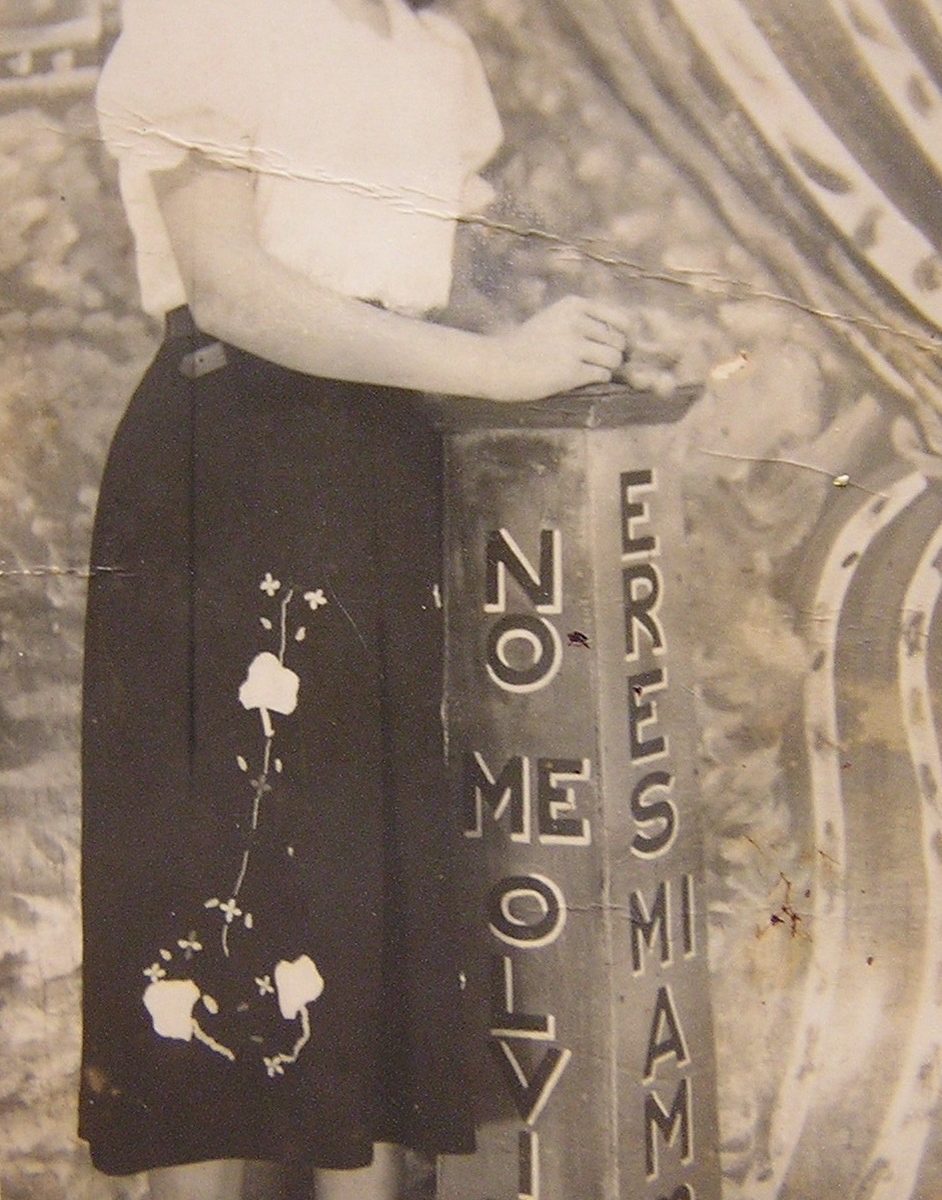

I was blessed to meet an elder generation of lacemakers— tejedoras or mundillistas–, before they passed on. I met many amazing people when I was involved with field research for my project, thanks to happening upon Ada Hernandez Vale in Jaime Babilonia’s Farmacia in the Plaza, the heart of Barrio Pueblo, Moca.

Ada was carrying her chihuahua, Trompito, and in Spanish asked me if I was looking for mundillo, which is handmade Puerto Rican bobbin lace. Actually, I was there following a burning genealogical mystery about some of the Babilonias in Barrio Pueblo, but her question stunned me. No, I answered, and added, I didn’t know what it was. She shot back, “how can you not know about mundillo if you’re from here? Come to my house, I’ll show you.”

My husband Tom and I walked a couple of blocks to her home just off the plaza. Over the next three hours, Ada proceeded to haul out work that i’ve never seen before. “This is mundillo, and my brother Mokay is opening a museum. I want you to meet him.” As with other families in Moca, members of the Hernandez Vale family were long involved in mundillo thanks to their mother, Julia Vale Mendez (1906-1991), as makers of telars, as lacemakers and brokers of encaje puertorriqueno. This led to Mokay (Benito) Hernandez Vale’s establishing el Museo del Mundillo on Calle Barbosa thanks to the support and efforts of a group of lacemakers who shared this vision.

Researching in Moca

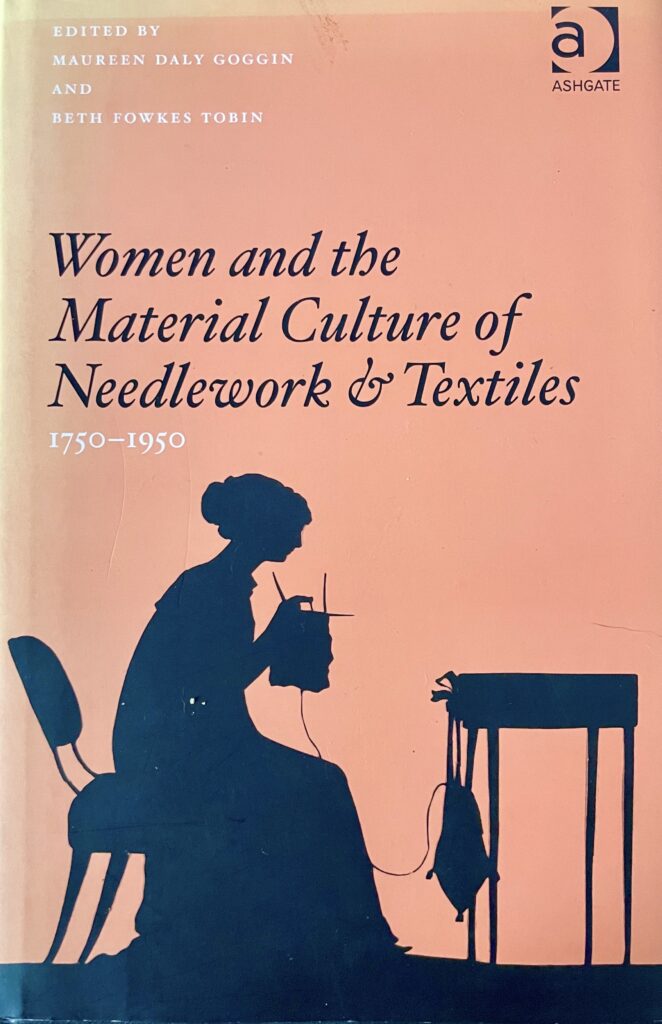

This is how my research began, a series of projects that tie together origins, trade networks, slavery and family histories. While this research culminated in a book chapter, “Mundillo and Identity” in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles (2009), there’s more left to do.

Mundillo is important, as the women who worked in the pueblo had a network of production and community that maintained relationships within and without the island. They produced lace that connected the sacred to the secular, that marked rites of passage through delicate edging and decoration that spanned generations.

Ser tejedora – to be a lacemaker was a skill set that held so many social and historical connections. The activity is visible in the 1910 Federal census and then spreads by subsequent census as young women learn the skill in school and from each other as the Industria de la Aguja begins to swell. Puerto Rico was the first maquiladora, and the history of mundillo falls on the edge of that history.

Literature on mundillo

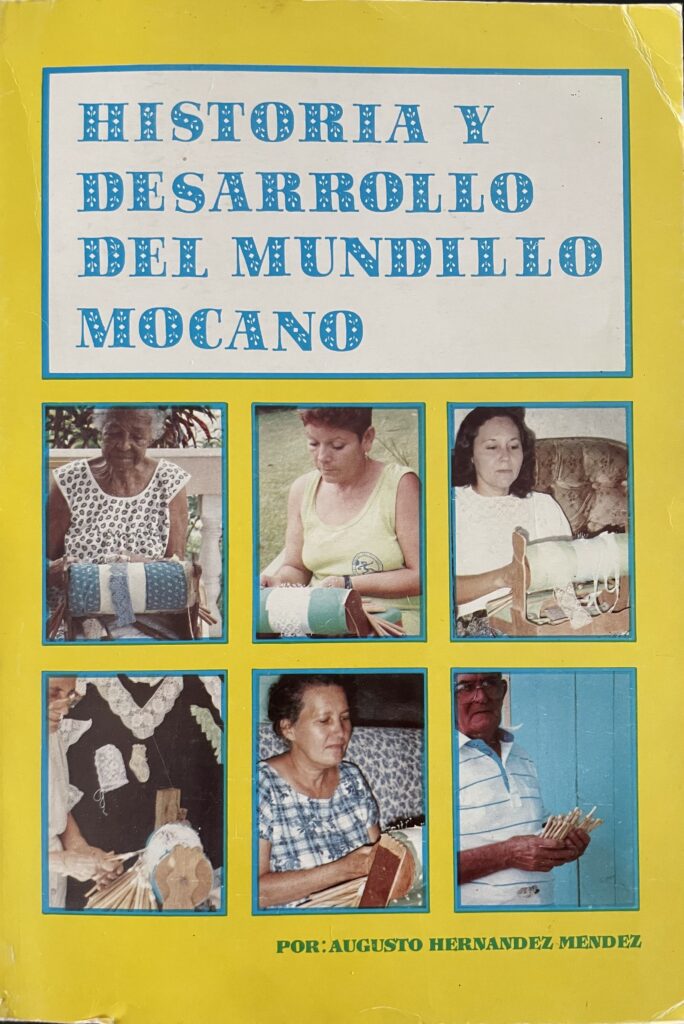

The first book on the history of mundillo is by Augusto Hernandez Mendez (QEPD), Historia y desarrollo del mundillo mocano. (Moca, 1993). He was an educator and administrator involved with literacy, and cultural celebrations, amplifying the efforts of many. What’s great about his book are Capitulo VI and VII, which covers the artisans who serve as ambassadors of the craft, and the artisans involved with producing the tools, patterns and lace in Moca. The mini-biography of each person is accompanied by a photograph.

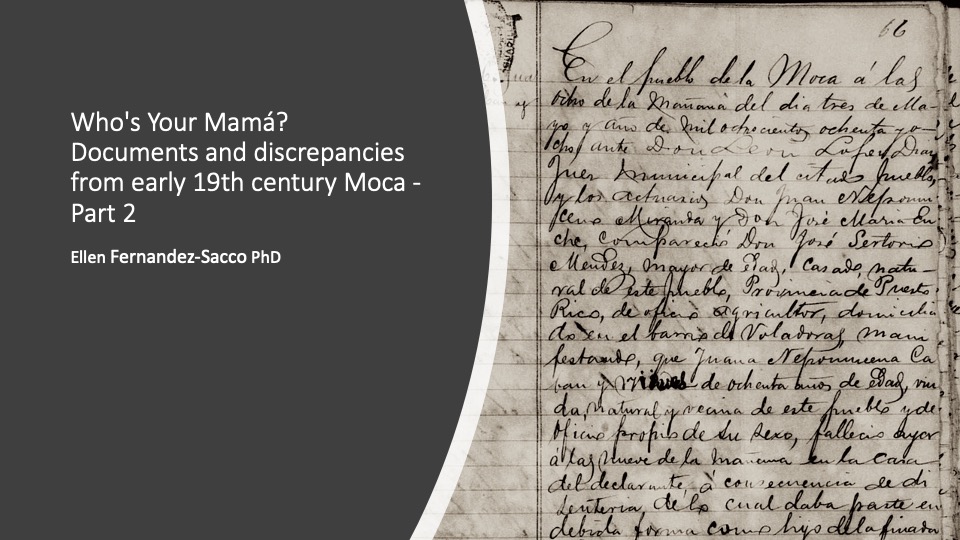

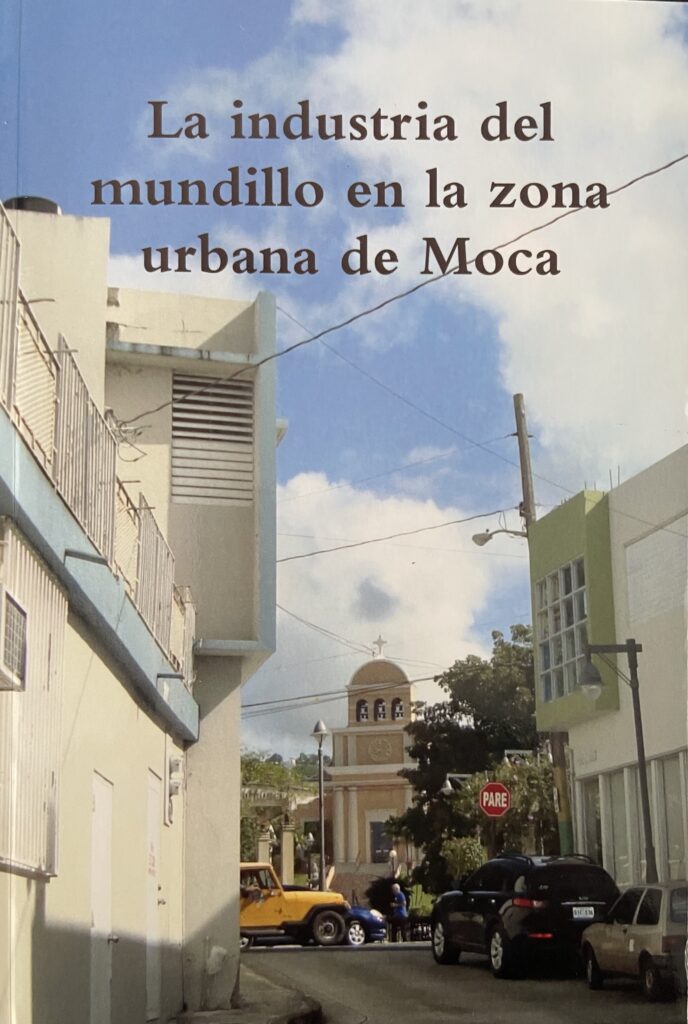

The second book is Antonio Nieves Mendez, ed. La industria del mundillo en la zona urbana de Moca: Reconocimiento general de las propiedades de la zona urbana de Moca asociada con el produccion del mundillo. (2011, Lulu.com) The study maps out the dissemination of mundillo within the town from 1885-1930. These books are incredible genealogical resources if you happen to have family from Moca, because of the focus on women artisans and teachers.

My contribution to this literature is “Mundillo and Identity: The Revival and Transformation of Handmade Lace in Puerto Rico” in Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin’s Women and the Material Culture of Needlework. (Ashgate 2009) This chapter on the development of mundillo provides a larger historical perspective. By tracing the practice as global one, it shows mundillo’s spread on the island was tied to school training in the 1930s. This left mundillo as an adjunct to the activity of the Industria de la aguja, the Garment Industry, which provided piecework to thousands of women across the island.

Las Tejedoras: Algunas artesanas de Moca

Olga Hernandez Rivera stands among the expert tejedoras of Moca. Her husband is a artisan in wood, who makes a range of elegant telars, the base for working lace with bollillos. With roots in barrios Cerro Gordo and Centro, Olga has lived in Barrio Cuchillas for decades with her family. When I visited Moca some years ago, Olga introduced me to other mundillistas and showed examples of her work. She told me about one of her teachers, Andrea Lopez Rivera (1928-2003), who did much to teach mundillo to women in Moca through the Servicio Extension Agricola.

The death of Virginia Rodriguez Arocho brought the tejedoras in the community connected to el Museo de Mundillo out in remembrance of her at her wake. Nelly Vera Sanchez is among the lacemakers recognized by major cultural organizations and was named a National Heritage Fellow by the Endowment for the Humanities in 2021. Yolanda Romero Aviles is an accomplished tejedora, Among the items that she creates are lace covers that edge the lower sleeves of judicial robes. These areas of mundillo add contrast and do not detract from the robe as a symbol of the court. By wearing mundillo, one communicates knowledge of local tradition and cultural pride. Romero Aviles’ sleeve covers are extensive– about 6″ in width. Her works feature advanced techniques in bobbin lace to create a ground interspersed with floral and abstract motifs.

Magda Rivera kindly showed me her shop, which features a memorial to her mother, the tejedora Julia Bosques Torres (1911-1992), who learned to make lace at age 8. In 1940, she established a shop in her home for buying and selling lace and other items that she ran until her death. (Hernandez Mendez, p108)

Maria C. Guadalupe made lengths of lace along with a range of amazing small gifts to children and adult’s clothing. These works are embellished with edgings and panels of mundillo and delicate embroidery, as in this dress below:

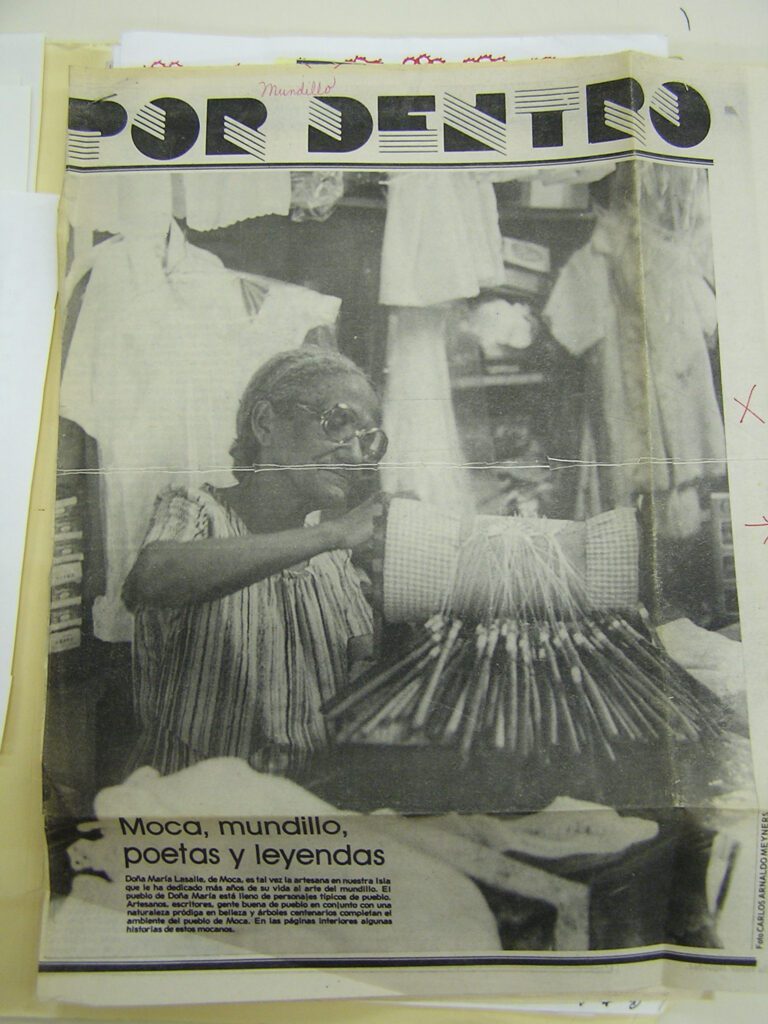

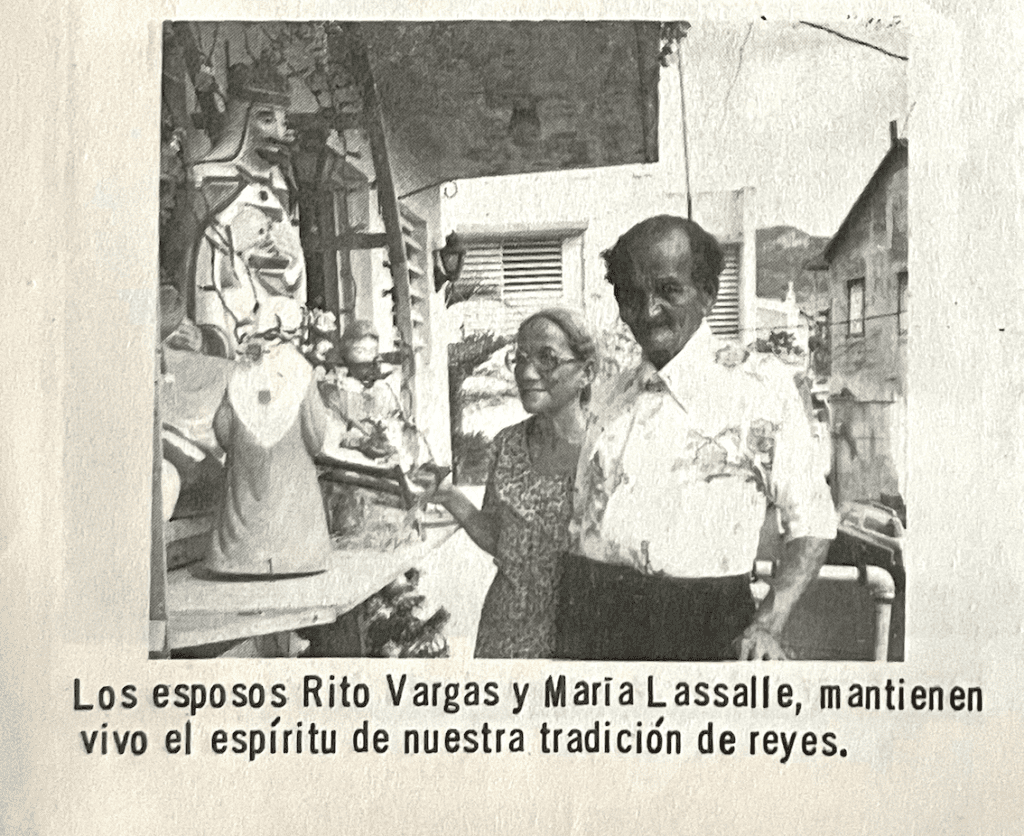

Although there were a number of women who practiced mundillo in Moca, a smaller number achieved fame for their work and their shops, as did Dona Maria Lasalle (1914-1913). The mundillo she is working on is an old model that predates foam– that narrowing of the center of the upper armature happens with the banana leaf stuffing of earlier years. Still it holds its complex pattern using dozens of bollilos (bobbins).

She was married to Rito Vargas Gonzalez, a carpenter, furniture maker and friend to my grandfather, Alcides Babilonia Lopez, together they kept the tradition of el Velorio de los Reyes celebrated in Barrio Pueblo still held today. Their son Rito Vargas Lasalle continues to promote their memory.

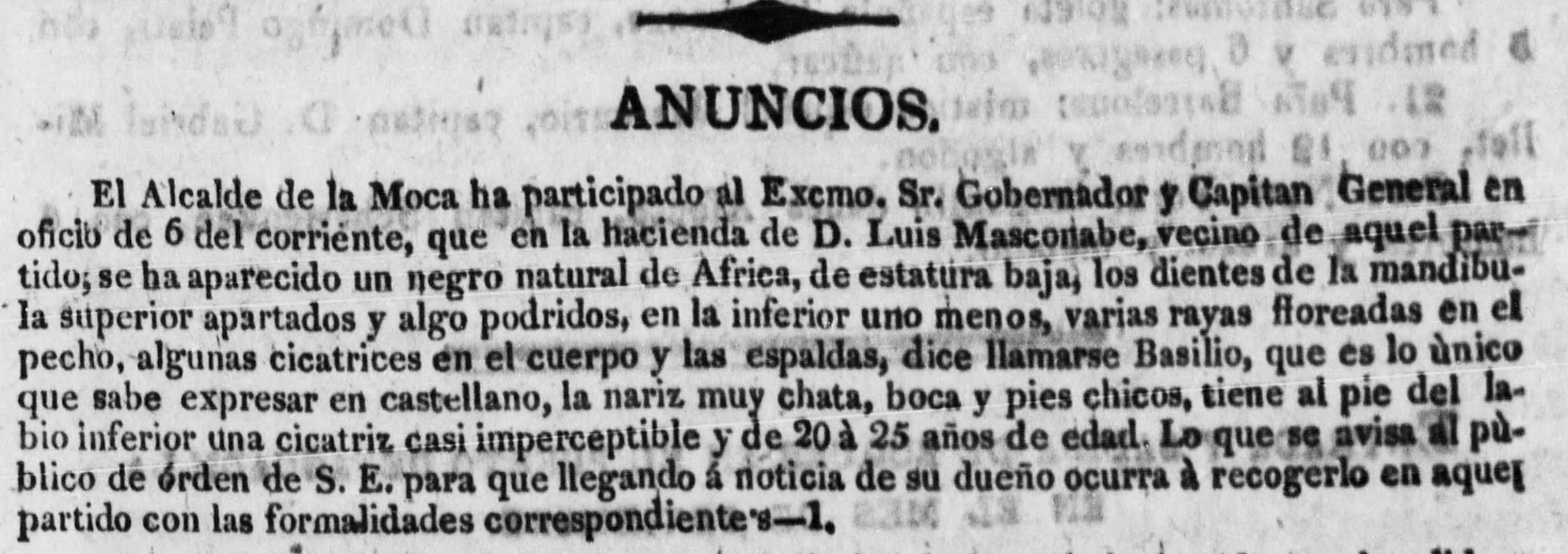

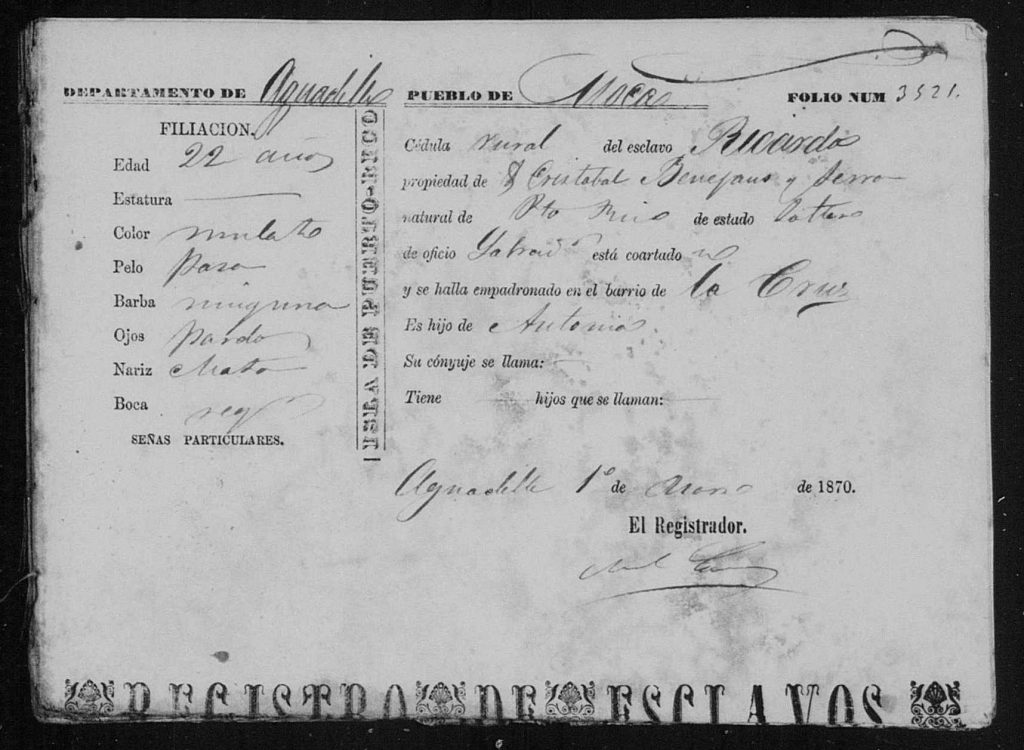

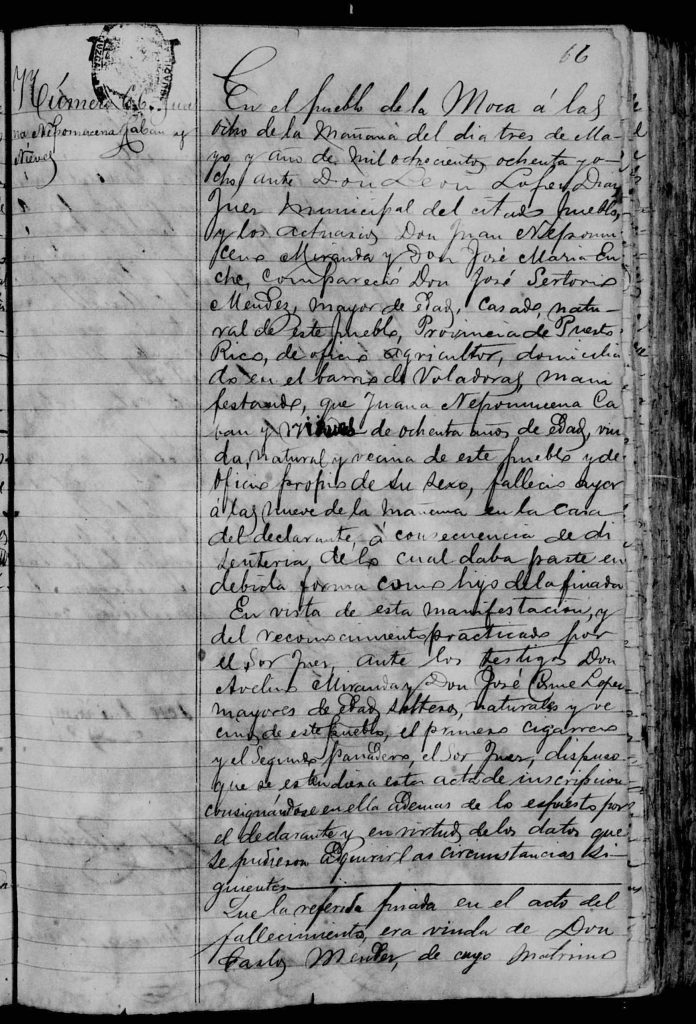

Maria Lasalle was cousin to Virginia Arocho Rodriguez, whose mother Juana Rodriguez Lasalle and grandmother Dionicia Leoncia Lasalle gave the account of their enslavement to the historian Luis Diaz Soler in 1945.

There’s much to the history of mundillo, and I am fascinated by how it interconnects its practitioners, its exhibitors and its wearers. Looking forward to sharing more about people connected to mundillo.