Before I start: The view from here, some context

In trying to assemble a history of an organization from fragments, I’m grappling with slippage, the way that things unsaid haunt every space, how the unsaid is supposed to be gracious, but hides a different cruelty. It’s working with systems that require violence for its completion, a continuation of the machine of settler logics that seek to justify supremacy, enslavement, murder, and rape. Such details are often folded away until a familial connection is revealed.

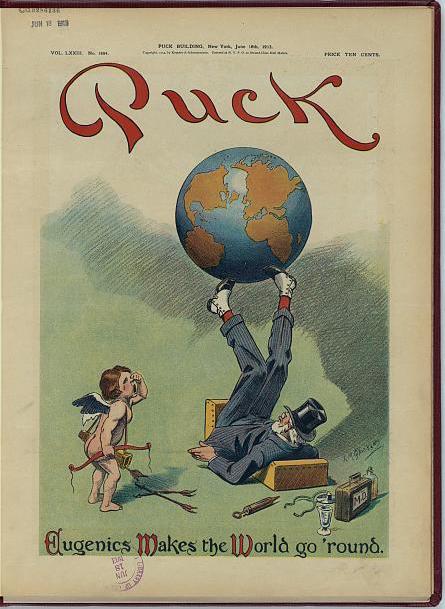

Often the locations where such decisions are made are often comfortable offices or elaborate desert base locations for remote murder and assaults. It is an awareness that hovers over the question of what a Nation is. And societies aim to define and redefine the boundaries. Such colonizing systems also precede the formation of the National Genealogical Society (NGS) at the cusp of the twentieth century, with its familial connections to the Trail of Tears, multiple plantations and governance.

Location Matters

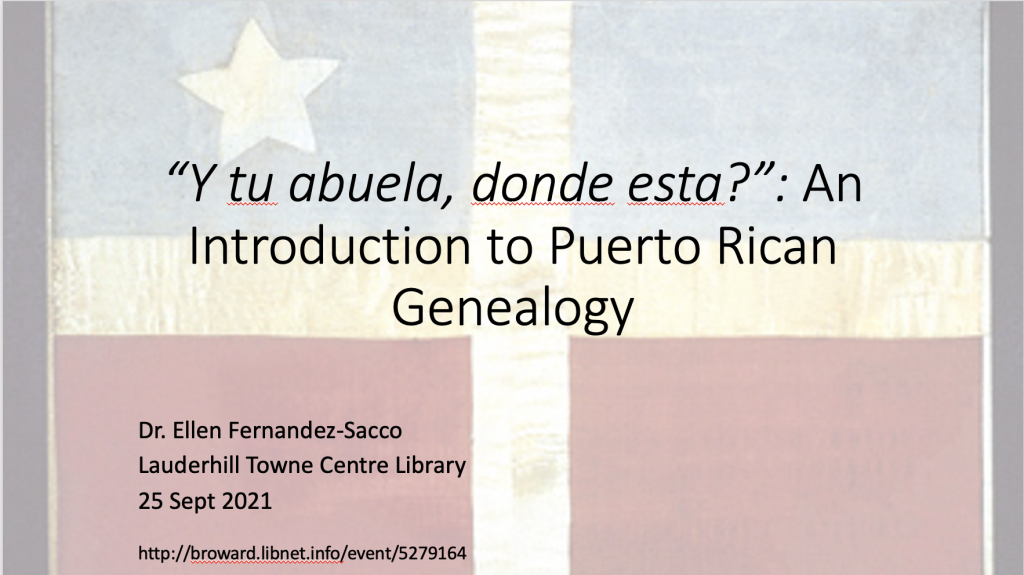

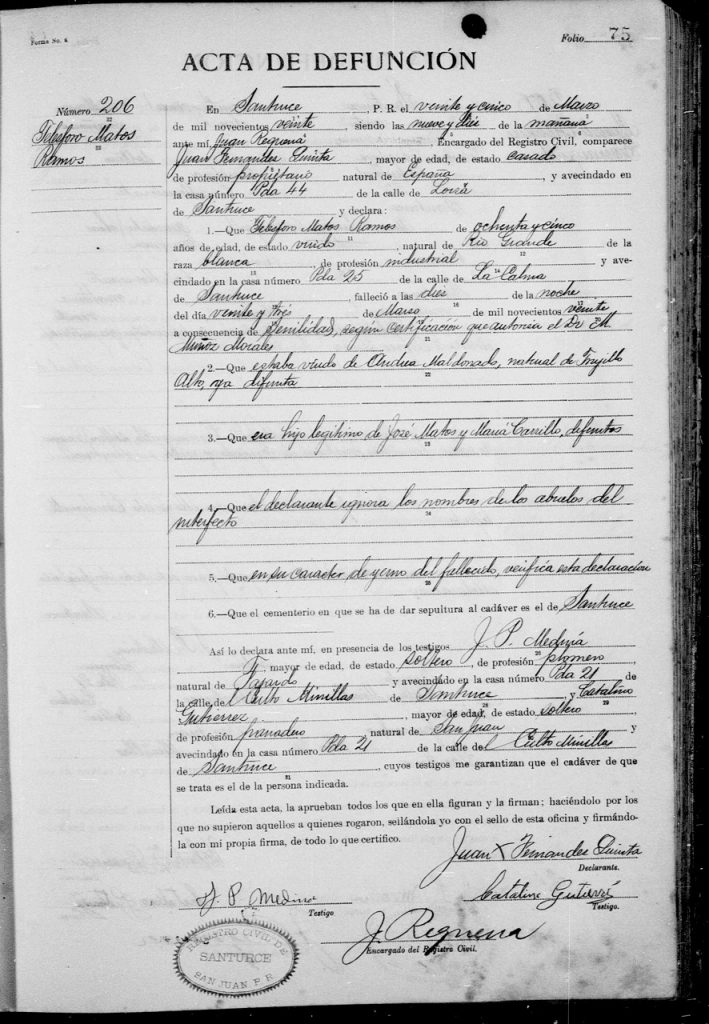

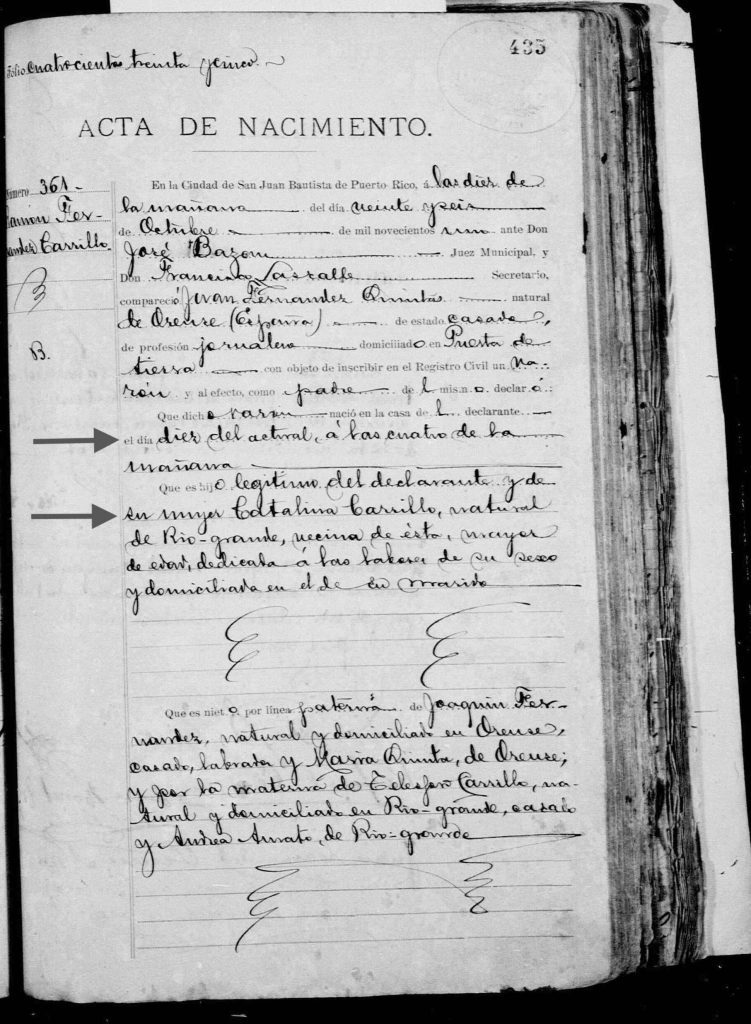

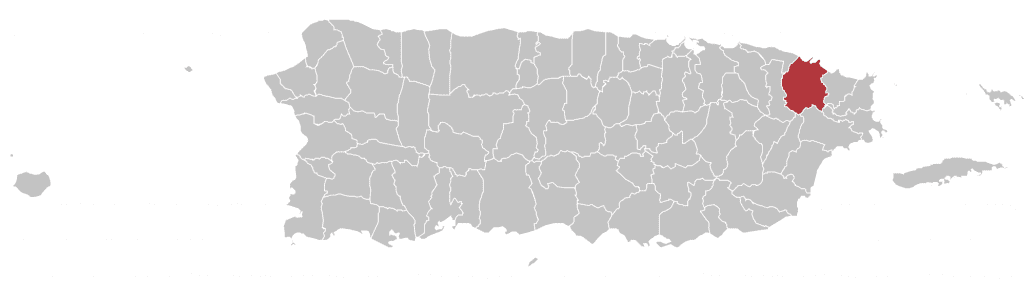

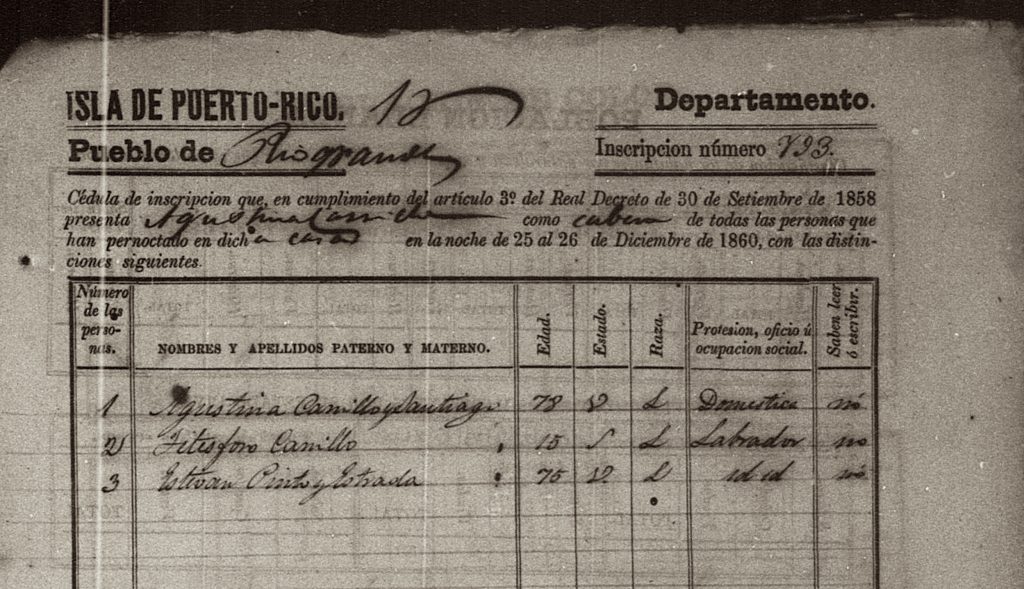

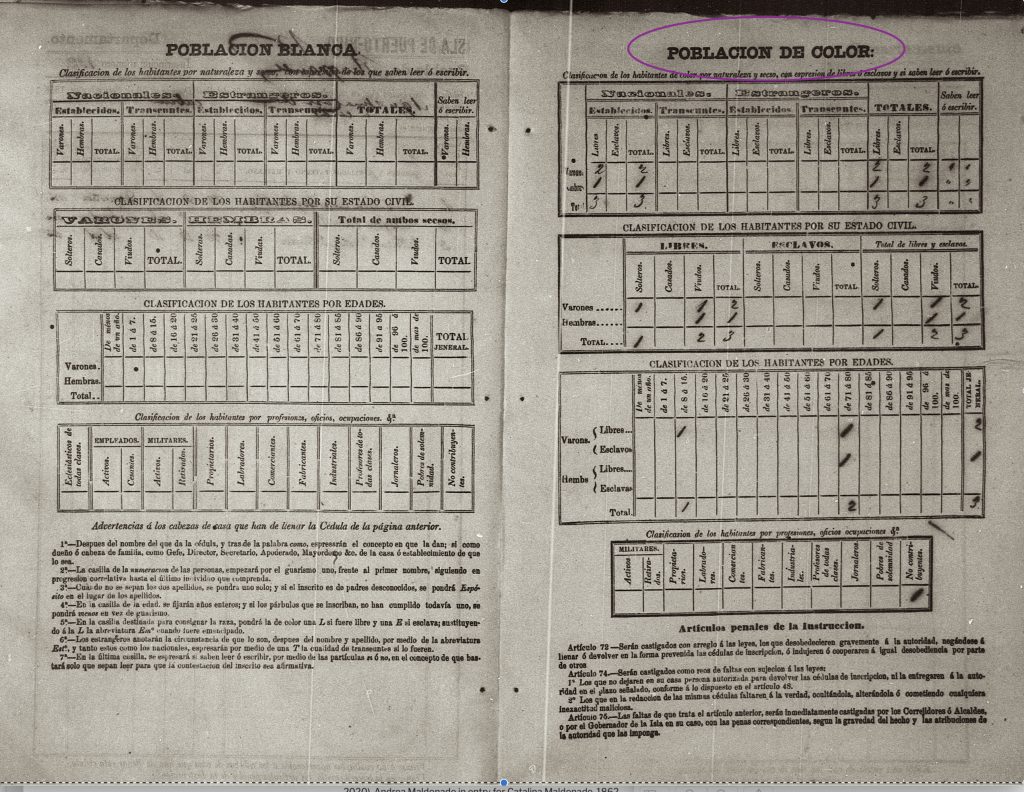

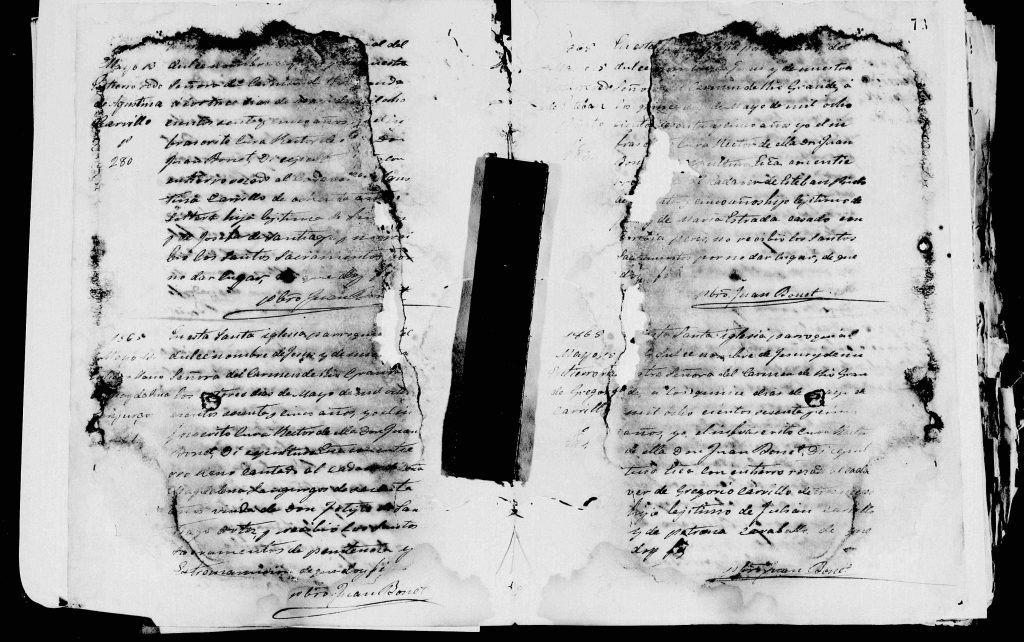

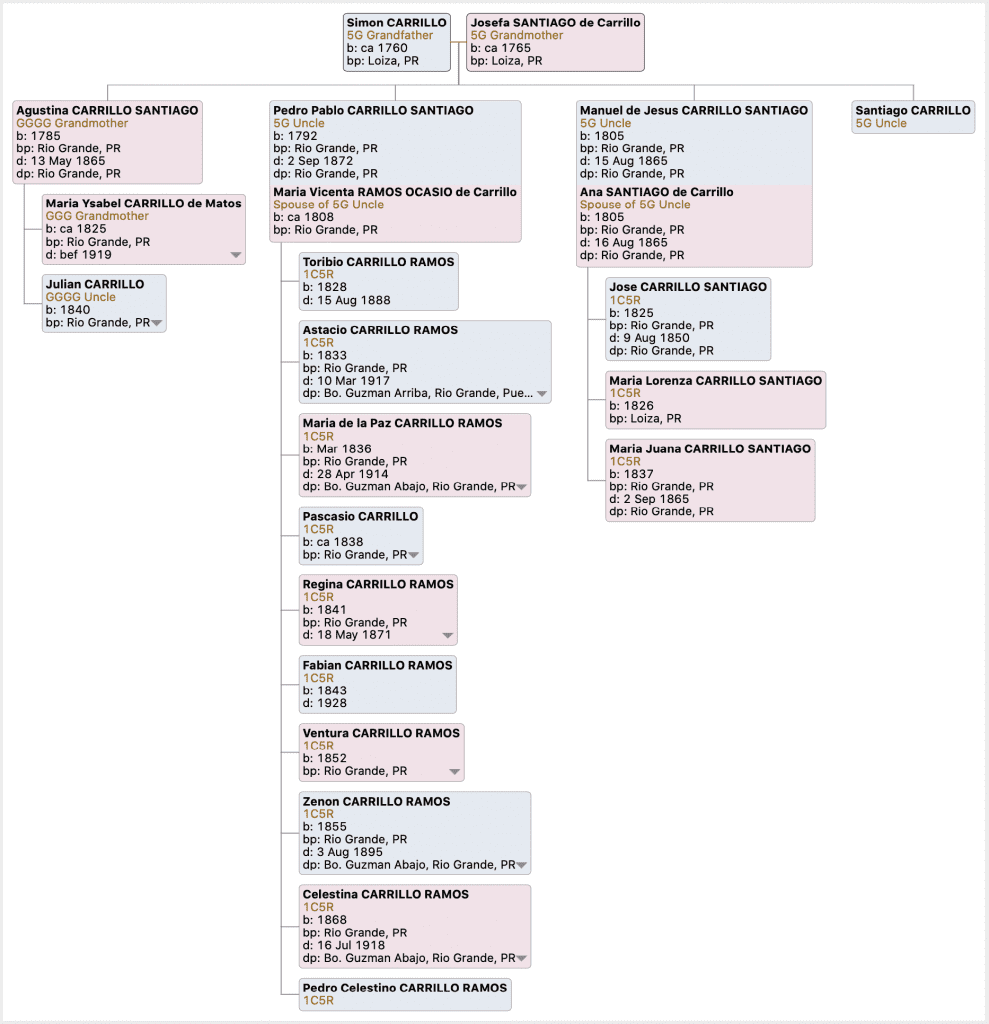

Knowing my Taino ancestry and the creole blends of various ancestors offers a grounding space when faced with the history of organizations. I’m of Native American descent, honor that and study the various diasporas that structure my family tree. I also descend from the enslaved (Juan Josef Carrillo b. Guinea, 1736-1811) and the enslaver (Capt. Martin Lorenzo de Acevedo y Hernandez 1749-1828) within a larger context of colonization, as my family is from Boriken (Puerto Rico). Gaining this knowledge took time, research and service.

The awareness of one’s history contrasts with the history of organizations, particularly those involved with issues such as eugenics, segregation and pushing the Lost Cause (an interpretation of the Civil War from the Confederate perspective). This is part of the National Genealogical Society’s early history. On the other side is the history of Federal employment, and the impact of segregationist policies in Washington DC and how James Dent Walker navigated this at NARA (National Archives and Records Association). Ultimately his knowledge and skills helped to broaden the institutional spaces for BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color) to do their own genealogical research.

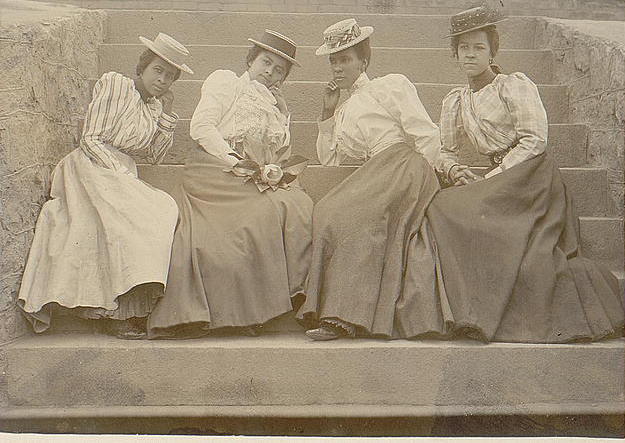

I have talked to several Black genealogists about the other part of genealogical research– the emotional labor of dealing with findings, of telling the stories of ancestors who passed through to emancipation. Of their encounters with people who made life difficult by blocking access to resources, often in a multiplicity of forms that reinforced segregation and at its essence denied a full humanity. This is the larger context of doing this work. This too is part of the genealogical journey. Change can feel glacial in its progress.

The Vote of 1960: Looking Back to Move Forward

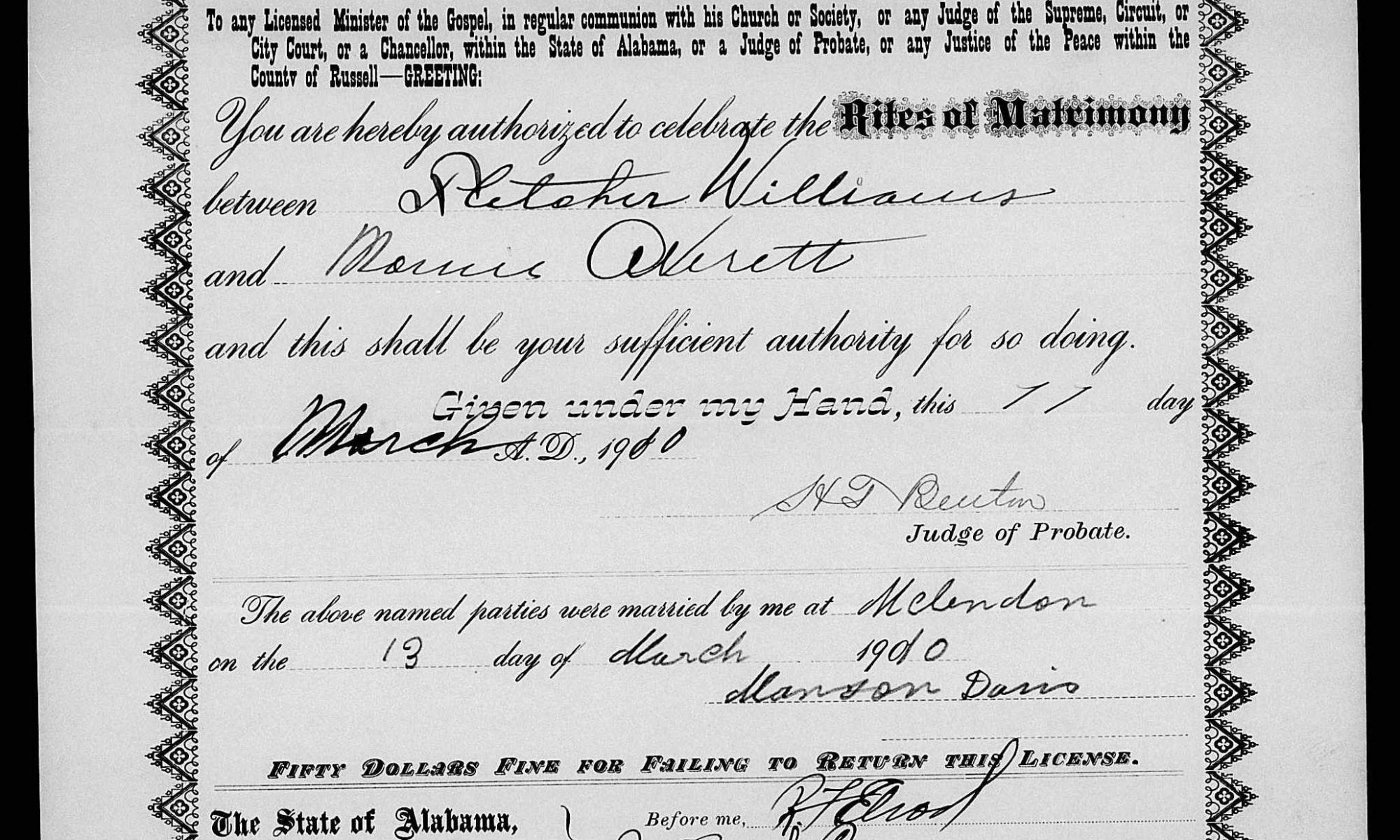

Here I grapple with the silences and statements made by three white women who took it upon themselves in 1960 to mail over 700 members of the National Genealogical Society and encourage them to protest the changes to the language used to define membership. This happened sixty-two years ago, and it is worth a look back.

During the 1960s the clamor for change, like now, was loudly expressed in civic gatherings across the nation. In some locations, anger ripped across cities in the form of buildings lit aflame, people marched. The Civil Rights Movement began in 1954 to work against racial segregation and discrimination across the south and grew into multiple forms. In the south of 1960, many people in power were believers in the Lost Cause and used force to keep people down. And when the Freedom Riders groups arrived in different locations across the South, the use of violence against them by locals and police exploded.

But back to this vote.

This NGS committee, Virginia D. Crim, Bessie P Pryor and Katie-Prince Esker, made the old membership policy explicit:

“the Referendum referred to was held on November [19] 1960. The membership voted on the following:

SHOULD THE NATIONAL GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY SET ASIDE ITS GENERALLY RECOGNIZED PRACTICE, WHICH HAS BEEN IN FORCE SINCE ITS ORGANIZATION IN 1903, AND ADMIT MEMBERS OF THE NEGRO RACE.” [1]

Initially, the National Genealogical Society voted not to open their doors to Black genealogists, a policy held for over 50 years. The then new president, William H. Dumont realized this couldn’t last, and the language that defined who could be a member was changed after James Dent Walker, a NARA civil servant and genealogist applied for membership in 1960. He wasn’t specifically named in newspaper coverage, although the Washington Post’s description leaves no doubt it was Walker. [2] Walker himself never discussed the challenge he set by applying for membership to NGS. He continued to forge an incredible path forward.

Ultimately, Walker became part of NGS’ board, and a nationally recognized genealogist, researcher, lecturer and archivist in his own right, known for his work in African American genealogy. A little over a decade later, he founded the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (Today the African American Historical and Genealogical Society), AAHGS.org that has chapters across the country. [3] This institution proved a necessary space for Black genealogical practice over the decades.

The Press & The Committee

The Washington Post’s article, “Genealogical Group Gets Racial Issue” of 4 November 1960 asked “Is a Negro to join the searchers for the Nation’s family trees? The National Genealogical Society is in a tizzy…about 50 members who felt “controversy threatened to engulf the NGS” proposed a racial restriction clause in their constitution.” Those opposed to admission said “Negroes…have nothing in common with us, genealogically speaking.” Those who favored change in policy “point out the Society is national, educational and scientific; that it is not to be confused with patriotic organizations; that in the pursuit of science there is no room for discrimination…” [4]

Looking beyond the fight over NGS membership, this was a time when nationally, thousands took part in multiple Civil Rights actions in former slave and free states pushing for change. The stakes were high, and some died while others were seriously injured in these actions that insisted on equality. Don’t forget that Black women finally got the right to vote five years later, in 1965.

While these NGS committee members didn’t go out and physically attack BIPOC [Black, Indigenous People Of Color], what actions did they take to maintain white supremacy beyond this administrative act, beyond the organization? Almost always, the families of those who owned forced labor camps from the founding to the third quarter of the nineteenth century are automatically absolved by the focus on the inhabitants of the big house, their genealogy. This telling of local histories goes together with gatekeeping and acts of genealogical segregation of the last century. How far did this committee take their views?

Virginia Crim was also a member of the DAR, where she served as a vice regent for the Columbia Chapter in 1956.[5] She was also a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, established in 1894, and served as a chapter delegate at their convention, held 9 November 1960.[6]

The UDC, a Neoconfederate organization, pursued fundraising for monuments, lobbied legislatures and Congress for the reburial of Confederate dead, denied the violence of slavery, and shaped the content of history textbooks. They insisted on a Lost Cause framework that buttressed Jim Crow laws. They were supportive of the KKK. [7] This contributed to the structural racism that constricted the opportunities and lives of many BIPOC. This too is a legacy of harm linked to NGS’ history in the twentieth century.

Why this history matters

How much does this history matter? In Richmond, Virginia, at 1:30AM on May 30, 2020, in response to the murder of George Floyd and police violence, the anger of some protesters focused on the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, set the UDC facade on fire, and covered confederate monuments in graffiti. The process of removing these monuments across the South accelerated after the protests that erupted in so many locations in the wake of Floyd’s murder.[8]

It shows that representation matters, that there was so much more than what those statues and laws attempted to assert. The implications of this event was global.[9] The times had indeed changed, the demand for systemic change is beginning to be heard. It’s also here, with us, with the DEI Committee, to bring such connections forward, to heal. I have stepped down in order to finish my projects. In the meantime, i’ve joined AAHGS.

And this sea of data generated by institutional conditions washes upon us as we write our microhistories, family histories, genealogies and record the voices of those with ties to these events. Masinato (Peace)

References

[1] Virginia Crim, Bessie P. Pryor, Katie-Prince Esker, Committee Circular, November 30, 1961 [30 November 1960], NGS Archives. Thanks to Janet Bailey, NGS Board Member for locating this document and additional resources for research.

[2] Rasa Gustaitis, “Genealogical Group Gets Racial Issue” Washington Post, November 4, 1960.

[3] Gustaitis, “Genealogical Group Gets Racial Issue.”

[4] For a biography of James Dent Walker (1928-1993) and his oral history, see Jesse Kratz, “James D. Walker: Lone Messenger to International Genealogist.” Pieces of History, Prologue, 10 February 2016. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2016/02/10/james-d-walker-lone-messenger-to-international-genealogist/ Accessed 16 July 2022. Has embedded link to Dent’s edited oral history interview by Rodney A. Ross, James Walker, Oral History Interview, NARA, 27 March 1985.

[4]“Elected Officers.” The Evening Star, Thursday August 30, 1956.

[5]“At Convention.” The Evening Star, November 9, 1961.

[6] “The organization [UDC] was “strikingly successful at raising money to build monuments, lobbying legislatures and Congress for the reburial of Confederate dead, and working to shape the content of history textbooks.” Karen L. Cox, “Setting the Lost Cause on Fire: Protesters Target the United Daughters of the Confederacy Headquarters , Aug 6, 2020 https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/summer-2020/setting-the-lost-cause-on-fire-protesters-target-the-united-daughters-of-the-confederacy-headquarters

[7] Ned Oliver & Sarah Vogelsong, “Confederate memorial hall burned as second night of outrage erupts in Richmond, Virginia.” Virginia Mercury, 31 May 2020.

[8] Balthazar J Beckett, Salima K Hankins, “Until We Are First Recognized As Human: The Killing of George Floyd and the Case for Black Life at the United Nations.” International Journal of Human Rights Education, Vol 5:1. https://repository.usfca.edu/ijhre/vol5/iss1/4/