternos: Federico [Francisco] Méndez y Rosa Hernández; Abuelos maternos: Juan y Juana López; Padrinos: Silverio Aviles y Maria Adelaida Méndez;

22/MAY/1859 nació 9/MAY días pg. 49v Gregorio HL: Carlos Méndez y Nepoconucema Caban. Abuelos Paternos: Francisco Méndez y Rosa Hernández; Abuelos Maternos: Juan Caban y Juana Hernandez Padrinos: Juan de la Cruz Hidalgo y Maria Adelaida Mendez Transcriptions courtesy of Rosalma Mendez, 2006.