“All that I know of my ancestors was told to me by my people.“

The words of William J. Edwards, educator and founder of the Snow Hill Normal and Industrial Institute in Wilcox Alabama, are from his autobiography, Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt (1919). The book both explains how he received knowledge of his ancestors, and shows what they, and by extension, the Varner and McDuffie families were up against in the nineteenth to twentieth century.

Born in 1869, Edwards was born on the cusp of Reconstruction, and his perspective is firmly turned towards a brighter future of uplift. Given the centrality of oral history to this experience, it is worth reading the opening pages of Chapter 1. Childhood Days, as the Varners and McDuffies shared a similar history:

All that I know of my ancestors was told to me by my people. I learned from my grandfather on my mother’s side that the family came to Alabama from South Carolina. He told me that his mother was owned by the Wrumphs who lived in South Carolina, but his father belonged to another family. For some cause, the Wrumphs decided to move from South Carolina to Alabama; this caused his mother and father to be separated, as his father remained in South Carolina. The new home was near the village of Snow Hill. This must have been in the Thirties when my grandfather was quite a little child. He had no hope of ever seeing his father again, but his father worked at nights and in that way earned enough money to purchase his freedom from his master. So after four or five years he succeeded in buying his own freedom from his master and started out for Alabama. When he arrived at Snow Hill, he found his family, and Mr. Wrumphs at once hired him as a driver. He remained with his family until his death, which occurred during the war. At his death one of his sons, George, was appointed to take his place as driver

As I now remember, my grandfather told me that his mother’s name was Phoebe and that she lived until the close of the war. My grandfather married a woman by the name of Rachael and she belonged to a family by the name of Sigh. His wife’s mother came directly from Africa and spoke the African language. It is said that when she became angry no one could understand what she said. Her owner allowed her to do much as she pleased.

My grandfather had ten children, my mother being the oldest girl. She married my father during the war and, as nearly as I can remember, he told me that it was in 1864. Three children were born to them and I was the youngest; there was a girl and another boy.

I know little of my father’s people, excepting that he repeatedly told me that they came from South Carolina. So it is, that while I can trace my ancestry back to my great-grandparents on my mother’s side, I can learn nothing beyond my grandparents on my father’s side. My grandfather was a local preacher and could read quite well. Just how he obtained this knowledge, I have never been able to learn. He had the confidence and respect of the best white and colored people in the community and sometimes he would journey eight or ten miles to preach. Many times at these meetings there were nearly as many whites as colored people in the audience. He was indeed a grand old man. His name was James and his father’s name was Michael. So after freedom he took the name of James Carmichael.

One of the saddest things about slavery was the separation of families. Very often I come across men who tell me that they were sold from Virginia, South Carolina or North Carolina, and that they had large families in those states. Since their emancipation, many of these have returned to their former states in search of their families, and while some have succeeded in finding them, there are those who have not been able to find any trace of their families and have come back again to die. [1]

Edward’s account traces the movement of families, their sale and separation across states, the role of faith that was a path for his grandfather becaming a preacher, those who heard the voice of his African great grandmother who spoke an African language and through these traces, he makes the outlines of his community visible. All of these details were handed down via oral history, and made a document through the pages of his 1919 book.

The photo of Uncle Charles Lee standing before his home, supported by two canes, begins to tell of the conditions that Edwards sought to address after attending Tuskeegee and returning to Snow Hill to establish the first institute for Black education in Wilcox. The powers that be had little interest in seeing those who labored in bondage literate, educated and successful. And when they did gain it, threats intensified.

Violence &The Social Landscape of Wilcox County

A barometer of the low regard that people of African descent were held in is evident in this article “Extension of Slavery” from the 1862 issue of The Southern Cultivator, originally published in the Wilmington Journal. It evinces a line of white supremacist readership stretching from the middle to southern states, and the intent to keep the enslaved as a permanent unfree eternally laboring underclass.

What is telling is the absence of a name for the author, which speaks to fears about the power and potential of those fighting for their freedom from bondage. It is also an example of a proto-eugenic logic of an inherent, biological inferiority circulated via print media by the descendants of enslavers and their cohorts that later blossomed in the early twentieth century as eugenics. This reductionism still circulates in the present, as we struggle with 21st century issues of prison abolition and the returning semblance of debt peonage.

In case you can’t read the image:

A correspondent of the Wilmington Journal makes the following prediction: “I am not a prophet, nor am I the son of a prophet, but I now predict that one of the consequences of this war will be, that in three years from the end thereof there will not be a free negro in America; that our institution of slavery will be established on a more firm basis than ever; that the Northern States Rights party will get into power as soon as the elections roll round; the abolitionists will be hunted down like mad dogs, and the whole civilized world will become satisfied the our slaves are in the very condition for which nature designed them. Mark the prediction.”

In 1860, Wilcox County held only 26 ‘free colored’ and 17,797 enslaved people, with 6,795 whites, proportions that cast light on the nature of social and political life before the Civil War. By 1870, the ‘colored’ population increased to 21,610, a 21% increase, yet the white population remained at 6.795. [2]

Benson Seller’s Slavery in Alabama (1950) while remaining the main study of enslavement in that state, never addresses the humanity or “soul value” of Blacks held in bondage. Instead, the emphasis reflects the concerns with production, so that there are entries such as the following regarding planter James Asbury Tait’s management of overseers and their counsel to them. Violence and terror are the means of control, yet the text is in denial; we know that details of mangled, murdered and lynched bodies are omitted from this volume, instead we hear about ‘efficiency’:

First glimpse: 1866 Alabama State Census of Colored People

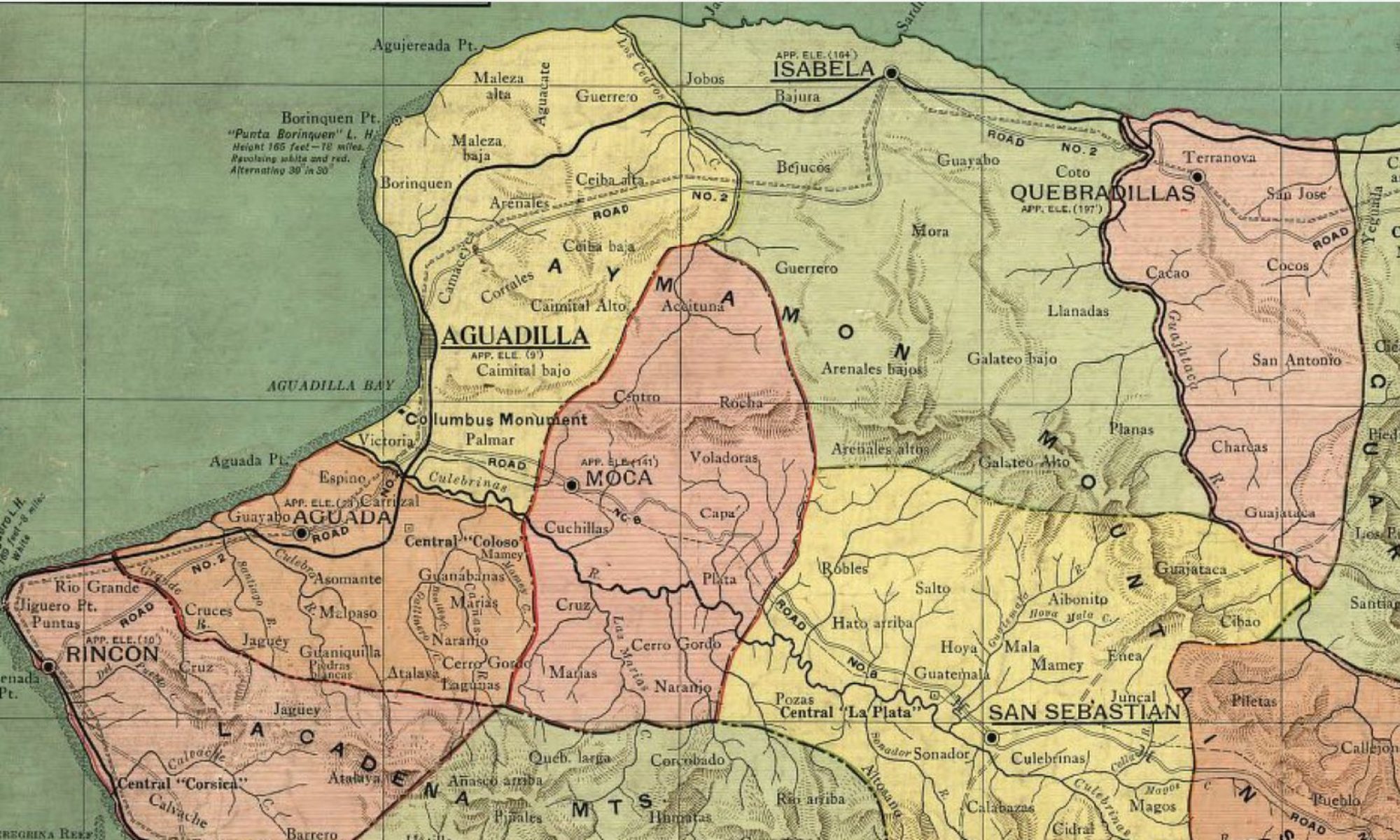

Only three generations back, the story of the Varner family that Della McDuffie Varner descends from has its first outlines in the documents issued during Reconstruction. On the Alabama Black Belt, Wilcox County borders Marengo County, and it is there in the 1866 Alabama State Colored Census for Marengo County that three Varners appear: King Varner, Matilde Varner, Haig Varner.

Making it official: Haig Varner & Fannie Varner

Haig Varner (b.ca 1820) and Fannie Varner (b.ca 1825) are Della Varner McDuffie’s great grandparents, the furthest back in the tree we can go at present. What we can’t tell from the data in the 1866 AL state census is how close these Varner families lived, and whether they were family or kin, as this is not spelled out. What is evident is that one to three generations lived across these households, and as this remains stubbornly opaque when compared to later census, now further documentation is needed to flesh out the details as to where exactly they lived in Marengo, who they were enslaved by, and how long they were in Alabama. Information from later census can vary as to origins of parents noted across the Federal census.

The Civil War ended, and the passage of The Civil Rights Bill of 1866 and the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments offered up citizenship and the start of Reconstruction offered hope for change. Alabama Voter Registration records were created as a result of the Reconstruction Act passed on 23 March 1867. [3]

Just months later, as a free man, Haig Varner registered to vote in Marengo County in 1867, an arrangement made possible by the presence of Federal troops; King Varner also appears in Volume 13. Other Varners appear in another volume of Alabama voter registrations, with Henry Varner in Volume 11, Alfred Varner and Anthony Varner in Volume 7 .[4]

Beyond the census, the total search results yield 16 Varners in Marengo County Alabama for the 1866 AL Register of Voters on Ancestry.com. The results are actually 8, as the page was shot twice on the microfilm:

Haig and Fannie Varner’s son, Richard ‘Dick’ Varner (1847-1920) took the opportunity to officiate his marriage vows, and have them recognized by the state on 25 March 1867. That they could marry and have their union officially recognized was also made possible by the Federal, rather than state government.

The Will of Samuel Varner, Marengo County, 1848

The names of some of these head of households—, Matilda Varner, Benton Varner also appear in the 1848 will of Samuel Varner, which I transcribed below. 22 enslaved people are listed. I found no appraisal documents online to determine age, but perhaps this post can help descendants locate further information. Another earlier will for John Varner contains the names of a smaller number of those he enslaved. Tharin’s Marengo County Directory for 1861 has three white Varner men living on M’Kinley: Benton Varner, mechanic, Ransom Varner, planter and James Varner “(deaf and dumb)” planter.[4]

Note how the young girl Emely is selected to be an enslaved assistant for Varner’s mute children, so disability is yet another permanently assigned duty. Or were there additional services intended, given Varner’s words at the end of his will: “Should there be an increase in property before my death…”?

Will Record A, F291 Will of Samuel Varner [1848]

Marengo County

Will of Samuel Varner, Decd

In the name of God [ ] I Samuel Varner of the county of Cahaba and the State of Mississippi, considering the certainly of life yet being of sound and perfect mind and memory do make and publish this my last will and testament making all others heretofore made no manner and form following (that is today). First I do give and bequeath to my two daughters Sara Bevel formerly Sarah Varner and Martha Lassater formerly Martha Varner the Sum of $2 each — Second I do give and bequeath to my Sons Joseph Varner, James Varner, John Varner also my said daughter Mahala Varner and Minerva Jane Whitley formerly Minerva Jane Varner the following and all Estate to wit one tract of land [Selnato?] lying and being in the County of Marengo in the State of Alabama, Consisting of one hundred and twenty acres, to wit — adjoining the now named Bevel tract of land which Said land the [Datoso?] road sent through the East corner of the same Also twenty two negroes to wit four negro men Nat. Ransom, Dave and Alfred & the following negro women and children, Emily and her six children to wit: Candis, Caroline, Norton, Emeline, Adaline and Mary Frances Courtney. Matilda and her two children, Levi and an infant girl[;] Fanny and her four children: Allen, Fairchild and Mariah and an infant and Mary and her child Spenser together with all my stock of every manner and description whatsoever with all my farming tools waggons carts plows and every manner of implement or thing needful and necessary for the carrying on the same and all my household and kitchen furniture Saving the beds and furniture with all monies, debts due to me owning in any manner or description whatsoever to have and to hold to my Said Children of the Second Bequest mention to them and items forever Subject to the following hereafter restrictions. I desire that when I depart this life that my remains be buried in a decent and Christian like manner and that all my just debts be paid before a division of my estate, and it is my desire that at my death the negro girl Emely shall belong to my daughter Mahala at her appraised value and shall answer So much to her portions of Said Estate in a final division, and it is my desire ^that Mahala have one bed and furniture and also James and Minerva Jane Whitely take the Same as Specific legacies and not come with a general division— and as my Sons Joseph Varner, James Varner, Mahala Varner are unfortunate being deaf and dumb and it being somewhat doubtful that no law whether they can take by the will. I do hereby constitute, nominate and appoint my son John Varner and my son in law Decator Whitely trustees for them and on their behalf to receive their intended portions of my estate for them & their use and benefit and in case one or both of said trustees should die or refuse to act then it wish that a proper count should be applied to competent to protect them and their property. – It is further my will and request that often deducting Specific Legacies and paying off funeral expenses & debts on a division of said Estate. Should any one depart this life without heirs the portions of said child it is my will should lapse in common to the equally divided will contained in the Second – bequest and it is further my will and request Should my life be Spared by providence and should there be an increase of property before my death, My desire is that it lapse in common to the equally divided with those contained in the Second bequest and in case of one’s death his share to his or her children — And I do lastly appoint John Varner and Decator Whitely Executors of my Estate in this my last will and Testament. Witness my hand and seal the 18 day of July 1848

Signed Samuel (his X) Varner, Seal, Signed Sealed and delivered

The Estate of James Varner, 1827

The earlier 1827 subdivision of “The Estate of James Varner” includes mention of a son also named Benton Varner and several minors. There was a writ for Letters of Administration and Lorian Tibbs, Elizabeth Moon with Wright Moor and Matilda Varner appear as heirs; Martha Lindsay was named as James Varner’s wife.

Four persons enslaved by this Varner family were:

Nancy

Ben

Isom

Peter

.”.that there are slaves name by Nancy, Ben, Isom and Peter cannot legally be divided and on motion of the Administration it is therefore ordered, by the Court that an order of sale do to sell” [5]

Potential Resources

As additional papers were not included in the court records, and as it is a collection which is not complete, additional documents may exist, dispersed across the Special Collections of colleges and universities. There are two collections that feature Varner family papers, one at James Madison University, and the other, Campbell and Varner family papers at Virginia Military Institute . From the overview and information provided here, perhaps an interested descendant can take it back further through a combination of research and DNA testing.

A call to the libraries can confirm if there is relevant material. For the Varners of VA, while it is said there was no ownership of enslaved people at Stony Man Creek, unlike the remaining areas of the district in 1860. Robert H Moore’s post “Page County’s Appleberry/ Applebury men in the USCT.” notes some 30 men who served in the United States Colored Troops were born in Page County. [8]

Click on the bold link to see the Finding Aids for each collection:

Varner Family Papers -1774-1933 SC 0129 – Page County, VA James Madison University:

“The Varner family of Page County, Virginia was of German descent, and their name appears as early as 1801 on records of the Antioch Christian Church near Stony Man Creek, Virginia… Despite wide-spread anti-liquor sentiment in the Shenandoah Valley in the nineteenth century, the Varners operated a distillery.”

Campbell and Varner Family papers MS-0282 – Lexington, VA Virginia Military Institute [9]

“Robert Henry Campbell of Lexington, VA; shoemaker; served with Rockbridge Rifles during Civil War (1861 only); discharged due to illness (tuberculosis); Clerk, Quartermaster and Treasurer at the Virginia Military Institute, 1864-1870; d. 1870, age 28, Lexington, VA.

Charles Van Buren Varner, b. Lexington, VA. 1838; served with Rockbridge Rifles during Civil War; cabinetmaker; carpenter at VMI; d. 1907, Lexington.

The families were related through the marriage of R. Henry’s sister, Augusta, to Charles V. Varner.”

Emanuel Montee McDuffie: from AL to NC

Mrs Della McDuffie’s husband, William ‘Snowball’ McDuffie’s uncle– Emanuel Montee McDuffie — was among the people that left Snow Hill, precisely because of the efforts of William J. Edwards. After graduating from Snow Hill Normal and Industrial Institute, like his mentor, he became Principal of the Normal and Industrial Institute in Laurinberg, North Carolina, where he lived the rest of his life, until his death in 1953. This is not to say he escaped experiencing or knowing the potential violence of Jim Crow. His photo is on the upper left of the group, and appears in William J. Edwards’ Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt. (1919)

A Change is Gonna Come

I can think of no better way to end than to leave you with Sam Cooke’s A Change is Gonna Come. These posts were written to honor the resilience and the survival of these ancestors, and to help write them back into history. “The arc of history is long but it bends towards justice.”

“…There been times that I thought I couldn’t last for long

But now I think I’m able to carry on

It’s been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gon’ come, oh yes it will”

QEPD

References

- William J. Edwards. Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt. Electronic Edition, Documenting the American South.

- “History”. Alabama 1867 Voter Registration Records Database. http://archives.alabama.gov/voterreg/index.cfm

- Index, Alabama 1867 Voter Registration Records Database, http://www.archives.alabama.gov/voterreg/results.cfm

- Richard Varner and Lucy Varner marriage certificate. Ancestry.com. Alabama, County Marriage Records, 1805-1967[database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016.

- Tharin’s Marengo County Directory for 1860-61. https://sites.rootsweb.com/~almareng/marengodirectory.htm

- Will of Samuel Varner, 18 July 1848. Film: Alabama County Marriages, 1809-1950, 005330947, item 2 image number 305. FamilySearch.org

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-L15D-8DN?i=304&cc=1743384&cat=211258 - The Estate of James Varner, 1827. Alabama County Marriages, 1809-1950 Film #005330947 image number 189. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G15D-PCW?i=188&cc=1743384&cat=211258

- “Remaining property of said estates” https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G15D-P4K?i=190&cc=1743384&cat=211258

- ”District #3, Stoney Man – There were no (0) slave-owners and no (0) slaves” Where Were the Slaves in Page County in 1860? http://www.geocities.ws/cenantuaheight/WhereWereSlavesPage1860.html

- Robert H Moore “Page County’s Appleberry/ Applebury men in the USCT.” https://toolongforgotten.wordpress.com

- Note collection is on deposit from the Harrisonburg-Rockingham Historical Society.