So happy to share that “Not Yet Completely Free: Gradual Emancipation and the Family of Moses Williams, Philadelphia 1776-1833. ” is in the latest issue of the AAHGS Journal!

Volume 43 Winter Edition of the AAHGS Journal is available via Amazon. Editor Guy Oreido Weston brought together articles that span several states. The issue delves into family and local histories, the recovery and reclamation of Black cemeteries in Washington DC and New York.

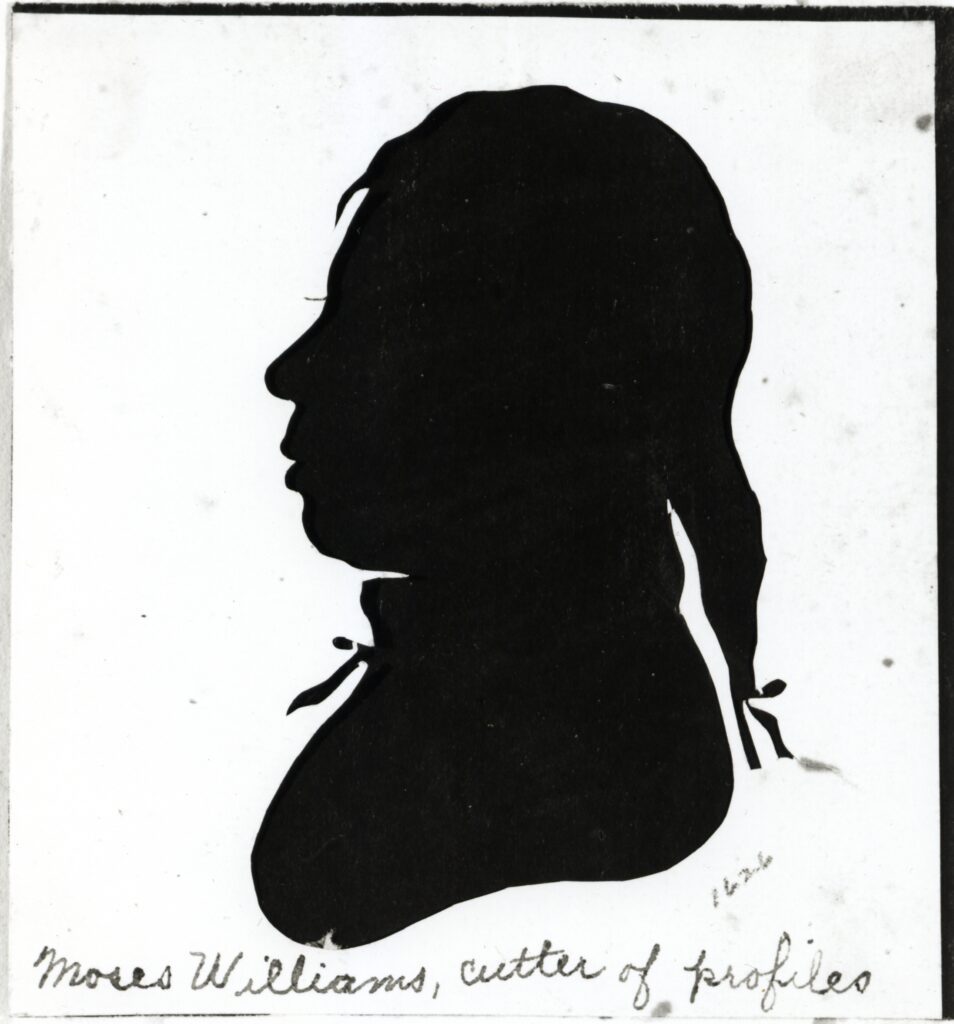

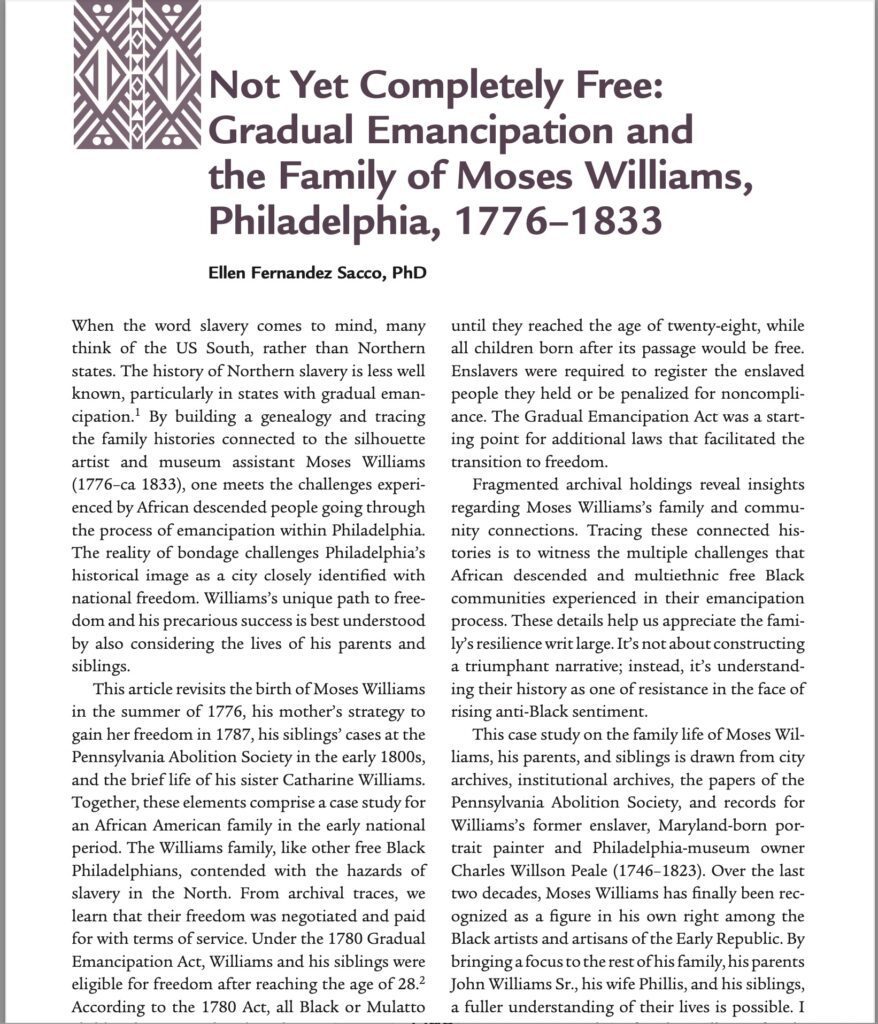

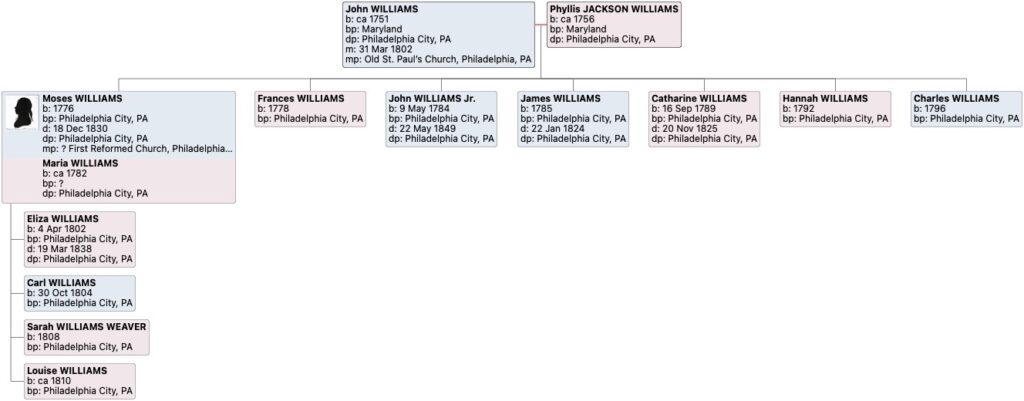

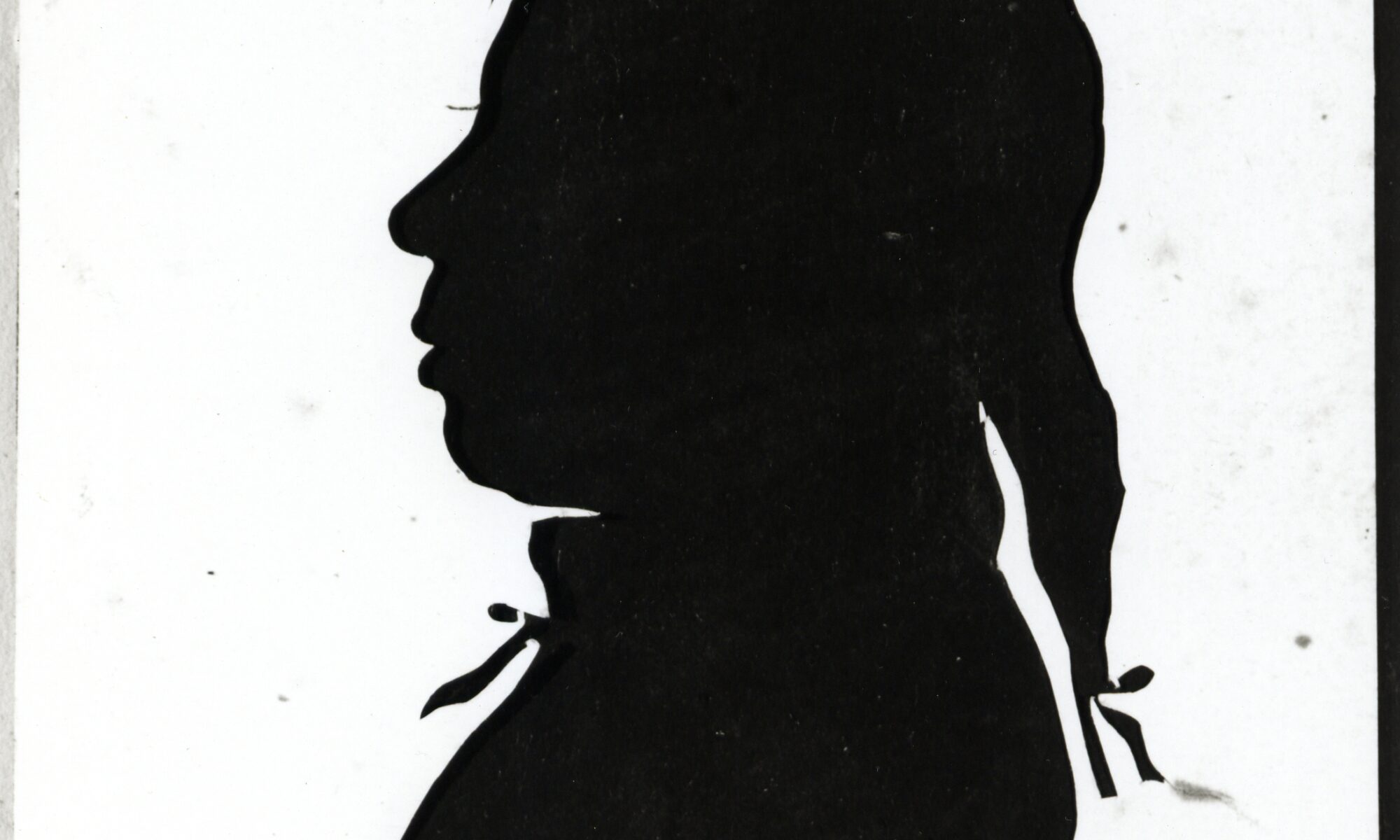

Moses Williams is a paradigmatic figure for the 250th Anniversary of the founding of our country. Born into slavery in 1776, and eventually freed by 1803 under the terms of the 1780 Gradual Emancipation Act, Williams was the first Black museum professional. For a time, he owned property and a house at 10 Sterling Alley; he had a wife and at least four children. Raised in the museum, in proximity to the Peale children, Williams learned how to read, how to prepare birds and other animals for displays. Eventually he cut silhouettes there using a patented machine. In 1810, he considered his role important enough to tell the census enumerator that he ‘attended at the Museum’.

Now in 2025, an amazing group of historians, curators, writers and artists from different institutions & independent professionals are focusing on Williams’ life and craft. This is a sea change from the shock I experienced listening to an exasperated curator ask why look at him? in the midst of the Peale exhibition touring nationally some two decades ago. I published my first article in Museum Anthropology detailing what I learned about Williams, who also figured in my dissertation. This built on then-current Peale scholarship on the audience for Peale’s Museum. Black history did not figure into the history of museums, even though to function, some institutions were dependent on the labor of enslaved and indentured persons. Similar to Monticello, the Peale project suffered from a segregated history that has changed since the late 1990s.

Since then, Williams has been recognized as an artist and artisan in his own right, part of a growing community through exhibitions organized by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw and other scholars. There is also an initiative by Faye Anderson, Director of All That Philly Jazz; she also serves on the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and plans to have him remembered with a historical marker where his former home stood, to be featured in future walking tours of the city.

Thanks to Nancy Proctor’s leadership at The Peale Baltimore’s Community Museum, much is done to anchor Williams’ memory into the 21st century– through the Accomplished Arts Apprenticeship Program and the creation of a Moses Williams exhibit at the museum. All of these projects do not just focus in on Williams, but intersects with community, provide spaces for connecting to the fabric of historic Philadelphia and present day Baltimore.

Williams is a historical figure I can relate to. He knew a lot about many things, was literate and skilled with his hands. When I went to museums I found myself connecting to the people who worked there cleaning, protecting and maintaining the collections, and so I see him as a kindred spirit, an ancestor who deserves to be taken seriously. To see the constructed nature of the display, its arrangement, the acquisitions taken as booty in wartime, silenced behind display labels shows the larger threads that colonization wove to establish particular kinds of truth. There was a silencing or veiling of the destruction of Native settlements and the genocide that accompanied these early campaigns, also tied to an economy built on the backs of enslaved people. Despite these challenges, Williams’ presence is there, part of a larger story of this nation.

Beyond the display were questions of family. Even with what was reconstructed and recently discovered, there remain questions and the hope of finding more fragments to pull together. I’m part of a group that shares these new finds. Public historian Dean Krimmel working with The Peale found a probate file showing that he died 18 December 1830; of three daughters, two, Louise and Sarah are named, his son Carl became Charles. Now we know he had four children with Maria– whose surname remains unknown. The likelihood of finding descendants today increases with these additional names.

But back to Williams and his family. Their experiences resonate, as they lived under the threat of kidnapping and forced deportation, the result of the constitutional amendment passed in 1793– the Fugitive Slave Act. They did everything to insure their family’s survival, even if that meant separation by indenture. My research uses details from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers, church records, the Peale Papers, newspaper accounts, census records and other items to reconstruct two generations of the Williams family. My hope is that this reconstruction makes it possible for descendants to connect.

Hope, resilience and faith in a better future drove their choices. To face the future despite the challenges is what defines the Williams’ family history.

May the ancestors rest in power.

Discover more from Latino Genealogy & Beyond

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Reply to “Moses Williams: The First Black Museum Professional”