This was a busy month! On Tuesday evening, I was a special guest on Shamele Jordon’s Genealogy Quick Start on the Migration and Names episode, talking about my third great grandfather in The Many Names of Telesforo Carrillo, based on a previous blog post. She is an amazing host, and I love her energy. Michael John Neill did the first part of the show, “Benjamin Butler Serves Research Suggestions” making suggestions for locating and verifying a very mobile ancestor who lived in several states over the course of his life.

While I spoke for just a half hour, i’m amazed at how a very long time researching ultimately distilled a story out of documents finally brought together. Thanks to the help of cousins, I pulled together documents to understand more about the struggles that each generation faced. Self identification and self determination weave through the lives of my ancestors. As a child in the South Bronx, I did get to meet Telesforo’s daughter Catalina, my great grandmother, who lived to be 104 years old. I ended with my grandfather’s 1925 passport, a folded page with the only photo of his first wife, Carolina Dorrios Picon and their three children, Bobby, Gloria and Sylvia Fernandez, in a photograph that is now a century old.

There are 213 episodes of Genealogy Quick Start, full of resources and recommendations for your browsing pleasure!

Rediscovering Latinidad released their Kissing Cousin episode– Season 7 Ep. 8 – Cuando los primos se exprimen: La endogamia y el matrimonio entre primos, and I enjoyed talking with hosts Eduardo Rueda and Jellisa. Check it out as we go full cringe with endogamy and cousin marriage! This premier podcast about Latino genealogy, culture, heritage and rich layers of intersectionality also has a Patreon. With seven seasons of podcasts, Rediscovering Latinidad is a great resource for learning more about family history, with links for additional information on each episode page.

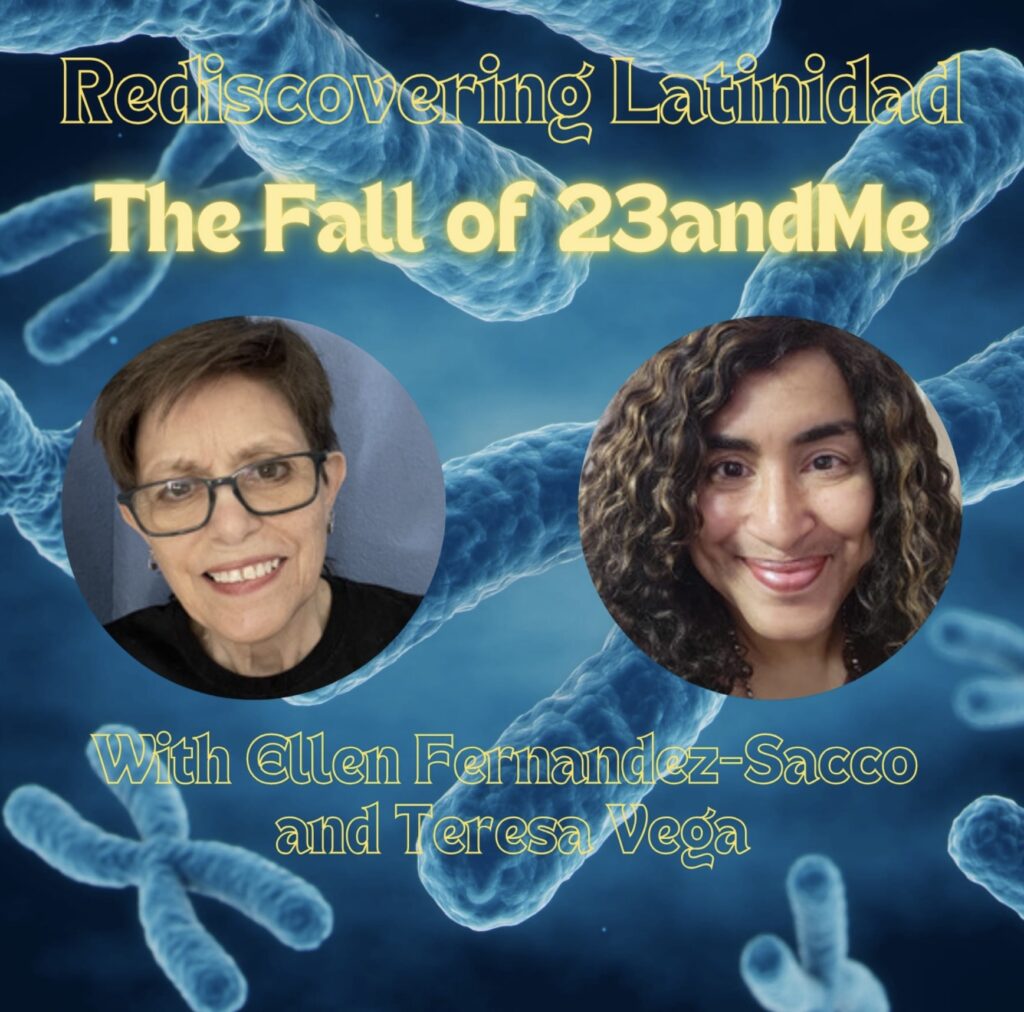

Rediscovering Latinidad also rereleased their most popular episode from Season 7 Episode 10, La Caida de 23andMe/ The Fall of 23andMe, with guests my cousin Teresa Vega and I. Teresa’s extensive knowledge of DNA and complex family histories adds to the discussion. Check out her blog, Radiant Roots Boricua Branches for fascinating research on Revolutionary War ancestors, ancestors from Madagascar, and deep dives into family history.

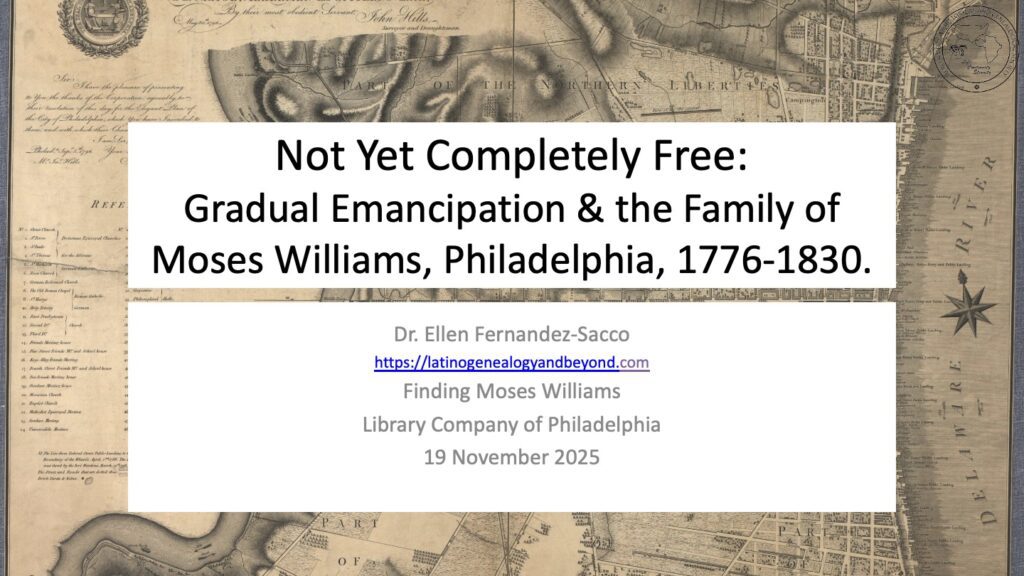

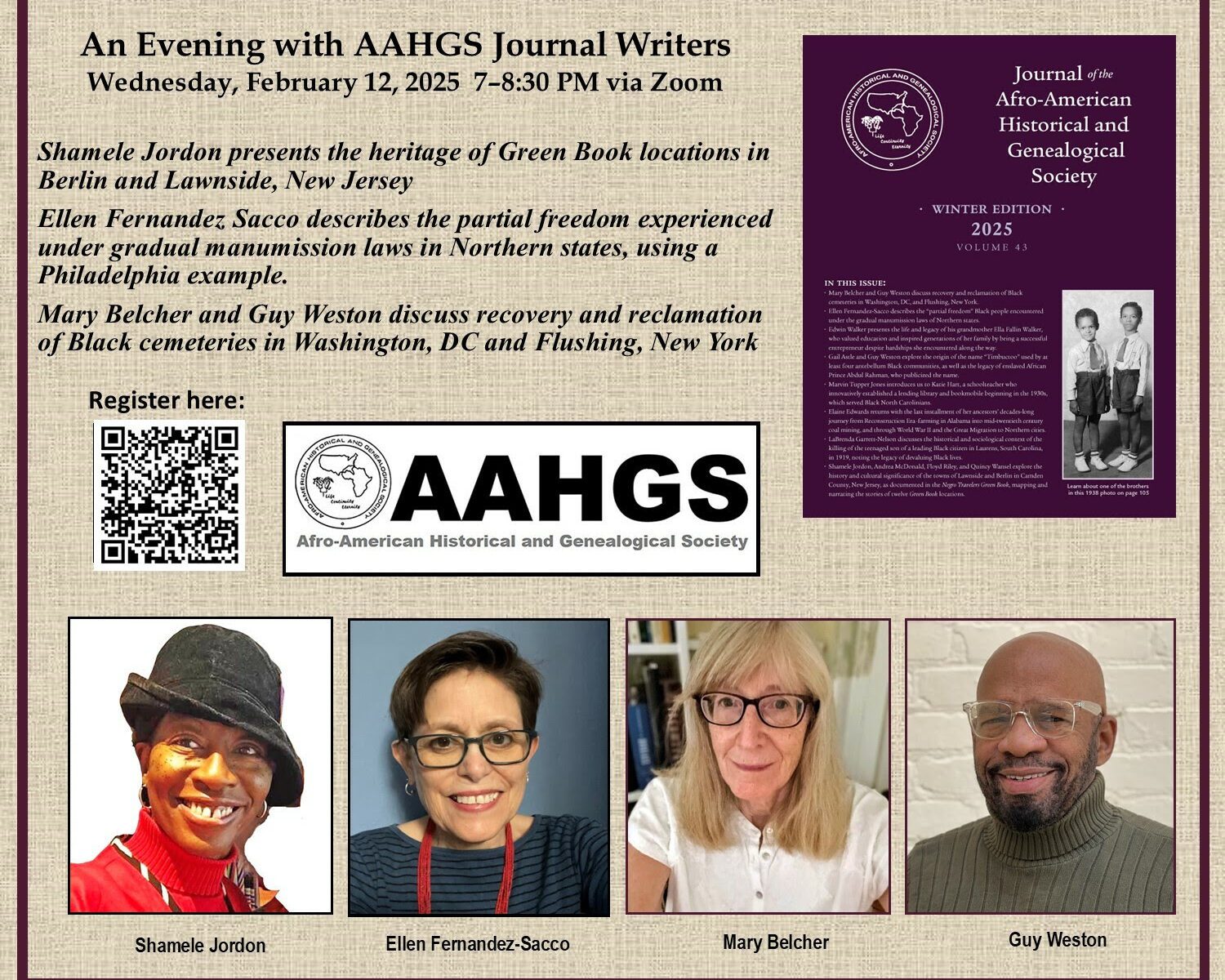

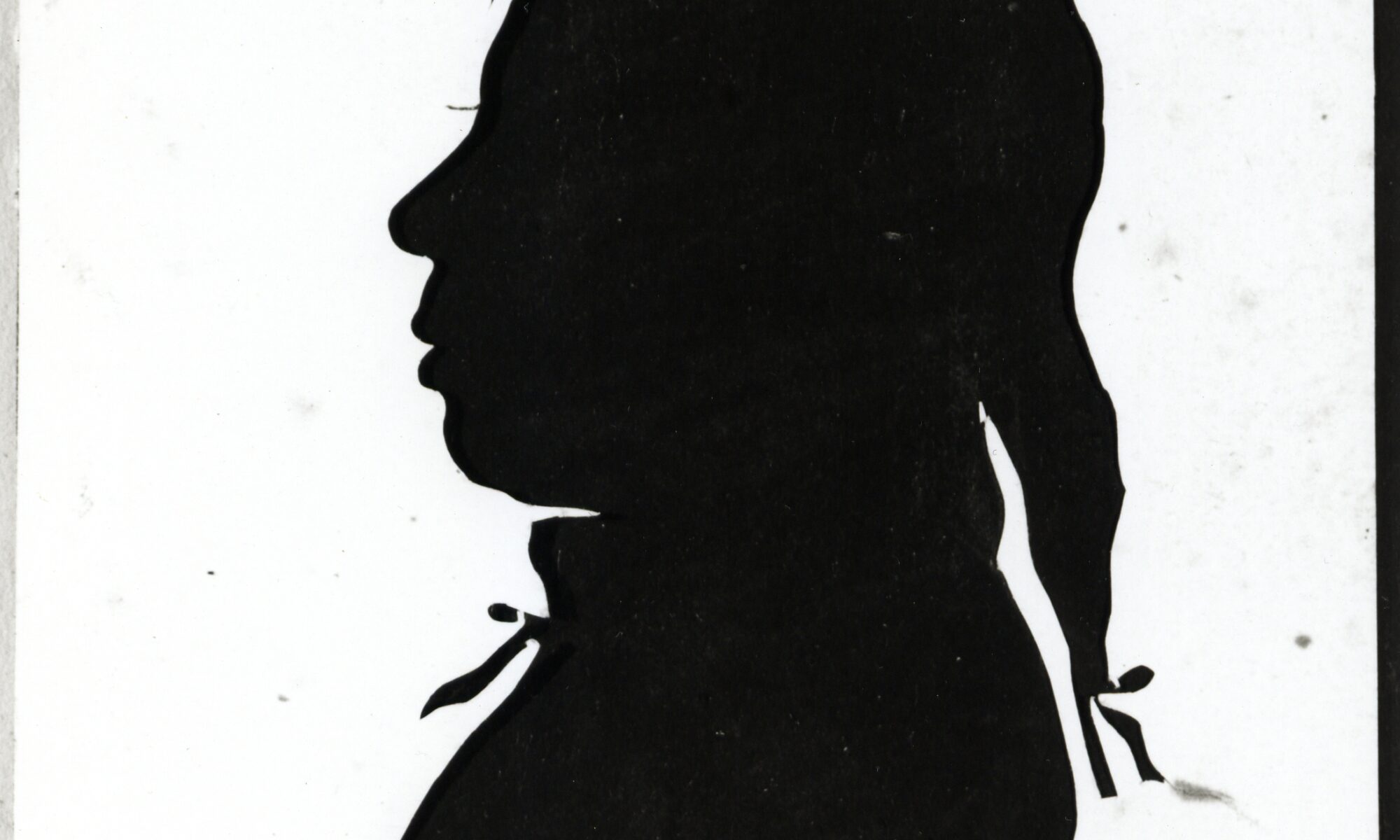

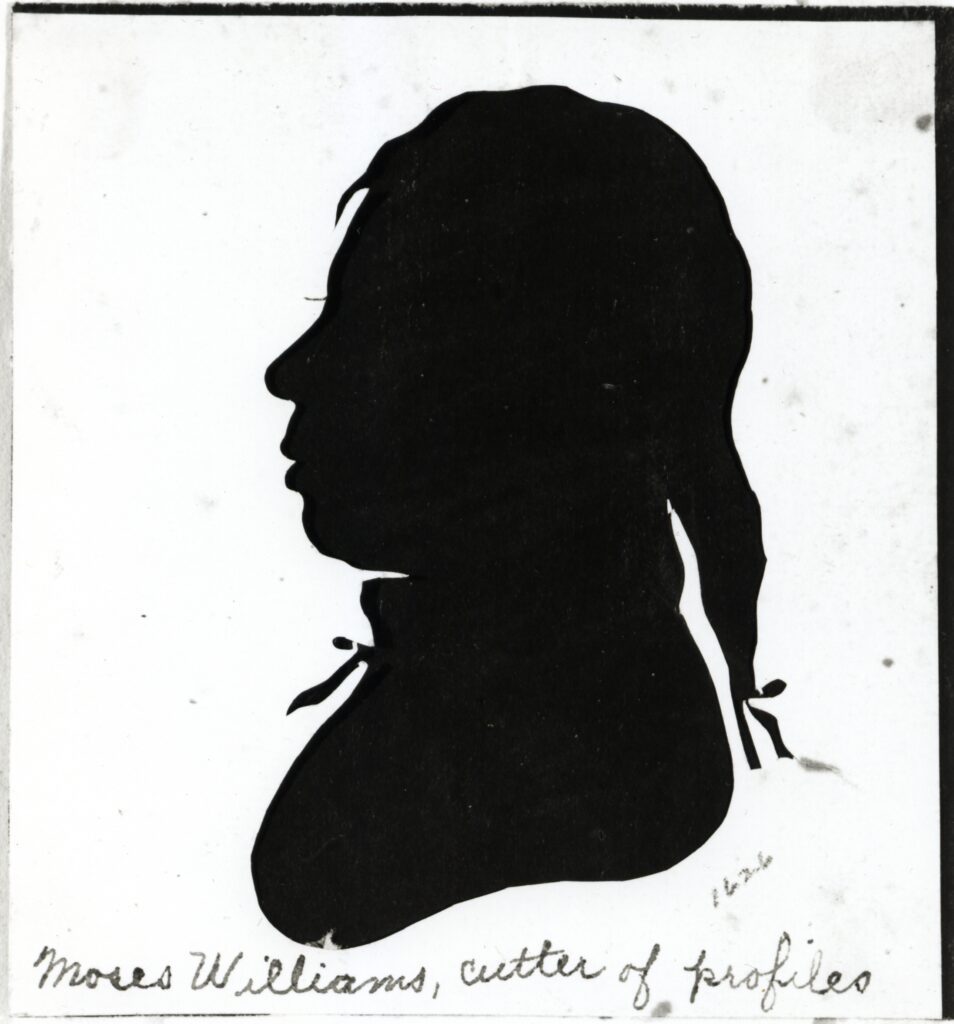

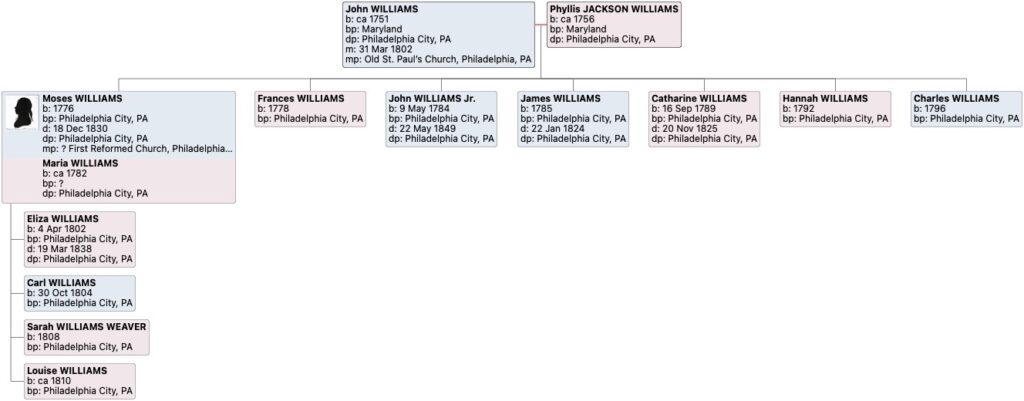

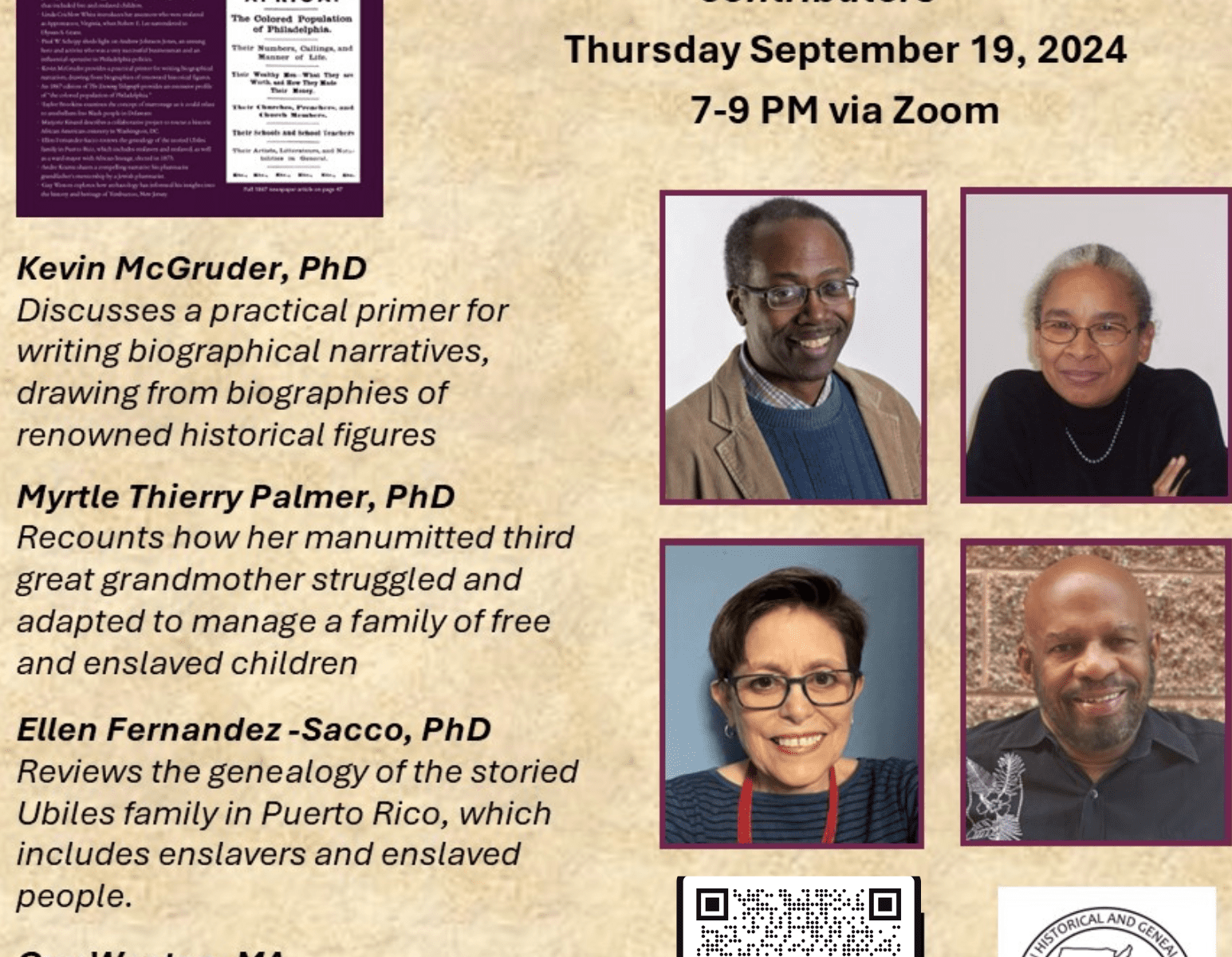

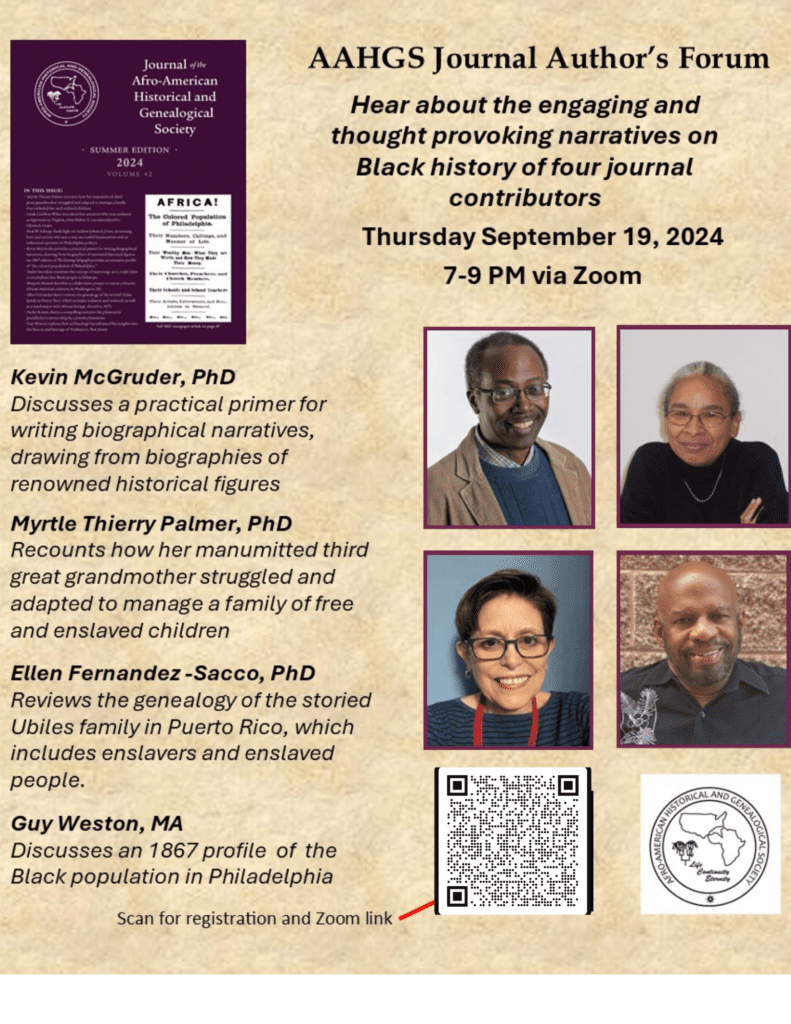

On November 19, I participated in the Library Company of Philadelphia’s virtual symposium Finding Moses Williams, along with four amazing scholars, who shared new insights on his art, life and family. He left a considerable body of work, and perhaps, descendants. So much to learn from these talks!

Here’s a list of the presentations:

Carol Soltis, Finding Moses in the Peale-Sellers family album.

Nancy Proctor, Presenting Moses at The Peale Baltimore.

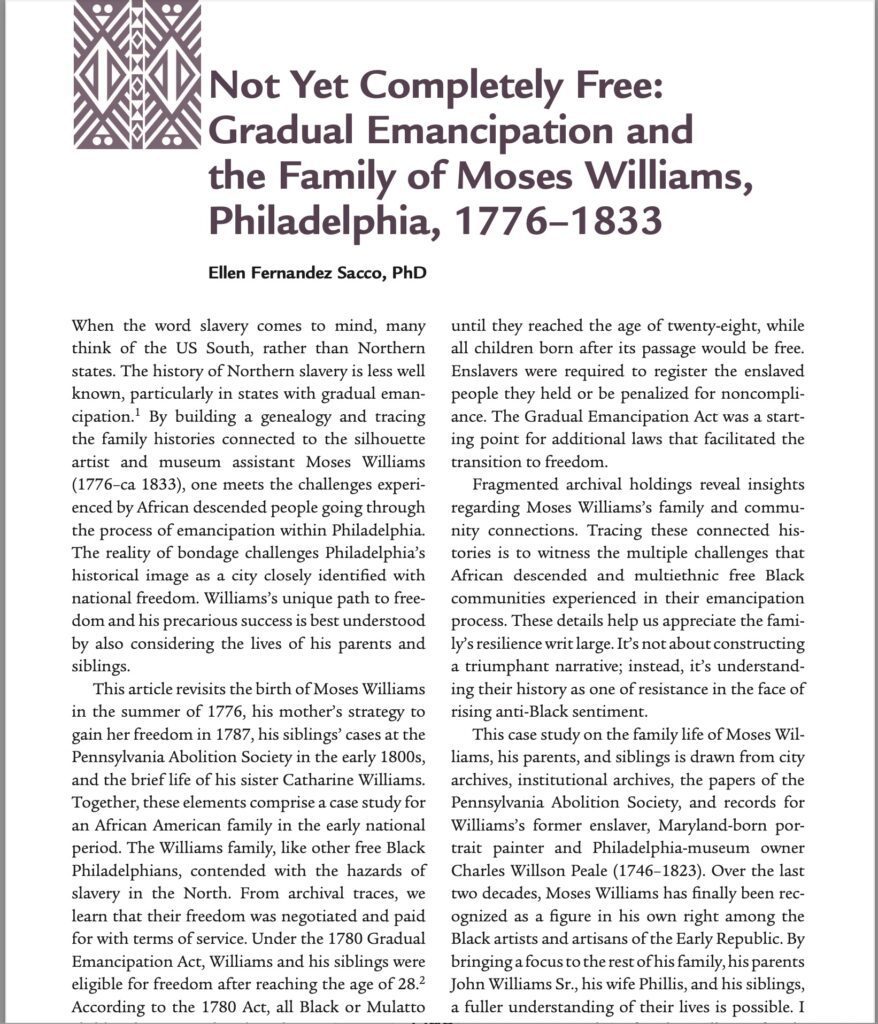

Ellen Fernandez-Sacco, Not Yet Completely Free, The Context of Gradual Emancipation & the Family of Moses Williams 1776-1830.

Dean Krimmel, Locating Moses Williams in Philadelphia, new information about Moses Williams’s life and death based on a re-examination of Philadelphia’s primary sources.

Lauren Muny, Moses Williams, A Technical View.

View the Finding Moses Williams symposium on YouTube : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLxsuixugCk

ps just replaced the link for the symposium, and they’re working now!

Wishing you a very happy December! Seneko kakona!