If you’re doing Latinx genealogy tied to the Spanish empire, you’ll eventually hit a version of the Registro Civil, the Civil Register for births, deaths and marriages that keep track of the population. Depending on the country, these volumes of vital records begin in different years, and are incredible sources of information… depending on how well the person reporting the death knew the family.

Once you become more familiar with these volumes, you’ll notice shifts in the formatting as it goes from completely handwritten (for better or for worse) to progressively printed forms for entry. The forms evolve as the legal system evolves, with different requirements specified and vetted over time. Ok so stay with me– while this is an example from Puerto Rico, there’s a bigger lesson about details here for you to think about.

Variations, Forms, Changes…

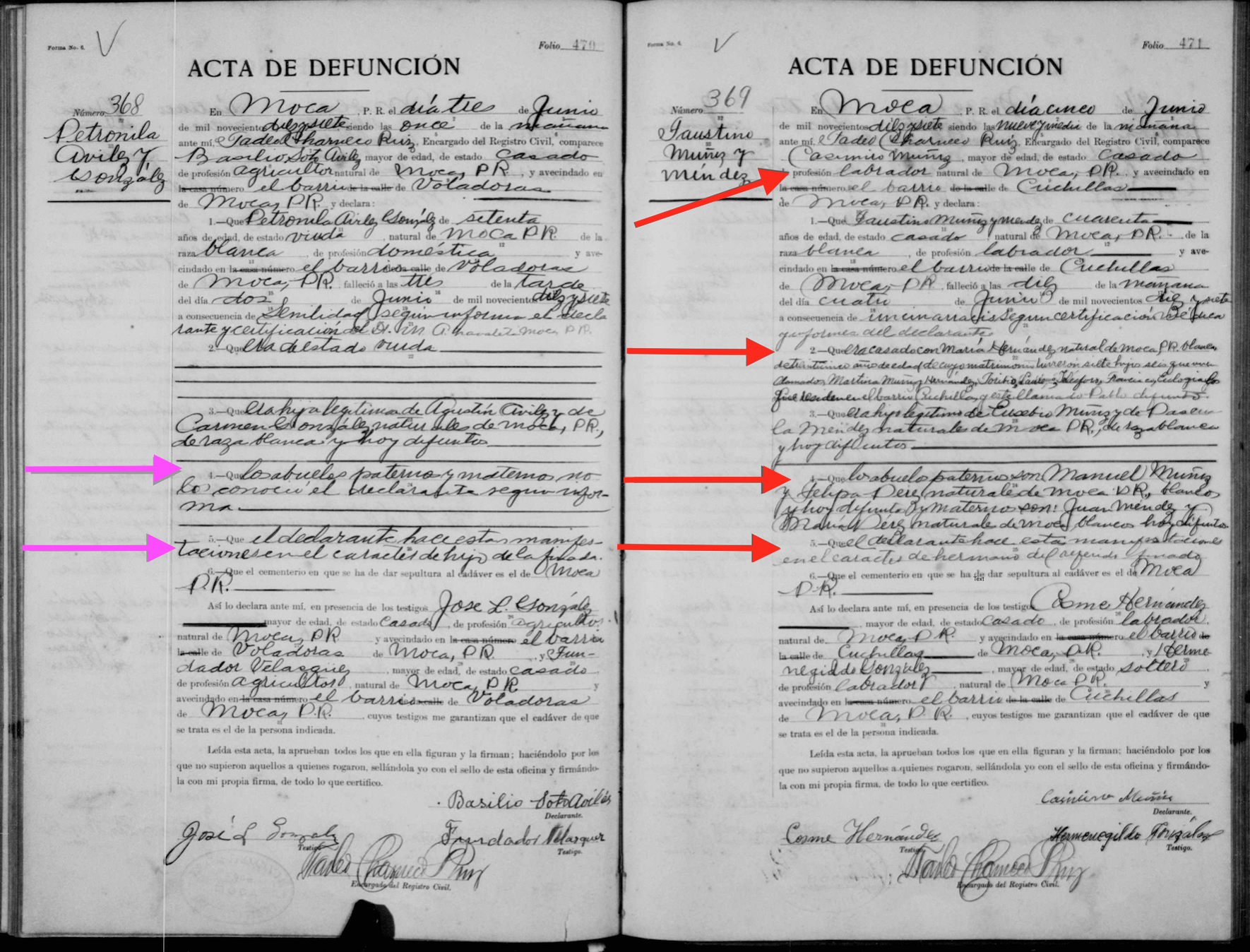

Recently, someone asked me about an ancestor tied to the Muniz line, and if you do genealogy, you know one person is never enough. So here’s an example of two 1917 death certificates, with significant differences in the information given by the Declarante (Informant). It’s a great example of the variations in registering information on life passages.

On the left, is the certificate for Petronila Aviles Gonzalez ( -1917), and on the right, Faustino Muniz Mendez (1877-1917). For Petronila, the informant is the child of the deceased. Basically her son, Basilio doesn’t know the names of his grandparents (pink arrows). For Faustino, the informant is a sibling of the deceased. His brother Casimiro knows the wife, her age, the names of their seven children and… and this is a big one, the names of his paternal and maternal grandparents.

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJD-NCNP

Details That Matter

In Petronila’s certificate, her son, Basilio Soto Aviles, is the informant, and his relationship comes later in the document. “Los abuelos paternos y maternos no lo conoce el declarante segun informa.” Translation: “As the informant states he doesn’t know the names of his paternal and maternal grandparents”

On the right, in Faustino Muniz Mendez’ certificate, his informant is his brother Casimiro Muniz. Casimiro is able to name Faustino’s wife, his seven children, his parents, his mother’s parents and his father’s parents. There are 16 people listed on his death certificate, and only 3 are listed in the transcription on FamilySearch. Good luck finding it by search- Muñiz is spelled Muñez.

In case you can’t read the image for Faustino’s certificate above, the red arrows point to significant information:

1. Casimiro Muniz mayor de edad, casado, de profesion labrador natural de Moca, PR y avecinado en el barrio de Cuchillas de Moca, PR…

2. Que era casado con Maria Hernandez, natural de Moca, blanca, de treinticinco anos de edad de cuyo matrimonio tuvieron siete hijos, seis que viven Amador, Martina Muniz y Hernandez, Toribio, Lauro, Telesforo, Francisco, Eulogio, los que residen en el barrio Cuchillas y este llamado Pablo difunto.

3. Que era hijo legitimo de Eusebio Muniz y Paula Mendez, hoy difuntos

4. Abuelos Paternos: Manuel Muniz y Felipa Perez, naturales de Moca blancos y hoy difuntos

Abuelos Maternos: Juan Mendez y Maria Perez, naturales de Moca, hoy difuntos

So we know how old his wife was, that they had some 7 children, one no longer living, and where his grandparents on both sides were from.

Benefits

It pays to go beyond the transcriptions on FamilySearch and Ancestry. That way you can avoid situations like having a parvulo (infant) listed in your tree as your great grandmother because you didn’t take the time to read the original document. Thanks to Casimiro’s statement, we have three generations on one document, and the information brings us closer to the early 1800s. Don’t take the notations for race literally, use it as a prompt to learn more about how people are categorized by official services.

- notice patterns in family names

- find different barrios (wards) that the family lived in

- determine an end date for grandparents based on mention of whether they are alive or have passed away

- another point of origin for your family, either on a local level or internationally

- you may also find unexpected details such as additional marriages or living arrangements, recognized or unrecognized children

Caveats

Most of this information is not transcribed on Ancestry or FamilySearch.

Not every certificate from the Registro Civil has this range of information, it varies by year, with some decades offering up more data than others.

Next for my Geneabuds…

Feel free to watch the upcoming episode #72 of Black ProGen LIVE with hosts Nicka Smith & True A. Lewis— coming up on Tuesday 13 November 2018: Life After Death: Getting More With Death Records – click here to watch live on YouTube. Tune in & discover the leads you can gather from obtaining, reviewing and distilling death records. I’ll be on the panel!

Hasta luego!

Discover more from Latino Genealogy & Beyond

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.