A supplement for Episode 89: Dangerous Liaisons: Jailbird Relatives and The Freaky Underside of Genealogy. Black ProGen Live! July 30, 2019

There’s no family history left untouched in some way by underground economies and prostitution. Prostitution or sex work, can be understood as a means of survival first and second, an avocation, either by choice or coercion. Beyond the economic question of support, there are questions about the nature of history that can exclude the marginalized worker, questions around ideas of gender, masculinity, power and the network of beliefs and the structure of law that declares it legal, illegal or a fusion of the two. So, if we think about family histories that deal with aspects of an underground economy, it means dealing with variables in time and place. For many this was a temporary connection or situation, a form of employment that was often unpredictable. Only for a select few, was it a situation under their direct control.

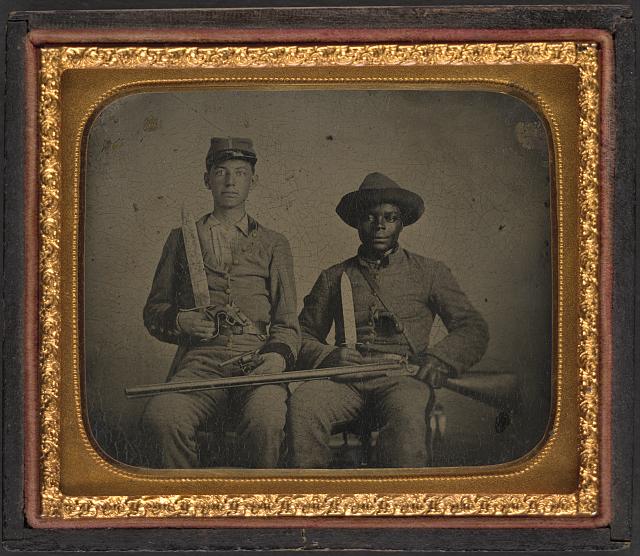

In art, prostitution is the subject of painting, literature, cinema and photography; it shapes the nature of urban, modern experience and informs the realms of tourism and the military. There are stereotypes that circulate in popular culture, in different societies, best viewed as means of defining ideas and assumptions around gender, race and various social boundaries. Looking further back, sexual slavery was also a feature of the transatlantic slave trade that used men women and children, and there’s the trafficking that continues into the present.. Columbus established a sex trade on Hispanola by 1490, with children as young as 9 years old serving as sex slaves.

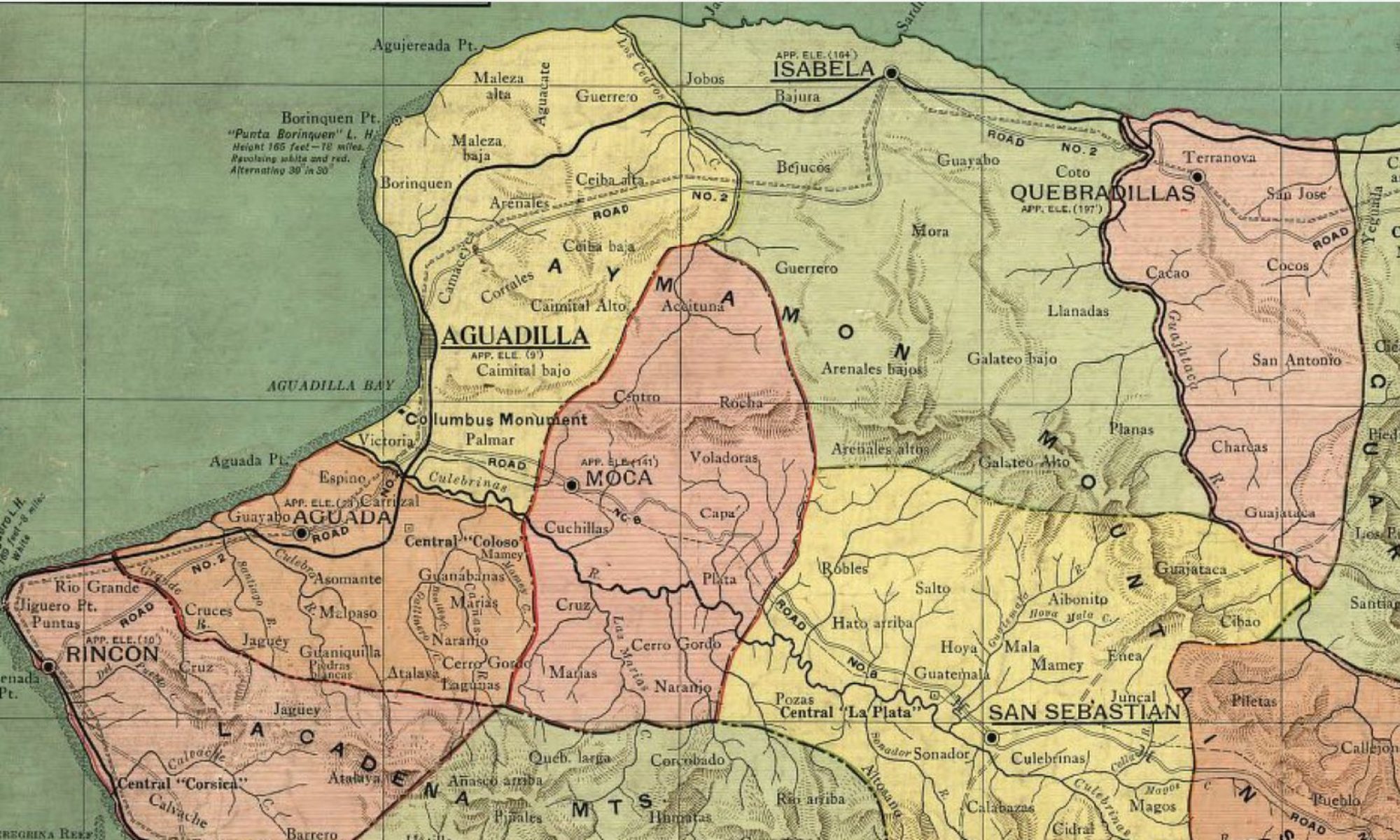

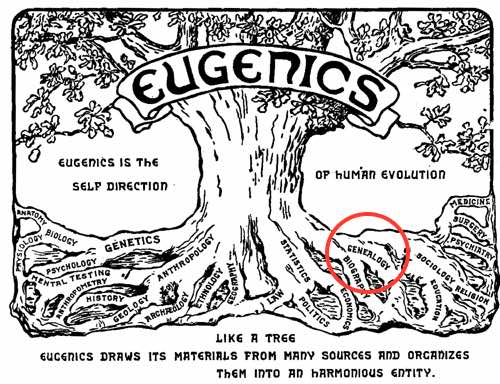

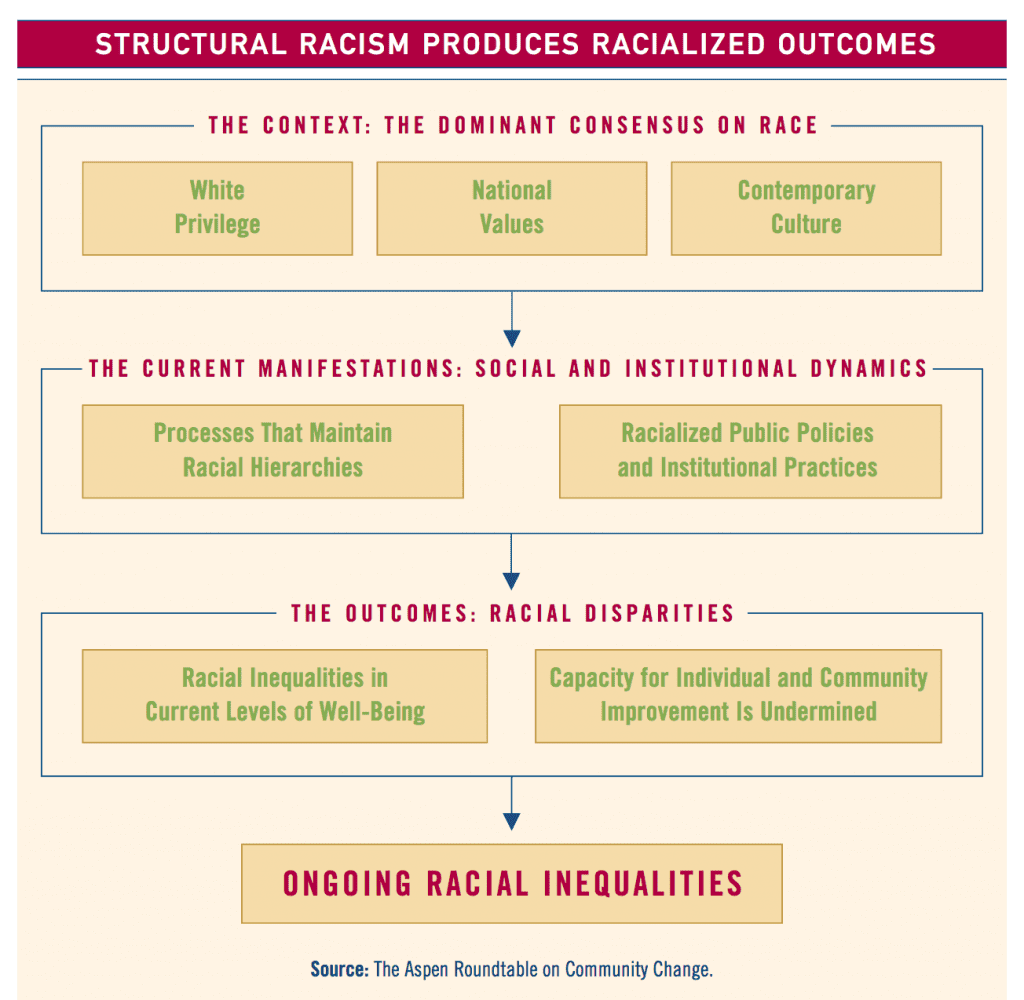

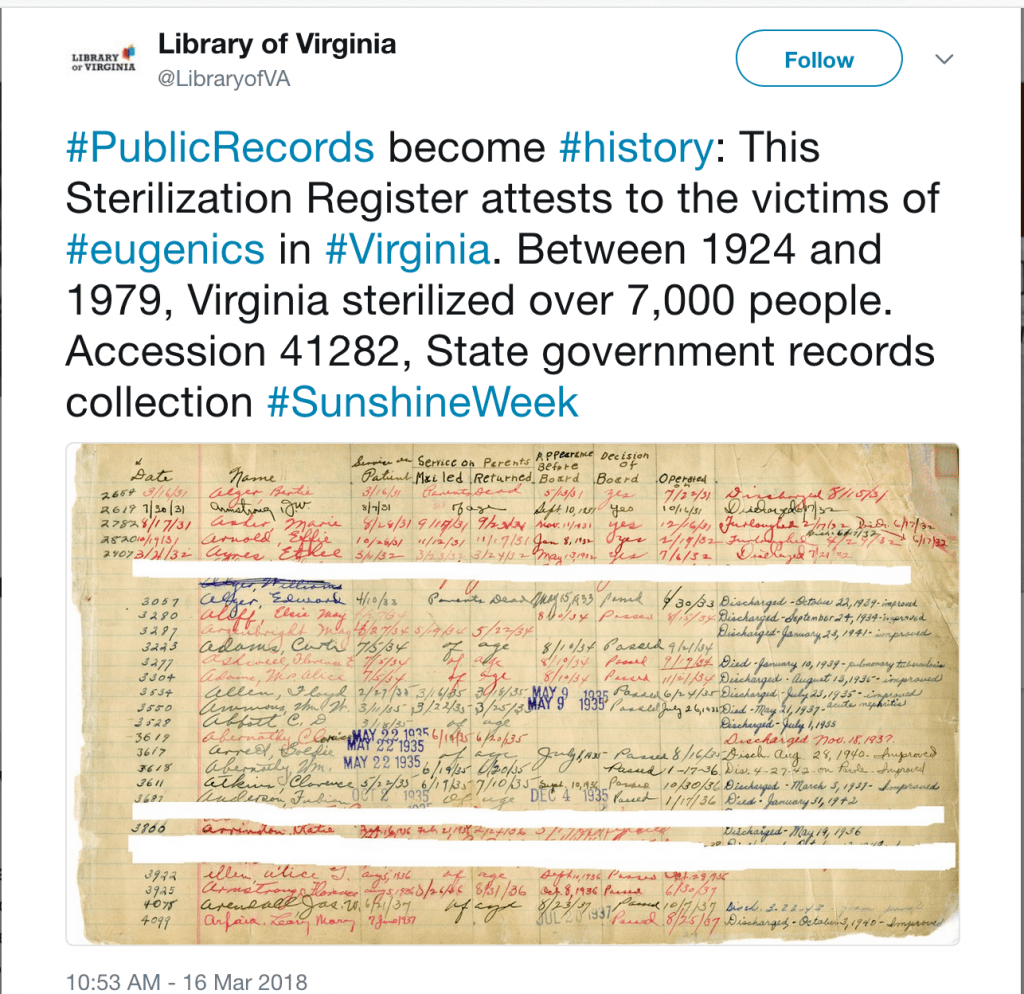

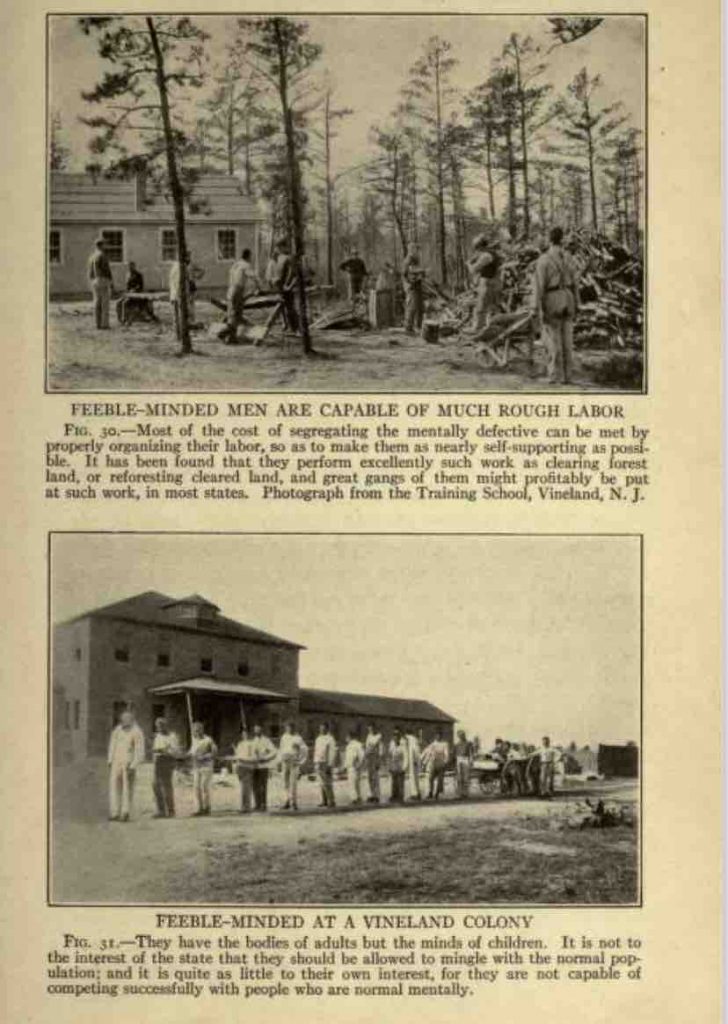

Prostitution as an organized business arrived in Puerto Rico (and by extension to other colonies) with Spanish colonization in the sixteenth century. After the Spanish American War, for example, policing these boundaries of gender and race drew on discourses of eugenics and public health, so that women were subjected to moral judgements, incarceration, forced medical treatment and framed them both as a targeted category of control and as fulfillment of eugenic policies. Any behavior viewed as questionable by women living in poverty, or regarded as promiscuous, were targeted and swept up as a means of social control, even if they never worked ‘the life’.

Family, Context, Options and Motivation

Understanding how illicit businesses like prostitution, numbers running, and black market participation shapes your family history, can open up a history of different social networks, and is an opportunity to understand the various social constraints and options people faced to sell the only thing they had left to sell to survive.

Often there is an economic reason that leaves people in desperate situations, as with the women mantua makers of the 1840s whose poor pay for long hours hand sewing then-fashionable hooded outerwear. As they contended with rising expenses many were left working a sex trade in order to make ends meet. Some were persons who suddenly found themselves without other means of support; still others (a much smaller group) decide on it as a business, contending with the legal structures on the local and national level to keep business going. Employment by any means necessary was for some, key to survival. In Harlem of the 1930s, Stephanie St. Clair known as “Queenie”, “Madam Queen”, “Madam St. Clair”, and “Queen of the Policy Rackets”, ran a numbers racket that kept some 2,000 people employed during the Great Depression, despite attempts by the Mafia to take her empire over. When a young man in New York City, my paternal grandfather kept food on the table for his family by being a numbers runner, the person who brought the bets to the bookie.

Violence & social control

Depending on the age and racial designation, there may be no effort to help or investigate the murder of sex workers, denying justice as well as legal and medical support services to those who remain. Or, there is wholesale denial on offer, as with the so-called Korean ‘Comfort Women‘ forced to serve the Japanese Army during WW2, who went on the promise of factory employment and instead found themselves in harrowing conditions. Yet, acknowledgement and apologies from the Japanese government were not forthcoming. Oral histories are key to knowing and understanding what happened.

Violence, repression and incarceration are also part of the picture, adding to the complexity of understanding the past. Law enforcement was anything but consistent. Conditions vary, whether streetwalking, brothel, escort, and the legal stance per country can exacerbate or support those involved, and class made a huge difference. Military prostitution, child prostitution, trafficking and tourism are other aspects to consider when researching the past. The question of slavery, whether legal condition or condition of labor repeatedly comes up. Studies do show it’s better to have regulation and laws that protect the worker rather than have an illicit trade where it is not those who labor who gain the income.

Finding Information: Some Resources

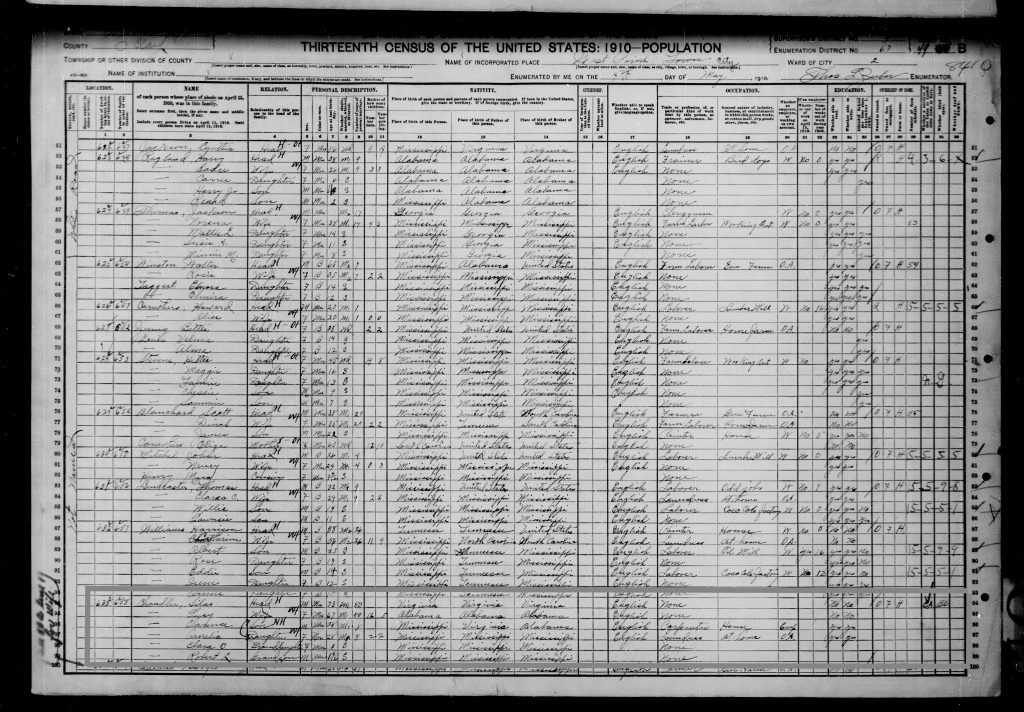

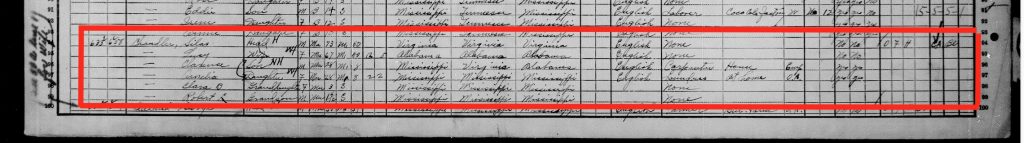

Oral histories, photographs, police reports, newspapers, census and military records, are just some of the materials in various collections that may have information on a family member. As the essay from the Framing Resources site at GMU notes, there is no one class, cultural, religious or social perspective on prostitution, and it’s a field of study that has much to offer in terms of understanding the historical context of family histories involved with the practice, some of it very recent. Also the site provides a small area that lays out some questions helpful for working on genealogical research in terms of the nature of primary and secondary materials you’ll encounter in libraries, special collections both online and off.

Take a look at Tyler Schulze’s Black Sheep Ancestor pages “Search for your Blacksheep Ancestors in Free Genealogical Prison and Convict Records, Historical Court Records, Executions, Insane Asylum Records and Biographies of Famous Outlaws, Criminals & Pirates in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada” http://blacksheepancestors.com

I Dream of Genealogy has a cluster of 7 states (CA, FL, IL, IA, LA, NV, NY) with access to admittedly a small group of free Prison and Arrest Records listed in http://www.idreamof.com/prison.html?src=gentoday

The Internet Archive has over 1400 items in a search result, some of them guidebooks, others, legal statutes published during the 19th century, books and other related materials to download or borrow. See link below.

Also included are the links to special collections on Storyville, New Orleans from the Library of Congress website. Please scroll down towards the end of this post.

This list is not exhaustive, but intended to give a sense of the wide variety of materials and approaches that you can apply to your searches.

Resources

General

“Framing Resources Essay: Case study on prostitution” – Women in World History Website “These varied materials reflect differing class, cultural, religious, and social perspectives on prostitution, especially in the modern, Western world. They tell us what observers thought about prostitution and how their attitudes changed over time. Until recently, there were few personal accounts by prostitutes to provide clues about their varying motivations or their attitudes toward the governments, organizations, or individuals that sought to regulate the practice or abolish prostitution. Oral histories as well as the anthropological and sociological studies that document the lives of prostitutes, many of them from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe and almost all of them poor, have begun filling this gap.”

http://chnm.gmu.edu/wwh/essay/essay.php?c=resources&r=case

Andy McCarthy, “Genealogy Tips: New York City Cops in the City Record.”

“…For the five boroughs, there really is no collection of historical “police records.…”

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2017/08/18/researching-nypd-city-record

NYPL Record Requests: FOIL

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/services/law-enforcement/record-requests.page

Cyndi’s List: Occupations: Prostitution

https://www.cyndislist.com/occupations/prostitutes/

Judy Rosella Edwards, “Genealogy of Communities: Prostitution” Genealogy Today.

https://www.genealogytoday.com/articles/reader.mv?ID=2916

“Researching the Oldest Profession.” Family Tree Magazine

https://www.familytreemagazine.com/premium/researching-the-oldest-profession/

“Prostitution in the Americas.” Wikipedia.

[Note the status of countries as legal, legal and regulated and illegal]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostitution_in_the_Americas

“Prostitution in the United States.” Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostitution_in_the_United_States

“Prostitution in Paris” Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostitution_in_Paris

Andrew Israel Ross, “Sex in the Archives: homosexuality Prostitution and the Archives de la Prefecture de Police de Paris”, French Historical Studies, 2017 (free access)

https://read.dukeupress.edu/french-historical-studies/article/40/2/267/9914/Sex-in-the-ArchivesHomosexuality-Prostitution-and

Elizabeth Garner Mazaryk, “Selling Sex: 19th C New York City Prostitution and Brothels.” 3 Sep 2017

https://digpodcast.org/2017/09/03/19th-century-new-york-city-brothels/

New York State Prostitution Laws

https://statelaws.findlaw.com/new-york-law/new-york-prostitution-laws.html

William E. Nelson, Criminality and Sexual Morality in New York, 1920-1980. Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities.

https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1091&context=yjlh

LaShawn Harris . “Playing the Numbers Game: Madame Stephanie St. Clair & African-American Policy Culture in Harlem”. Black Women, Gender and Families (2008). 2 (2): 53–76.

Bastiaens, Ida (2007) “Is Selling Sex Good Business? : Prostitution in Nineteenth Century New York City,” Undergraduate Economic Review: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 8.

http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer/vol3/iss1/8

Oral History of the Korean “Comfort Women”, Columbia University http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/korea/comfort_women.pdf

Blackburn, George M., and Sherman L. Ricards. “The prostitutes and gamblers of Virginia City, Nevada: 1870.” Pacific Historical Review 48.2 (1979): 239-258

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3639274?seq=1/subjects

Fabiola Bailón Vásquez, 2017. “Reglamentarismo Y Prostitución En La Ciudad De México, 1865-1940.” Historias, n.º 93 (junio), 79-98.

https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/historias/article/view/10910

Revista Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña.

Carlos A Rodriguez Villanueva, “Amor licito e ilícito: un escape a los patrones amorosos establecidos [Historia socio-sexual en ella Caribe Hispanico, siglos XVIII-XIX: Cuba, Santo Domingo y Puerto Rico]”; Jose E Flores Ramos, “Vida cotidiana de la prostitutas en San Juan de Puerto Rico: 1890-1919”;

Nelly Vazquez Sortillo, “La violencia dentro de la violencia: un caso de violencia domestica en una hacienda esclavista en Puerto Rico (1871).”. 2006 vol 13, 2nd series. Issue downloadable from issuu.com

https://issuu.com/coleccionpuertorriquena/docs/segunda_serie_n__mero_13

348 Dra. Nieves de los Ángeles Vázquez Lazo “Historia de la prostitución en Puerto Rico, de 1876 a 1917.” Angel Collazo Schwarz, La Voz del Centro http://www.vozdelcentro.org/2009/08/23/la-historia-de-la-prostitucion-en-puerto-rico/ Podcast: http://www.vozdelcentro.org/mp3/Prog_348.mp3

Isabel Luberza Oppenheimer, ‘Isabel la Negra’, Madam & owner of Elizabeth’s Dancing Club, Ponce, PR. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabel_Luberza_Oppenheimer

Juan A Vera Mendez “Legalización de la Prostitución” (slide presentation has helpful overview on prostitution in PR)

https://studylib.es/doc/6024328/la-prostitución—universidad-interamericana-de-puerto-rico

“1970s New York City: The dangerous & gritty streets during a decade of decline.” NY Daily News. Photographs of NYC’s sex workers included.

https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/gritty-new-york-city-1970s-gallery-1.1318521

Books

Timothy J Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920. (1994)

Christine Stansell, City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 1789-1860. (1987)

Shirley Stewart, The World of Stephanie St. Clair, An Entrepreneur, Race Woman and Outlaw in Early Twentieth Century Harlem. Peter Lang Publishers, 2014.

LaShawn Harris, Sex Workers, Psychics and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy. U Illinois Press, 2016.

Shane White, Graham White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem Between the Wars. Harvard UP, 2010.

Karen Abbott, Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys and the Battle for America’s Soul. [Chicago] Random House, (2008).

Laura Briggs, Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science and US Imperialism in Puerto Rico, University California Press, (2002).

Eileen J Suarez Findlay, Imposing Decency: The politics of sexuality and race in Puerto Rico, 1870-1920. Duke UP (1999).

Donna J. Seifert, Elizabeth Barthold O’Brien, & Joseph Balicki, “Mary Ann’s First Class House: The Archaeology of a Capital Brothel.” Robert A Schmidt & Barbara L. Voss, Archaeologies of Sexuality. Routledge, (2000), 117-128.

Wild West Book Review: Jan McKell’s Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains UNM Press, 2009

https://www.historynet.com/wild-west-book-review-red-light-women.htm

Heather Branstetter, A Business Doing Pleasure: Selling Sex in the Silver Valley 1884-1991. Wallace, Idaho. (author blog)

https://abusinessdoingpleasure.com

Race & the Houses

https://abusinessdoingpleasure.com/2017/08/17/race-and-the-houses/

Files at the Shoshone County Sheriff’s Office

https://abusinessdoingpleasure.com/2014/10/02/aboutthescsofiles/

Reports

“Garden of Truth: the trafficking of Native Women in Minnesota.” Minnesota Indian Women Sexual Assault Coalition. Report (2011)

https://vawnet.org/material/garden-truth-prostitution-and-trafficking-native-women-minnesota

“Prostitution: A violent reality of homelessness” (2001) report

https://www.issuelab.org/resource/prostitution-a-violent-reality-of-homelessness.html

Historical resource

Medievalists.net list of posts on prostitution, various locations during the medieval period

http://www.medievalists.net/tag/prostitution/

Mapping

Hell’s Half Acre, 2017 [Victorian Los Angeles]

https://la.curbed.com/2017/11/17/16654292/history-prostitution-los-angeles

Selected Items from the Internet Archive, Archive.org items

Search results: simple search, prostitution yields 1400+ items

https://archive.org/search.php?query=subject%3A%22Prostitution%22

US Congress, House Committee on Interstate Commerce, Memorandum on white slave trade. 1909

https://archive.org/details/memoranduminrewh00unit/page/n6

Rosine Association, Reports and realities from the sketch-book of a manager of the Rosine Association, December 1855.

https://archive.org/details/reportsandreali00pagoog/page/n7

An ordinance relating to houses of ill fame and prostitution Salt Lake City, UT, 1877

https://archive.org/details/ordinancerelatin03salt

Special Collections

KC History Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library Results – 60 objects

https://kchistory.org/islandora/search/Prostitution%20?type=dismax

Annie Chambers, (1843-1945) 19 results

https://kchistory.org/islandora/search/Prostitution%20?type=dismax&islandora_solr_search_navigation=0&f%5B0%5D=kcpl_mods_local_subject_ms%3A%22Chambers%2C%5C%20Annie%22

Modern Pornography & Sex Work Collection, 1960-1990. University of South Florida

https://digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0050529/00001

CSUN, The Oldest Profession (Collections overview)

https://library.csun.edu/SCA/Peek-in-the-Stacks/prostitution

Dr Bonnie Bullough Collection, 1954-2000. CSUN, Oviatt Library, Special Collections

https://findingaids.csun.edu/archon/?p=collections/controlcard&id=445

Reverend Wendell M Miller Collection, 1928-1988.

Citizens independent Vice Investigating Committee (CIVIC) CSUN, Oviatt Library, Special Collections

http://findingaids.csun.edu/archon/?p=collections/controlcard&id=102

Prostitution Collection, 1834-1954., Five Colleges (MA)

http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss108.html

Prostitution at Brigham Young University, 1997

https://findingaid.lib.byu.edu/viewItem/FA%207/Series%2010/Subseries%204/6.10.5.6.2/

Minnie Fischer Cunningham Papers, Standard Statistics on Prostitution Syphilis & Gonorrhea (1919)

https://digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/p15195coll33/item/224

Guide to Shelley Bristol Papers UNLV

https://www.library.unlv.edu/speccol/finding-aids/MS-00398.pdf

The Real Rainbow Row, Charleston Hotel

College of Charleston, Special Collections

https://speccoll.cofc.edu/the-real-rainbow-row/charleston-hotel-200-meeting-street/

New Orleans

The Library of Congress’ page on Storyville has several special collections from New Orleans which I have included below.

Storyville: A resource guide to commercialized Vice in New Orleans. Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/rr/business/storyville/books.html

IAL COLLECTIONS

Storyville: a resource guide to sources about commercialized vice in historic New Orleans.

February 2018

Table of Contents

Overview

Selected Book Titles

Newspapers

Special Collections

LC Subject Headings

Archives of the City of New Orleans. New Orleans Public Library.

http://nutrias.org/~nopl/inv/synopsis/synopsis.htm

This includes ordinances related to prostitution.

Louisiana State Archives. Baton Rouge.

https://www.sos.la.gov/HistoricalResources/Pages/default.aspx

See Research Historical Records section.

Louisiana and Special Collections. Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

http://libguides.uno.edu/special

Includes the following collections: New Orleans Chamber of Commerce Records, MSS 66 and Josie Arlington Collection, MSS 270.

Louisiana Research Collection. Howard-Tilton Library, Tulane University.

http://larc.tulane.edu/

Search in the following collections:

Al Rose Collection, RG 606 : Although listed as a jazz archive, Storyville was the place to hear jazz musicians. Search: Prostitution.

Master Rolls, Battalion Washington Artillery: 1861-1865.

New Orleans Travelers’ Aid Society Papers, RG 365.

New Orleans Records. New Orleans City Archives, Louisiana Division New Orleans Public Library.

http://nutrias.org/spec/speclist.htm

This collection includes arrest records, arrest index, ‘Jewell’s Digest of the City Ordinances’, etc.

Note: this collection is also available on microfilm at the Library of Congress.

New Orleans. Ordinances, etc. Jewell’s Digest of the city ordinances, Rev. ed. New Orleans, 1887.

LC Call Number: Microfilm 21895 JS

LC Catalog record: 47035734

Williams Research Center. Historic New Orleans Collection.

https://www.hnoc.org/

Blue Books in the Williams Research Center’s collection, probably the largest extant, is available for research. View one of the digitized Blue Books here. Please contact the center for more information.

Last updated: 02/09/2018