On the trail of compassion and wonder: a meditation

Lately, I’ve been pondering how a broader historical framework for the genealogies and family histories can make displacement visible, particularly for identities shaped by the experiences of diaspora and migration.

Shouldn’t we ask questions about how beginnings are constructed? What’s the significance of an origin story? Who gets to tell about the dawning of a deeper historical consciousness among people? For whom does this story matter? Stories are containers for memory, with purpose.

I want to speak to the depth of this experience not because this perspective grants a sense of ‘survival beyond the odds’, but because when one listens to the bits of histories encoded in our stories and in the genes of our ancestors, these experiences can instill both compassion and wonder.

In turn, compassion and wonder feeds the hope of survival, can enable sympathy, free suppressed identities, and through this recognition, foster social change. Our family histories contain worlds within them and perhaps answers that can help us heal in the present.

2.

So, how best to convey and define this complexity? There are so many questions to consider when pondering how to proceed. How can we locate and embrace the foundations created by Indigenous ancestors who kept a particular world view embedded in how they lived? Who can guide us on this journey? How do we come to terms when we discover our enslaved ancestors? Of those who were enslavers?

Our task is to quilt together the narratives of survival and remember those that came before us.

These ancestries, family histories and narratives are more visible today thanks to technologies of social media and the regeneration of concepts out of these deeper pasts. But more needs to be done to unfold the hidden margins of these narratives and reveal nodes of connections- location, place, time so that you becomes we. We are a constellation of microhistories.

3.

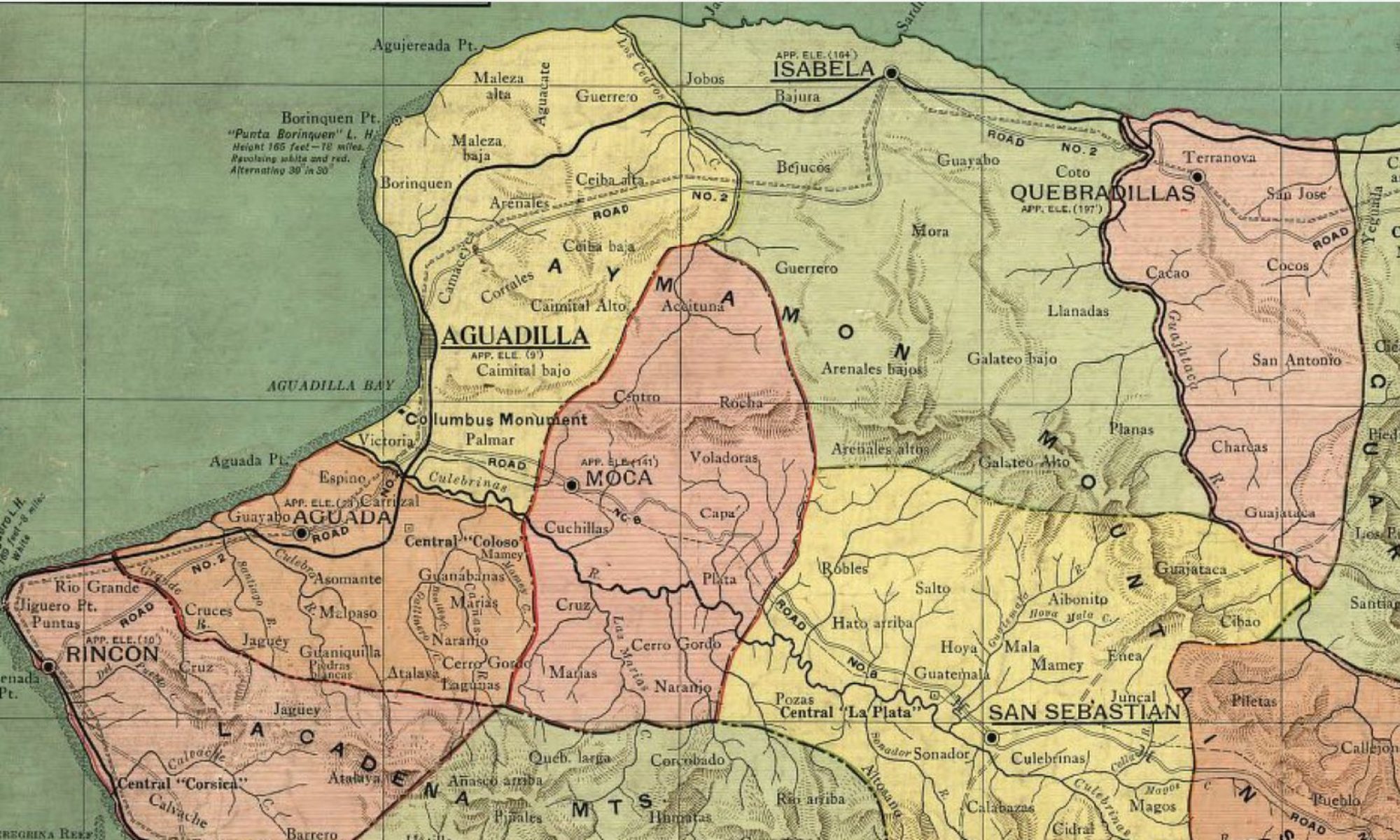

For many Puerto Ricans / Borincanos / Tainos who identify as the descendants of pre-European Boriken, already a blend of Native and African peoples, there is a growing recognition of self and community that stands in relief to a backdrop of colonization.

Indigenous identity is long denied because many grew up hearing the stories of extinction, then some deemed it an impossibility because it was not 100%. What happened however is Taino people were not gone, not frozen in time and continue to incorporate change in the present. There’s a culture and the question of language, which doesn’t negate a continued presence. This identity undergoes acknowledgement and recognition both on and off the island with the situation exacerbated by the pandemic. There’s a level of acknowledgment rather than a challenge, and communities that confirm continuity, a slow shift over the decades. Growth and regeneration continues.

4.

There’s extraction as a process constantly mobilized by different interests across time. Key to destroying the landscape is forgetting our fundamental interconnectedness from the seemingly inert to overtly active lifeforms. One prays for a respite from the machine of capital, from the desire for gold that threatens El Yunque, a tropical rainforest and sacred space for the Taino people. The land everywhere needs to heal and needs its stewards.

Historically, assimilation was the order of the day in policy imposed on Puerto Rico, an echo of how the U.S. dealt with the nations contained within its own borders. Assimilation is an old multifaceted story whose journeys can cost us the past, its details trapped in bits of oral history. What are we remembering? What do our ancestors tell us today?

5.

The backdrop of change is a constant. It goes from enslavement to industrialization to a globalization that traps and impoverishes many. Today one can begin to lay claim to this heritage while gaining visibility with less certainty of disenfranchisement. And because of technology, we can make connections with others that increases our chances of survival through the progressively larger gatherings that take place across the country.

This connection can be an antidote for the historical amnesia that fades with accountability and the remembrance of survival. Can knowledge stop trafficking? Can memory heal? To receive and share their stories, heal and connect is a blessing. What lessons come from the worlds our ancestors inhabited? How are you we?

Seneko kakona (Abundant blessings)

Courtesy: Martin Veguilla.

Discover more from Latino Genealogy & Beyond

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Reply to “Calling the Ancestors”