Jessie Walter Fewkes (1850-1930) was an American anthropologist, archaeologist and writer who worked in the Southwest US and the Caribbean.

I keep looking at Fewkes’ diary, parts of which read like a shopping list for Indigenous objects. Little has been written on his time in Puerto Rico, which was a result of the ‘demand for more scientific literature on Porto Rico and the West Indies’, which led to field work in the islands and publication of the Report on the Aborigines of Porto Rico and Neighboring Islands.’ [1]

Here’s an excerpt from Fewkes’ handwritten diary, from April 1904:

“A man ploughing a few days ago found a fine collar in his field

I was too late to get it as it had been given to Mr. Fritsche who will present it to a Berlin Museum-

Mr Trujillo of Ponce has a fine tripointed idol and a spherical bowl which he found at Guayanilla. Evidently then are many other things in the barrio called Indios when there was formerly an Indian settlement.

Nazario found many specimens in this region –“

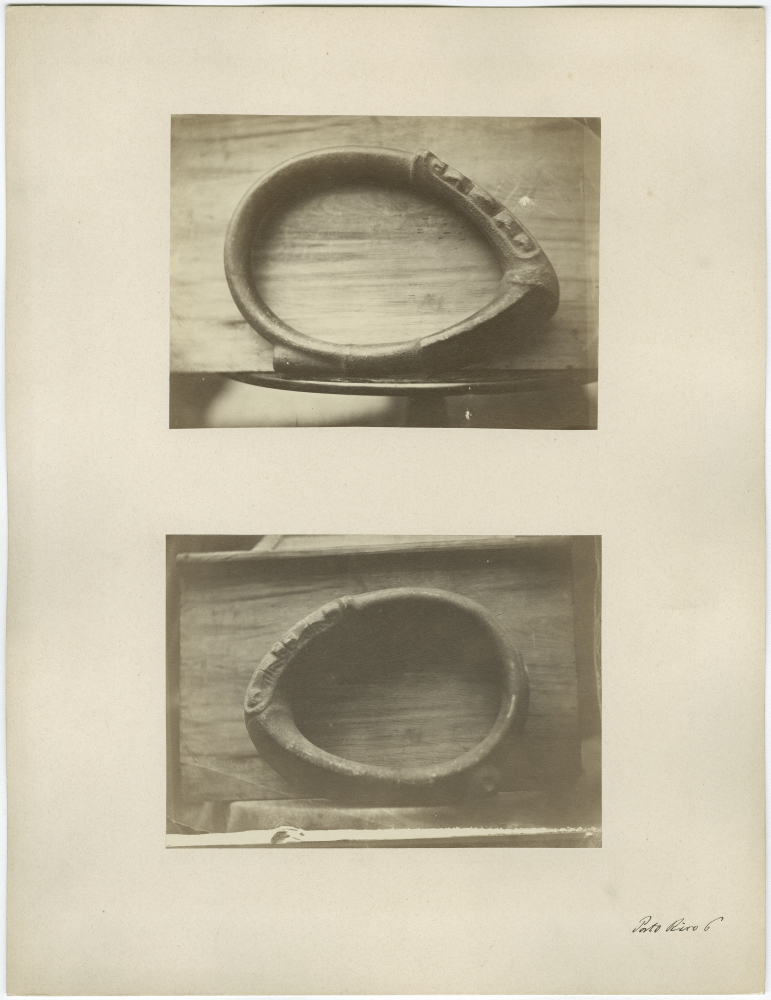

I couldn’t find more on Mr. Trujillo or Mr. Fritsche, but I did find the ‘Porto Rico 6’ photograph of a coa (also called a stone collar) whose accession date at the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum means it very likely entered the collection close to when it photographed by Adolf Bastian, before 1905. Given the timing, it’s likely the same artifact.

Barrio Indios, Guayanilla

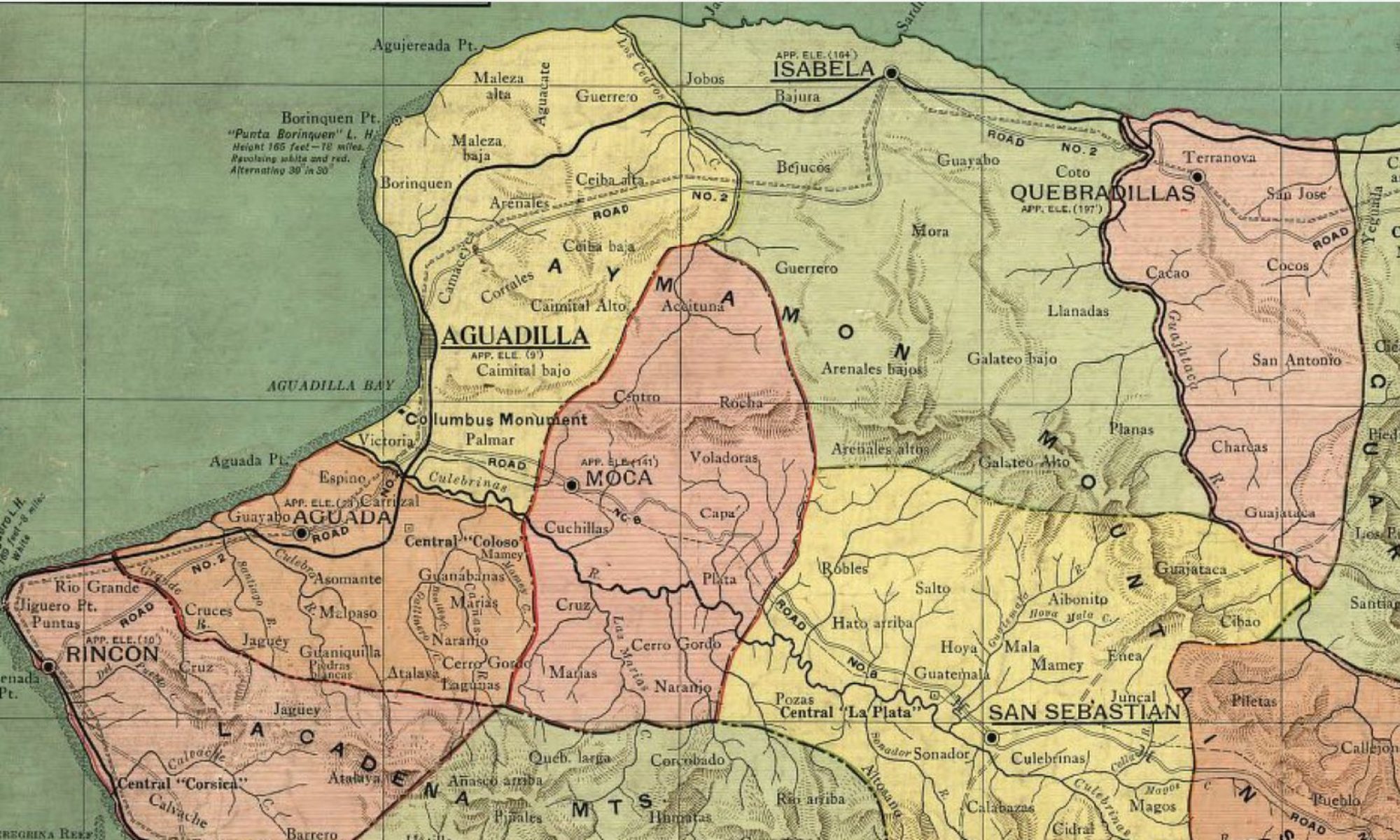

So, what about this settlement? As historian Rafael A. Torrech writes, Barrio Indios, Guayanilla, on the south of the island, is where the yukayeke of cacike Agueybana existed , where early wars of colonization took place. Eventually, sugar plantations covered the landscape and artifacts from ancestors emerged from the ground as it was prepared for planting. Collections were created by hacendados, and once the US had Puerto Rico as a colony, an international rush for artifacts intensified. Fewkes’ notebooks of his travels reveal a range of persons that he encountered while crossing the island from San Juan to Utuado, and then south to Ponce and the Indiera. Some people gift him objects like stone hatchets, buys others and inventories sites and the objects harvested from them.

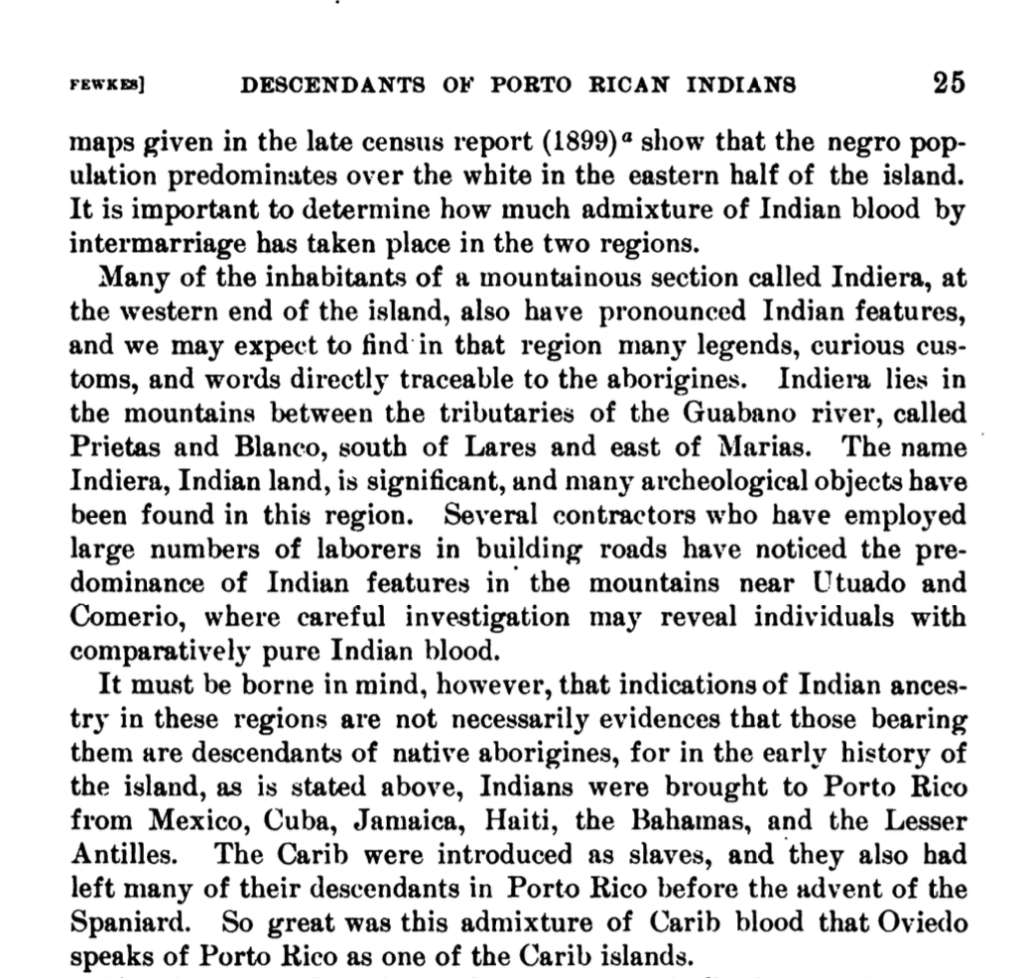

As stone objects turned up across the island, anthropologists and archaeologists began to surmise their age and purpose. Taino people were framed as outside of time although they are acknowledged and described as present in Fewkes’ essay. Looking back, he is evidently troubled by the complexity of AfroIndigenous identity. The idea of the ‘pure Indian’ colors his commentary, and oral history is suspect; notice that Natives are the laborers hired to build the roads in Utuado and Comerio; the area is even called Indiera. Fewkes goes on and acknowledges the presence of Indian ancestry, then the diversity of the Indigenous slave trade defeats the idea of any contemporary Taino identity on Boriken. No surprise really, as this is the heyday of Eugenic thought, which communicated and structured the spectacles of the World’s Fair and Expositions.

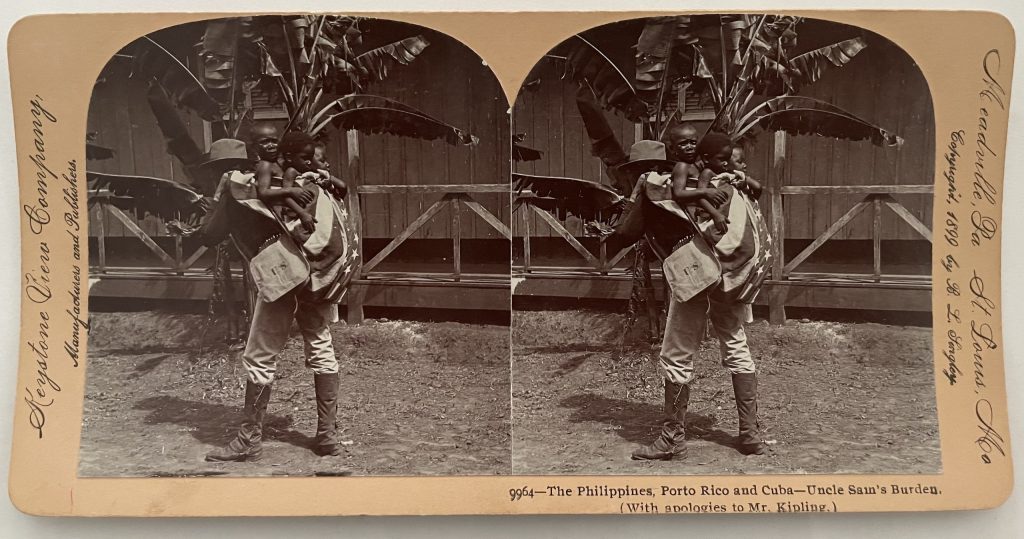

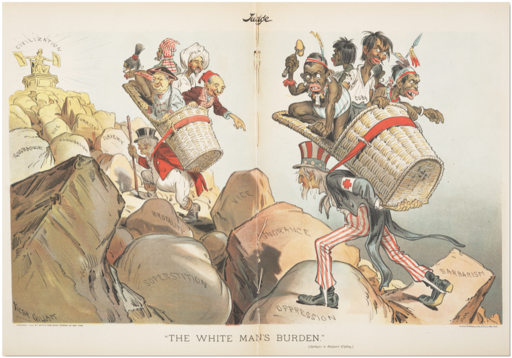

Envisioning Porto Rico, 1899-1904

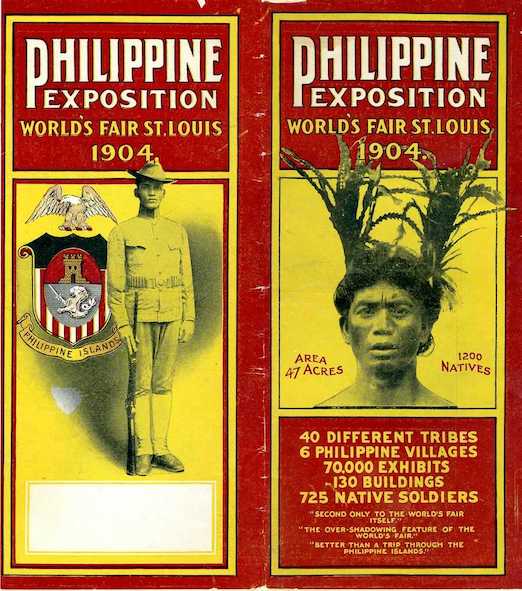

Here is an example of imperialist propaganda that circulated in the wake of the Spanish-American War that promoted the view of Indigenous people as incapable of self-governance and rule. Spain’s three colonies became US property. The Philippines, Puerto Rico and Cuba are here shown as 3 Black infants wrapped in a US flag on the back of a soldier who stands in for ‘Uncle Sam’. It’s a foto reenactment of the 1899 Victor Gilliam cartoon, “The White Man’s Burden” from Judge magazine. This anti-Native anti-Black perspective is part of the context for understanding the relationship of Native peoples to the US at the turn of the century, and at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition. Often the more offensive displays that underwrote white supremacy were in the entertainment areas of the fair, readily absorbed by millions under the rubric of ‘fun’.

Fewkes’ Reference to Father Nazario

In the 1870s, Father Jose Maria Nazario Cancel was brought by dona Juana Morales, a descendant of Agueybana to a cluster of some 800 stone pieces that she had protected over time. Today the archaeologist Reniel Rodriguez (UPR- Utuado) is researching the stones, and considers them as objects that date from precolumbian contact- 900BC-900AD. Yet the stones are not Taino and were not among those purchased by Fewkes in 1902-1903.

Not far from Guayanilla is the Centro Ceremonial Caguana, “the largest ceremonial site of its kind, not only in Puerto Rico, but the entire West Indies” built between 1200-1500 AD in the La Cordillera Central, the central mountain range. In terms of DNA testing, people from here, on the western side of the island tend towards higher percentages of Indigenous ancestry.

In terms of Caguana, it’s a ‘lived landscape’ a place where space, identity and heritage intersect and embodies group memory. It’s not static, but changes over time, and is “a locus for negotiating the dissonance between colonial and indigenous identities.” Despite years of neglect by the ICP (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriquena), it was a place vital for descendants to rediscover their cultural identity. Over five decades, Caguana has become a sacred site for Taino people, and in 2003-2005, the culture war between Taino activists and the ICP came to a head. (Diaz 232-233) Some still think Arawakan peoples, among them the Taino are extinct, and part of this thinking is the result of paper genocide.

The landscape in Puerto Rico is subject to constant disturbances from agriculture and development. The discovery of artifacts often means site destruction in order to avoid building delays as some have documented on video. There’s still much to learn from these archaeological sites, however for different audiences, namely Taino communities, the stakes are different. It’s about colonization and collections, and a difficult path to official recognition. It’s about seeing that connection between the past and present, learning what we can from these moments in colonization.

From ‘Elbow stone’ to Coa

As for the ‘elbow stone’ or ‘stone collar’ that Fewkes missed out on purchasing, this is called a coa, recognized as a sacred form by Taino peoples. It is based on the blending of two forms, the footrest of a hardwood digging stick for agriculture with that of the great serpent, whose head was carved into the foot rest. By bending the stick, using fire and water, the resulting form references the coiling of a snake and the form of human uterus, symbol of time and its passage as a spiral.

At some point, this wooden form was adapted into a stone carving with elements that reference the Taino worldview. You can read more about this on the Caney Circle webpage here.

1904: St. Louis Exposition

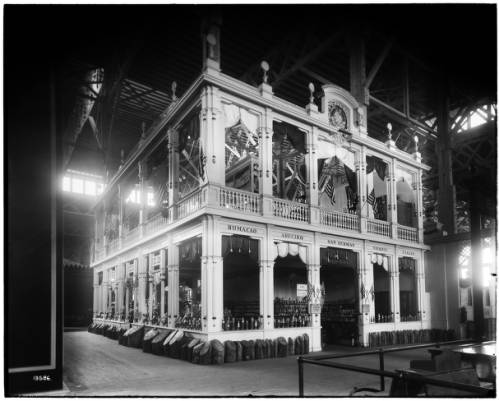

So what was some of the motivation for creating the collection? Fewkes brought together an assemblage of some 550 pieces of Indigenous / Arawakan stone artifacts exhibited at the 1904 St Louis Exposition. Our ancestors stone artifacts had a role at the fair, as a material assurance that primitive people were in the colonies. Here, representing ‘Porto Rico’ it suggests that Native people were extinct a part of something rapidly fading, a group no longer with us. How convenient.

The roofless building of Puerto Rico’s two floor ‘pagoda’ within the Agricultural Building is surrounded by props, sawed off barrel tops and angled logs in front to suggest trade, and tradition through the structure’s French detailing. The first floor “was dedicated to agriculture, mines, forestry and a few of the manufactures exhibits.” The second floor held “liberal arts and manufactures exhibits”, and a needlework display by the Women’s Aid Society, San Juan and the Benevolent Society, Ponce. The focus was on exports of coffee, sugar, tobacco, cotton, liquor and pharmaceutical products. The Puerto Rican legislature appropriated $30,000 for “the purpose of representation at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.” Yet it had no separate catalog, and no association with Fewkes’ collection.

I’ve searched collections for additional information on the stone artifacts at the Exposition, but the only mention of them is in Fewkes’ article in the Smithsonian papers. This collection wasn’t displayed here.

Consuming the Primitive

What grabbed attention at the 1904 fair was the display of Indigenous people brought from Africa and the Philippines. These were literally human zoos that several million people visited at St. Louis. They were subjected to perform as living examples of primitive people, yet the barbaric genocidal behaviors of the US go unmentioned. So, it seems stone objects of a supposedly extinct people were reassuring for the colonizer’s frame of reference.

Over 1200 persons were exported to the Exposition for display, including the Bedonkohe Apache leader and medicine man Goyathlay, known as Geronimo. While a prisoner of the US Government, he was exhibited at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha Nebraska, the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and at the 1905 inauguration of Theodore Roosevelt. He died imprisoned at Fort Sill in 1909. [3]

Collection, collection….

Where were the stones shown? I still haven’t found a precise location at the 1904 Exposition.

And after 1904, the collection of Arawakan stone objects left St. Louis and were returned to the bowels of the Smithsonian, where they were eventually put into their storage facilities. Back in 2004, I met Ricardo Alegria, QEPD, the Director of the ICP who told me he anticipated the day the objects at the Smithsonian would be repatriated to the island. At that time, I didn’t realize how different an idea of Nation would be for me today. One day, Taino people will have facilities ready for their welcome return.

Seneko kakona.

References

Biography and Bibliography of Jesse Walter Fewkes. (1850-1893). (Reprint of Walther Hough’s Biography, Biographical Memoirs, National Academy of Sciences, 1932. 232pp). https://ia800205.us.archive.org/27/items/biographybibliog00nichrich/biographybibliog00nichrich.pdf

Rafael A. Inocencio Torrech: “Según diversos historiadores, varios yucayeques taínos de importancia estaban ubicados en el área sur de Puerto Rico, incluyendo el del legendario Agueybaná. Reconocidos historiadores como Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo –contemporáneo a la temprana colonización– ubican la aldea de Agueybaná en la ribera del Río Coayuco (hoy Río Yauco), con una población estimada entre 1,000 y 5,000 habitantes. Fue en la boca del Río Coayuco, según el historiador Cayetano Coll y Toste, que las fuerzas de Ponce de León derrotaron por primera vez a los indígenas en la llamada rebelión de 1511. La ribera y la desembocadura de este río, hoy conocido como Río Yauco, es consistente con la localización actual del Barrio Indios. El Barrio Indios también nos legó la Biblioteca de Agueybaná: uno de los hallazgos arqueológicos más singulares y excepcionales del País…” Rafael A. Torrech Inocencio, Barrio Indios, Guayanilla. 80grados.net 21 Feb 2020. https://www.80grados.net/barrio-indios-guayanilla/

Jesse Walter Fewkes, “The aborigines of Porto Rico and neighboring islands.” Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution to the Secretary of the Smithsonian, 1903-1904. Washington DC: SI. (1907) 1-220. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbo1906smitfo

“Porto Rico” The Final Report on the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. 331-332.

“Caguana Site.” National Historic Landmark Nomination. http://npshistory.com/publications/nr-forms/pr/caguana-site.pdf

Caguana, Puerto Rico: Sacred Land. 2007. Sacred Land Film Project. https://sacredland.org/caguana-puerto-rico/

Rosalina Diaz, “El Grito de Caguana: Identity Conflict in Puerto Rico.” in Diane F. George & Bernice Kurchin, Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance: contexts for a brave new world. U Press of Florida, 2019, 229-250.

“Geronimo.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geronimo. Accessed 18 Mar 2000.

Human Zoos: The Invention of the Savage. Exhibition Pamphlet. ACHAC & Fondation Lilian Thuram: Paris, 2015: https://www.achac.com/zoos-humains/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/zh-en-brochure.pdf

“‘Living Exhibits’ at 1904 World’s Fair Revisited: Igorot Natives Recall Controversial Display of Their Ancestors”, 31 May 2004, NPR.org https://www.npr.org/2004/05/31/1909651/living-exhibits-at-1904-worlds-fair-revisited

Appendix: Writings of Jesse Walter Fewkes on the Caribbean

On Zemes from Santo Domingo. Am. Anthrop., vol. iv, no. 2, pp. 167-175, Washington, 1891.

Prehistoric Porto Rico. Address by the Vice President and Chairman of Section H, for 1901, at the Pittsburgh meeting of the Amer. Asso. Adv. Sci. Proc. Amer. Asso. Adv. Sci., vol. li, pp. 487-512, Pittsburg, 1902. Reprinted in Science, n. s. vol. xvi, no. 394, pp. 94-109, New York, 1902. Translated in Globus, Band Ixxxii, Nrs. 18 and 19, Braunschweig, 1902.

Prehistoric Porto Rican pictographs. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. v, no. 3, pp. 441-467, Lancaster, 1903.

Precolumbian West Indian amulets. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. v, no. 4, pp. 679-691, Lancaster, 1903.

Preliminary report on an archaeological trip to the West Indies. Smithson. Misc. Colls., Quarterly Issue, vol. 45, pp. 112-133, Washington, 1903. Reprinted in Sci. Amer. Suppl., vol. Ivii, pp. 23796-99, 23812-14, New York, June 18-25, 1904.

Porto Rico stone collars and tripointed idols. Smithson. Misc. Colls.

Porto Rican elbow-stones in the Heye Museum, with discussion of similar objects elsewhere. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. xv, no. 3. pp. 435-459, Lancaster, 1913. Reprinted as Cont. Heye Mus., vol. i. no. 4.

[Report on] Ethnological investigations in the West Indies. Explorations and Field-work of the Smithson. Inst, in 1912, Smithson. Misc. Colls., vol. 60, no. 30, pp. 32-33, Washington, 1913. lls., Quarterly Issue, vol. 47, pt. 2, pp. 163-186, Washington. 1904.

Prehistoric culture of Cuba. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. vi, no. 5, pp. 585-598, Lancaster, 1904.

The aborigines of Porto Rico and neighboring islands. Twenty-fifth Ann. Rept. Bur. Amer. Ethn., pp. 3-220, Washington, 1907.

Further notes on the archaeology of Porto Rico. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. x, no. 4, pp. 624-633, Lancaster, 1908.

An Antillean statuette, with notes on West Indian religious beliefs. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. xi, no. 3, pp. 348-358, Lancaster, 1909.

Relations of aboriginal culture and environment in the Lesser Antilles. Bull. Am. Geog. Soc, vol. xlvi, no. 9, pp. 662-678, New York, 1914. Reprinted as Cont. Heye. Mus., vol. i. No. 8.

A prehistoric stone collar from Porto Rico. Am. Anthrop., n. s. vol. xvi, no. 2, pp. 319-330, Lancaster, 1914.

[Report on] Antiquities of the West Indies. Explorations and Field-work of the Smithson. Inst, in 1913, Smithson. Misc. Colls., vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 58-61, Washington, 1914

Vanished races of the Caribbean. Abstract of paper read before the Anthrop. Soc. Washington, Nov. 3, 1914. Journ. Washington Acad. Sci., vol. v, no. 4, pp. 142-144, Baltimore, 1915.

Prehistoric cultural centers in the West Indies. Journ. Washington Acad. Sci., vol. v, no. 12, pp. 436-443, Baltimore, 1915.

Engraved celts from the Antilles. Cont. Heye Mus., vol. ii, no. 3, New York, 1915.

Archaeology of Barbados. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., vol. i, pp. 47-51, Baltimore, 1915.

Prehistoric island culture areas of America. Thirty-fourth Ann. Rept. Bur. Amer. Ethn., Washington, . [In press.]